Trump is driving Philly’s Black immigrants to vote like never before

Trump called Haiti and African nations ‘shithole countries’ and made immigrants a public enemy. Philadelphia’s Black immigrants say they are motivated to vote him out.

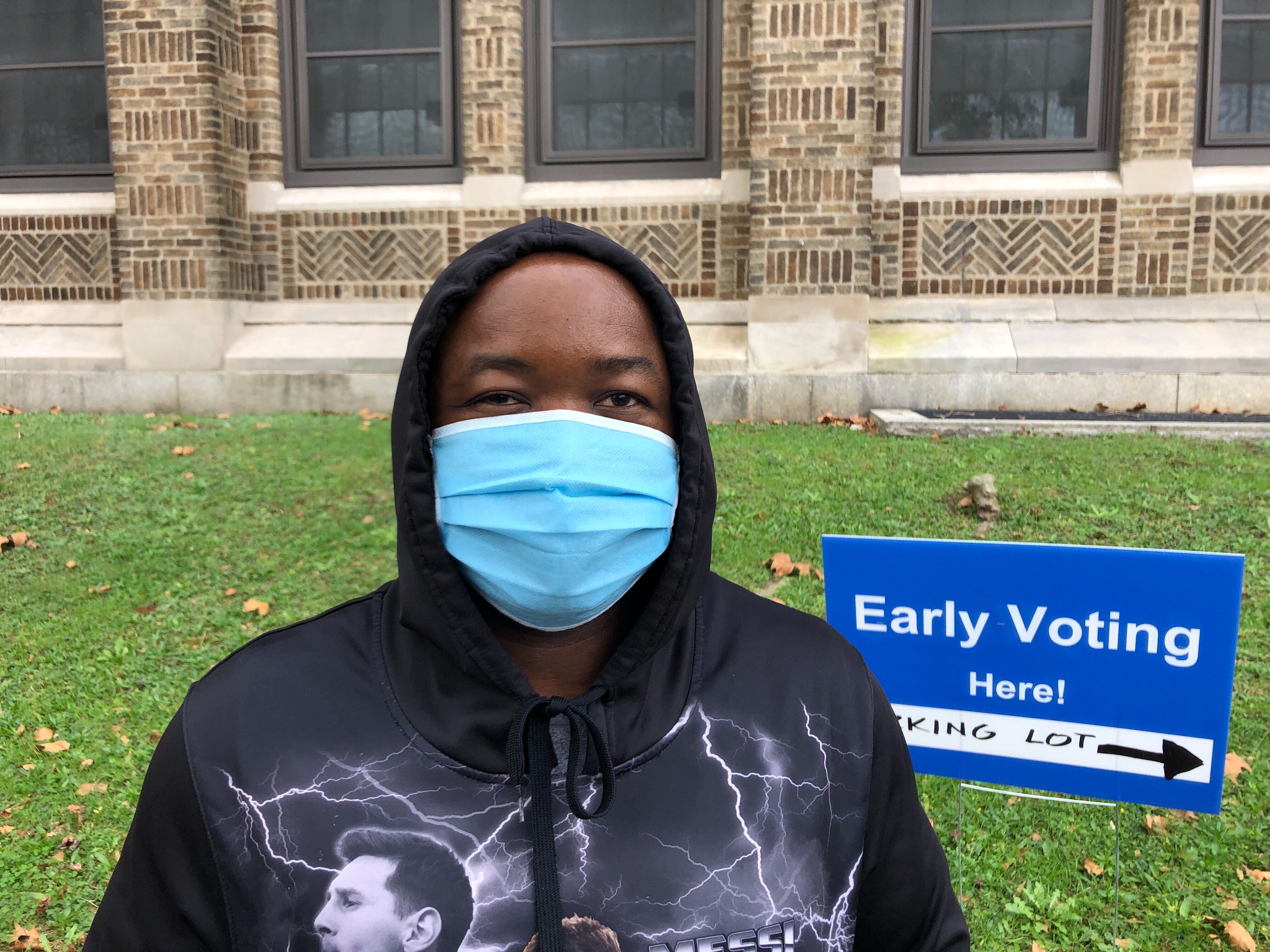

Satte Hoffe at her store in West Philadelphia. She’s a Liberian immigrant who said she’s voting because she fears a civil war. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Ask us: What do you want to know about voting and the 2020 election?

Like more than half of all registered voters in his Southwest Philadelphia precinct, Aruna Jaward stayed home on Election Day in 2016.

“I mean, I would have voted for Clinton if I made the efforts to register,” Jaward said. “But I didn’t do that.”

His decision wasn’t uncommon in his neighborhood, the center of Philadelphia’s African immigrant community — his 11th electoral district had one of the lowest rates of voter turnout in the city that year.

But things change. Last Sunday, the 37-year-old spent two and a half hours shivering in line to cast a mail-in ballot for Joe Biden and down-ticket Democrats. For Jaward, who immigrated to Philadelphia from Sierra Leone in 1997, the tipping point was Trump’s increasingly restrictive immigration policies.

These hit home for the recreational therapist two years ago, when his uncle was abruptly deported.

“It’s hard to see him back in Sierra Leone without nothing, struggling,” he said, as he waited in a snaking line to vote. “Decisions like that kind of motivated me to be here today.”

Organizers say there may be many voters like Jaward in Southwest Philadelphia’s Black immigrant communities, home to thousands from Caribbean nations and countries across Africa — primarily Liberia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria and Ethiopia. Voffee Jabateh, CEO of the African Cultural Alliance of North America, a nonprofit that helps eligible African immigrants gain citizenship, has seen the trend play out. He says those that are eligible to vote in Philadelphia — his group estimates there are 20,000 to 30,000 in the city — are increasingly driven by personal experience with Trump’s restrictive immigration policies.

“Pre-Trump, there was apathy,” Jabateh said. “Africa was called ‘shithole countries’ by this president. That brought a lot of attention to the Africans who are qualified to vote.”

Jabateh said others see echoes of the political fraying and national division that led to strife in places like his home country of Liberia, which was ripped apart by civil war twice in the past 40 years.

“Voting is a serious matter from where we come,” he said. “If the wrong leader is in place it can trigger a civil war.”

‘We kept our area organized and structured’

Four years ago, just 48% of registered voters cast a ballot in the 40th Ward’s 11th Precinct, a sliver of West Philadelphia lined with brightly-colored African grocery stores and restaurants.

In the 2016 presidential election, 66% of registered voters in Philadelphia voted, but there were big swings in different wards across the city. In student-heavy areas and certain low-income neighborhoods, turnout was 45%. In more affluent areas like Chestnut Hill or parts of Fox Chase, more than 75% of registered voters turned out. In Roxborough’s 21st Ward, one precinct that almost entirely encompasses Cathedral Village, a private retirement community, saw more than 86% of residents vote in 2016 — higher than anywhere else in the city.

A PlanPhilly analysis shows large swaths of North Philadelphia saw similar levels of voter turnout as the 11th Precinct, which is bound by 65th and 70th Streets, Woodland Avenue and a rail line. Other areas with less than 50% turnout include Overbrook and University City sections of West Philadelphia. While University City’s low turnout is likely driven by a large and transient student population, the other areas share a different characteristic: high rates of poverty.

Higher poverty rates have long been correlated to lower rates of voter turnout. People living in poverty may not see an upside to taking part in a political process that often ignores their most pressing concerns. Others may be interested in politics, but struggle to learn about the process or find the time to cast a ballot as lines pile up at certain polling places.

In a census tract where 38% of families live under the federal poverty line, Jabateh thinks a combination of these factors led Southwest Philadelphia’s African voters to cast fewer ballots in 2016.

“Those who are poor tend to have less enthusiasm for voting,” he said.

His group is trying to push back. In the last few weeks, ACANA mounted a social media campaign at getting Africans to vote and launched a door-knocking campaign in the days leading up to the election to make sure registered voters get to the polls.

There are signs the work is paying off. Residents like Satte Hoff, who owns Satte African Food and Fashion on the 6600 block of Woodland Avenue, said she registered to vote for the first time this year because of her frustration with Trump. Hoff immigrated from Liberia in 2004, and her sister has long made annual visits to see her. That changed four years ago.

“Since Donald Trump became in power, she never get [the visa],” said Hoff, 57.

Hoff said she knows dozens of other African immigrants in the area also casting ballots for the first time.

The work ACANA is doing to help bring voters to the polls feels familiar to former Philadelphia Mayor Wilson Goode, who began his political career just to the north of 11th Precinct along Cobbs Creek Parkway.

In the 2016 election, voter turnout there hit 76%, one of the highest rates in the city. While only a single rail line separates the leafy 25th Precinct district from the district to the south, the area is wealthier: 30% fewer families live in poverty there. Today that precinct is made up of mostly older African American residents and fewer immigrants, but when Goode got his start in the 1960s, it was in flux.

“That blue-collar area changed from primarily working-class whites to African Americans,” he said. “Southwest Philadelphia has been a changing community for the last 50 years,”

Goode said he and Democratic ward leaders built a political operation to mobilize the newly arrived Black voters.

“We had strong voter turnout in that area,” Goode said. “We kept our area organized and structured.”

Goode said he watched the larger neighborhood “completely transformed” again over the last several decades, this time by an influx of immigrants. He said his congregation on Woodland Avenue recently sold its building to an Ethiopian church. But while many Black families have remained in single-family homes that they own in the 25th Precinct, the availability of apartments and businesses opportunities farther south continues to attract new immigrants.

The former mayor said these decades-old trends were likely still evident in the differing economic and electoral outcomes for the two adjacent precincts.

“It’s the people who moved in, and the income they had in moving in. It’s rental properties versus home ownership. It’s newer properties versus older properties,” he said.

‘We don’t want a civil war in America’

Memories of the civil war that devastated Satte Hoff’s home country of Liberia in the 1990s still loom large, and motivate her to vote.

The Woodland Avenue shop owner lost the father of her four children and recalled walking home from the hospital 30 minutes after giving birth to her youngest daughter, with her baby in her arms, after the facility was attacked.

“That is part of why all the Africans are voting, because we don’t want civil war in America,” she said. “We know [what] it takes for war to be in a country.”

But despite renewed motivation drawn from the tense national political climate and outreach efforts targeting African immigrants in Southwest Philadelphia, many still face the same barriers: a lack of time or familiarity with the electoral process.

Oluatosin Kayode, 26, had been planning to register to vote and cast her first ballot for Biden, but learned last week that the deadline to register had passed.

Kayode, a single mother and nursing student originally from Nigeria, said she had only become a citizen a few months ago, and didn’t know she had to register in order to vote.

“It’s really tough like, being online, with my kids, doing my studies, then I have to go to work,” she said. “There is not really space to do other things.”

Goode placed the blame for low rates of voter participation in the 11th Precinct on the failure of local ward leaders there to adapt to the now decades-old changes in the resident population, and meet the needs of voters like Kayode.

“I don’t think that there is any relationship developed with the immigrant community by the party structure at this point,” he said. “As far as I know, the ward leaders have been there for 25 and 30 years and I don’t think they have adapted to the change in that area. I don’t think there is an outreach to the leadership in the immigrant community to get them involved.”

Both the Democratic and Republican Ward leaders in the area are white and Jabateh, from ACANA, said neither had reached out to his group. (The ward leaders did not return requests for comment.) National Democrats in Philadelphia and across the state have also faced criticism in recent weeks for failing to make inroads with other immigrant communities ahead of next week’s election.

That failure leaves much of the work of turning out voters that skipped the 2016 election to community groups like ACANA — in a way, repeating the cycle of organizing an increasingly established community, much like Goode and other incoming African American residents 50 years ago.

For Aruna Jaward, this election is a tipping point.

The former nonvoter has now changed his Facebook profile picture to urging his friends and family to vote. He plans to encourage as many people in his community as he can until the polls close.

“It’s a great feeling to be able to vote,” Jaward said, smiling after dropping his mail-in ballot into the dropbox. “That’s something I am going to be doing regularly.”

Your go-to election coverage

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.