Who is Octavius Catto? Learning about Philly’s first public monument to an African-American

Listen 4:28

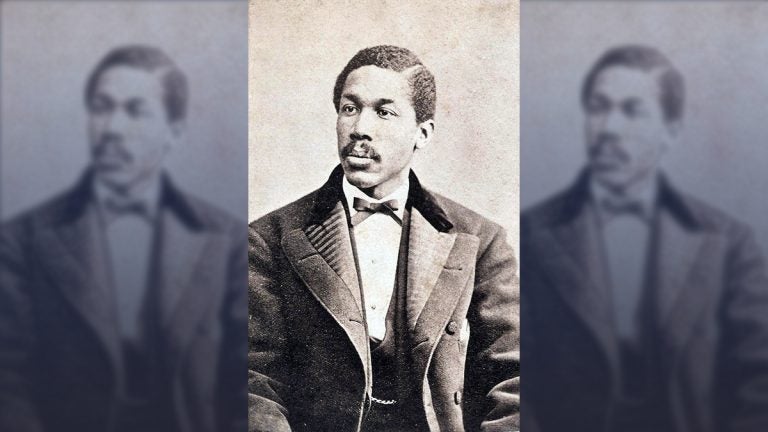

Octavius Catto (Wikimeda commons)

Every morning, I take the 33 bus to work. And for the past few months, I’ve noticed something looks different.As the bus makes its wide turn around City Hall onto East Penn Square, I see five tall pillars draped in white tarp. The pillars are fenced in. Tied to that fence is a banner that reads, “Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund.”

The banner features a portrait of a dapper black man with a handkerchief in his left breast pocket. His hair is parted, he has a thick mustache, and he’s actually quite attractive.

I turn to the woman sitting next to me, Anna D’Shields, and ask her if she knows who this man is. She whispers, “No.” But she pulls a small notebook out of her purse and asks me to spell his name.

Teacher, activist, civil rights leader

So, who was Octavius Catto?

To find out, I turned to former Philadelphia Inquirer reporters Dan Biddle and Murray Dubin who co-wrote the book “Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America.”

“A teacher, a great baseball player, an orator, a civil rights leader, an activist,” said Biddle, listing just some of Catto’s accomplishments.

The effort to erect the statue started with Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney. As a city councilman, he helped establish the Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund; today, he has a portrait of Catto hanging in his office at City Hall.

During an interview with WURD radio last year, Kenney was asked why he, as an Irish Catholic, is so infatuated with Catto’s story.

“Because an Irish Catholic killed him,” he said. “I feel like somehow me being a part of this is me righting that wrong.”

In the mid-19th century, Philadelphia had one of the largest black populations in the U.S. — many of them the children of former slaves. But they were still denied basic civil rights, and racial tensions between blacks and the Irish were high.

Catto and his 22-year-old fiancee, Caroline Le Count, were among a group of young political activists who emerged at this volatile time in the city’s history.

Together, they successfully integrated the city’s streetcars, 90 years before Rosa Parks sat down on the bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

Catto also worked hard to get black voters to the polls.

Then, on Election Day 1871, Catto was doing just that when an Irish political operative named Frank Kelly shot him multiple times on South Street.

Catto was dead at 32. Kelly was later acquitted by an all-white jury.

Catto’s story went largely untold for more than 100 years after his death.

“Black leaders in the 19th century, with the exception of Frederick Douglass, which is the only name people recognized, have been shortchanged …,” Dubin said. “They were not writing the history books, and no one was writing about them until the last 20 or 30 years.”

But Catto’s family kept records of his life. Leonard Smith, one of Catto’s descendants, said the family moved to New Jersey after his ancestor’s death. And generations later, while family members were sitting around at the dinner table or on the porch, Catto’s name would surely come up.

A teaching moment

As my bus slowly creeps through the traffic to the other side of City Hall, I can see the statue of former mayor and police commissioner Frank Rizzo.

The national conversation about monuments in the wake of deadly events in Charlottesville, Virginia, has reignited a debate in Philadelphia about whether Rizzo’s statue should be removed from its place outside the Municipal Services Building because of his record of police brutality — especially in communities of color.

That debate has highlighted the fact that of Philadelphia’s more than 17,000 statues on public land, none are of African-Americans. That’s about to change.

When Catto’s statue is unveiled Tuesday morning, Smith plans to be there — and the significance of the moment isn’t lost on him.

“Especially in this time in history when they’re tearing down all the Confederate statues and actually putting up a memorial to a great African-American leader,” Smith said.

“Hopefully it will be a beginning of people recognizing that civil rights didn’t start in the 1960s … In fact, civil rights has been an ongoing struggle throughout African-Americans’ tenure in this country.”

Now, Smith hopes Catto’s 12-foot bronze statue can become a teaching moment for anyone who walks or rides by on the bus.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.