University of Delaware to explore slavery legacy at the Newark campus

UD joins a consortium studying how the work of people held in slavery, or those who held people as slaves, influenced the history of the schools.

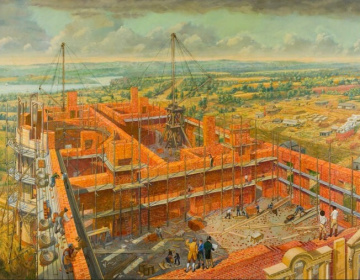

University of Delaware's campus in Newark. (University of Delaware)

As part of an anti-racism effort born out of last year’s nationwide protests, the University of Delaware has launched a deeper exploration of its history as it relates to both enslaved people and the treatment of Black students.

University buildings at the Newark campus were not built using slave labor, unlike schools including the University of Virginia. But that doesn’t mean UD has a clear record when it comes to people held as slaves.

Alison Parker, who chairs UD’s history department, said that the “legacy of enslavement and the dispossession of indigenous people” weaves through the university’s history, which goes back to 1743.

“Something that we can take all the way through to segregation and even the fight for desegregation in 1950, when Black students who wanted to come to UD had to sue the university, and the university actually opposed desegregation at that point. So there’s a lot to look at,” Parker said.

A team of 21 students has been doing the initial research, which will aim to uncover even more of those stories now that UD has joined the Universities Studying Slavery consortium.

“The first line of research was to look at the university archives’ land records, and part of that is to see who did own this land and was the land owned by people who were enslavers or people who held African Americans as indentured servants in long indentures such as 30 years, even in the years after the Civil War, which in fact we have found,” she said.

About 80 other universities have joined the consortium, which is based at the University of Virginia. Most schools represent the southern United States, though some schools in Canada and England have also joined.

UD has a reputation for having a predominantly white student body. A study of 2015 data by the Hechinger Report found that UD had the fifth-highest gap between the percentage of Black high school graduates in the state to incoming Black freshmen.

That report found that while 33% of Delaware high school graduates were Black students, just 6% of UD’s freshman class were Black students. The four schools that had a worse percentage were all flagship universities in the South, including the University of Mississippi, which was the worst.

In 2020, 948 Black students accounted for 5.6% of the full-time UD student body population of 17,034. In 2010, 831 Black students made up 5.2% of the student body of 15,888.

Parker said better exploring the school’s history and talking about its racist past may help increase diversity among the student body.

“Instead of just pretending like everything is fine, I think we need to talk about why are we in the position where people aren’t choosing to come to the University of Delaware, and then what can we do to make it a more inclusive and accepting space,” she said. “One part of that is to be honest about our past and about the problems that we’re still facing, because that’s the only way that we can move forward.”

Last year, in response to protests for racial justice following the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd, UD president Dennis Assanis said the school “can do better” on diversity.

“I have been truly heartbroken to hear the stories of discrimination and prejudice that many of you have experienced, whether in our broader society or, unfortunately, here within our own community,” Assanis wrote to students, faculty and staff in June 2020.

UD also announced plans to require all students to go through diversity, equity and inclusion training.

“Through education for all members of our community, we can cultivate a greater appreciation of the value of diverse peoples, cultures and perspectives,” he said.

As researchers dig into the uglier parts of UD history, there’s also an effort to highlight the work of those who took steps to improve diversity on campus. That includes 11 members of the Mu Pi chapter of Delta Sigma Theta, the first Black sorority on UD’s campus. Founded in 1975, the chapter had to fight some fierce opposition from the Pan-Hellenic Council, which had to give its approval of the sorority.

“It was the ’70s,” Mu Pi charter member LaVerne Terry told UDaily in 2015. “Things were not always ‘kumbaya.’”

The research will collect oral histories and memorabilia from sorority members in hope of producing a digital exhibit highlighting the group’s groundbreaking history.

“We hope that by telling these stories and looking at the history and finding out more about Delaware and the University of Delaware and its place in this history, we will actually be a better university in the end and we will be a more inclusive space,” Parker said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.