Temple researchers hope to remove PFAS, microplastics with sustainable treatment method

Water providers are removing toxic PFAS chemicals from drinking water, but current methods are energy intensive. Temple researchers are looking at alternative technologies.

Listen 1:12

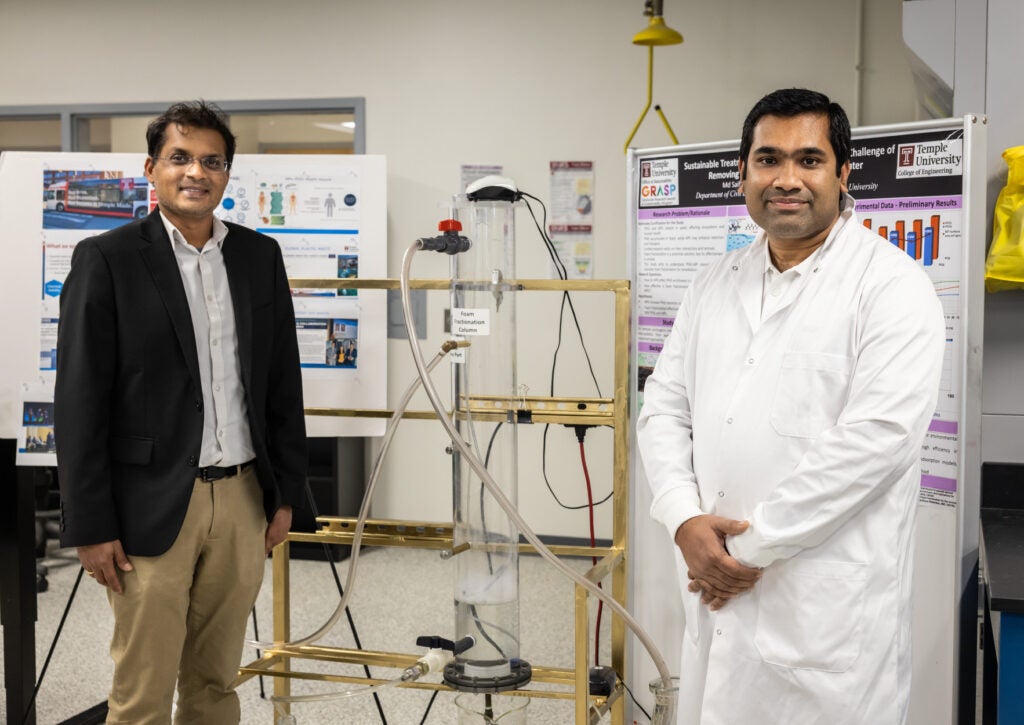

Temple University scientists are researching whether the use of air bubbles can capture toxic PFAS chemicals and microplastics at the same time. (Courtesy of Betsy Manning, Temple University)

This story is part of the WHYY News Climate Desk, bringing you news and solutions for our changing region.

From the Poconos to the Jersey Shore to the mouth of the Delaware Bay, what do you want to know about climate change? What would you like us to cover? Get in touch.

Scientists from Temple University’s College of Engineering are researching whether the use of air bubbles can remove toxic chemicals from surface water before it makes its way to people’s taps.

The goal is to remove harmful PFAS chemicals and microplastics at the same time, and with sustainability in mind. The current mainstay for removing PFAS is effective, but also energy-intensive.

Water providers are required to treat the so-called “forever chemicals” over the next five years. However, there are no federal regulations for microplastics, which can also absorb and carry PFAS in the environment.

“We need to also focus on the microplastic, because PFAS adsorbs onto the surface of the microplastic,” said Saiful Islam, a PhD student in Temple’s environmental engineering program. “Most of these emerging contaminants coexist in our environment, as well as the aquatic system, and all of these contaminants interact with each other.”

PFAS, a chemical widely used in consumer products such as nonstick cookware and waterproof clothing, as well as in firefighting foam, have been linked to serious health problems, including some cancers.

The health risks associated with PFAS, which can stay in the human bloodstream for years, have sparked numerous lawsuits against chemical manufacturers, such as DuPont and 3M.

Water providers are required by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to reduce “forever chemicals” to almost zero by 2031.

Islam said foam-based technology could help water providers meet the new regulations.

His research, which is in the early stage, involves the use of air bubbles to create a foam that aims to capture PFAS and microplastics from surface water. The goal is to filter the contaminants before they enter the treatment plant.

PFAS have hydrophobic tails — meaning they are repelled by water. When the air bubbles are introduced to the water, the hydrophobic tail is drawn to the bubbles and becomes trapped on its surface. As the bubbles rise, they carry the contaminants, which can then be separated and destroyed.

The foam-based technology can avoid the use of toxic chemicals, and is more energy efficient than current methods of removing PFAS, Islam said.

Most water providers use granular activated carbon, which is currently the most affordable and effective way of removing “forever chemicals.” However, the technology can have environmental impacts.

To produce activated carbon, which is made from coal, it must be subjected to significantly high temperatures. That process can release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Once the activated carbon is used to eliminate PFAS, the materials must be disposed of — sometimes through incineration, or by sending it to a landfill.

Activated carbon can be recycled for reuse, but that, too, requires a lot of energy.

Gangadhar Andaluri, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Temple, said the foam-based technology could help reduce energy and waste. The goal is to treat contaminants directly from surface water before it enters the treatment plant.

“If we can use these air bubbles and push out PFAS before they even enter the initial treatment phase, it might be more helpful,” said Andaluri, who is Islam’s faculty advisor.

Though water providers are required to remove “forever chemicals” from drinking water, most are not testing or treating microplastics.

Micro- and nanoplastics are tiny particles derived from plastic waste that break down into small pieces, contaminating soil, air, food and water. Once ingested, they can bioaccumulate in the body.

“Research shows that nanoplastic is detected in our human heart and lung tissue. So, that’s why everyone is concerned for this contaminant,” Islam said.

Detecting microplastics is difficult, however, and research on treatment options has shown inconsistent results.

“Nanoplastic is a very tiny particle, less than one nanometer. So, there are significant challenges to detect and extract them,” Islam said.

Nonetheless, the Temple researchers said it’s crucial to determine whether treatment options can eliminate multiple emerging contaminants. Andaluri said though the team didn’t analyze co-contaminants of microplastics, evidence suggests they can interact.

“When the contaminants are flowing in the river, they have a lot of time. They’re exposed to all kinds of environmental conditions and there might be some interactions,” he said. “There is a chance that they can attach, and if we are able to remove one of them, we might be actually removing multiple.”

Saiful and Andaluri have tested samples from the Schuylkill River, and the foam-based technology has been effective at removing some types of PFAS and microplastics to almost zero. The team’s next steps are to partner with local wastewater utilities to conduct more research.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.