Swedish museum offers a glimpse into the origins of modern tattooing

The Swedish American History Museum features a glimpse into the origins of Philadelphia’s tattoo heroes.

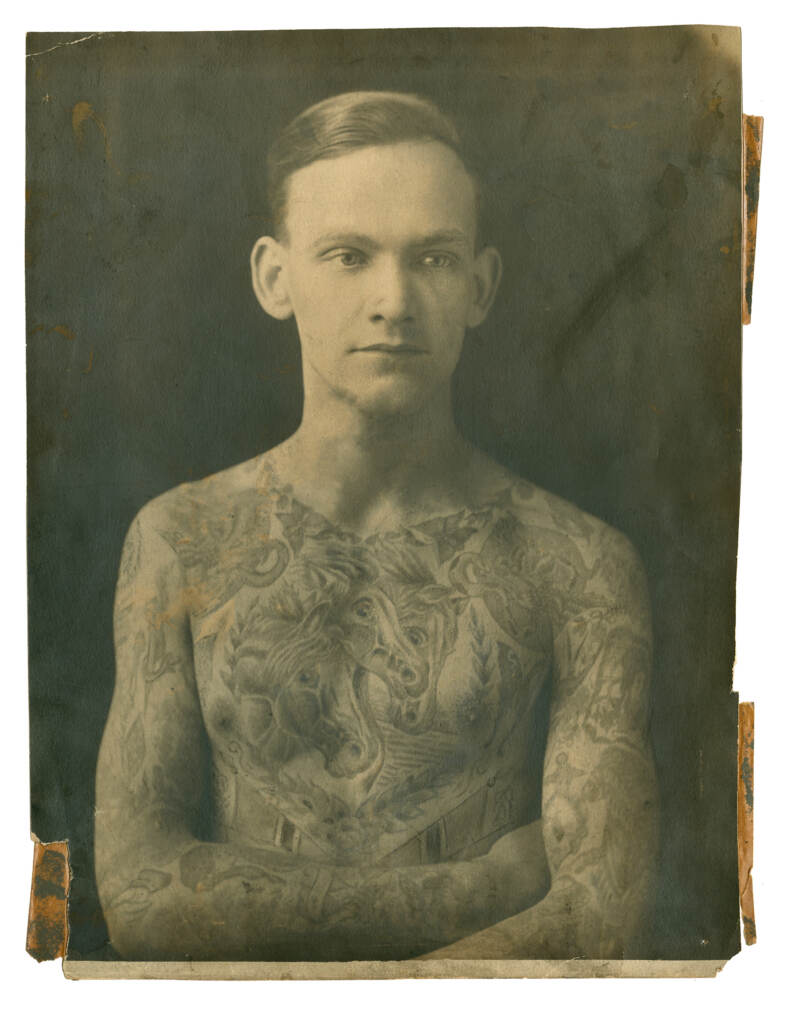

Harry ''Buckie'' Buchanan was a Philadelphia tattoo artist at the turn of the century. He kept a low profile but was very influential among other tattoo artists He was known for his ''flapper'' looks. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

An artifact from the early days of tattooing in Philadelphia is included in a new exhibition at the Swedish American History Museum, in FDR Park.

Harry “Buckie” Buchanan’s name may not be widely known to tattoo enthusiasts, but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries he was considered the tattooist’s tattooist. Buckie influenced generations of tattoo artists, giving some of them ink into their own skins.

“He was part of this generation that really interests me: guys just started tattooing in the late 19th century right when electric tattoo machines were introduced,” said Derin Bray, an historian and collector of vintage tattoo artifacts. “He’s one of these early adopters of electric tattoo machines. As part of this generation that popularized and professionalized tattooing, he’s doing really important work.”

A rare panel of Buchanan’s flash art dating from the 1930s is included in “Tattoo: Identity Through Ink,” now on view at the Swedish museum. The show explains the history of tattoos, which goes back over 7,000 years. Egyptian mummies have been found with traces of ink in their preserved skin, and Japanese clay figurines dating to 5000 BCE have been found with what appear to be tattoo-like decorations.

The exhibition pays particular attention to the Nordic origins of tattoos. The Vikings had “green lines from head to foot,” according to early descriptions written in what is now Russia, although no drawings or physical evidence of Viking body art has been discovered.

If ancient Nordic tattoo style has been lost to time, modern “neo-Nordic” styles use symbolism associated with Vikings and the Norse mythology, such as runes and Thor’s hammer. The exhibition points out that much of the original meanings of those ancient symbols have been bastardized in recent years by neo-Nazi and white supremacist hate groups, which have co-opted those symbols for their own purposes.

“Tattoo” highlights one pioneering Norwegian tattoo artist, Amund Dietzel, who joined the Norwegian navy at 14 years old. He is believed to have gotten his first tattoo at age 15, ultimately most of his body became covered with ink.

He learned how to tattoo at sea as a teenager. When he was shipwrecked off the coast of Quebec in 1907, at just 16 years old, Dietzel made his way to America where he traveled throughout the country performing as the tattooed man in sideshow circus acts.

As with most tattooed circus performers, Dietzel’s body was a form of advertisement for his side hustle: giving viewers tattoos after the show.

“They would draw people in through the spectacle, and then behind the sideshow tent they have a little booth set up tattooing,” said Bray, who publishes books on tattoo history on his imprint Rake House. “They did that in carnival sideshows traveling across the country. It was really through the sideshow and circus that tattooing became popularized, and introduced to rural communities.”

Dietzel eventually settled in Milwaukee, where he ran storefront tattoo shops. He used what was then standard tattoo imagery of nautical themes, pretty women, and hearts with banners, and infused them with clean, bold lines, and modern Art Nouveau and Art Deco stylings.

He became a highly influential mid-century American tattoo artist, dubbed the “Master of Milwaukee” and the “Rembrandt of the rind.” He continued working in Milwaukee until 1967, when the city outlawed tattooing.

“At least it took the city 51 years to find out it doesn’t want me,” Dietzel was known to have said at that time. “Milwaukee used to be a very nice town.”

“Tattoo: Identity Through Ink” was developed by the Vesterheim Norwegian-American museum in Iowa, which put it on the road as a traveling exhibition.

The Swedish American History Museum in Philadelphia picked up the show to be able to trace how important tattooing is to the Swedish. About 47% of Sweden’s population is tattooed, making it the second-most tattooed country in the world, per capita, behind Italy (48%) and above America (46%).

“One of the biggest things that we’ve been doing recently for this museum is opening up our mission statement from just being about Swedish immigration to America to different Scandinavian countries,” said curator Christopher Malone. “The fact that this exhibition had a large portion dedicated to a Norwegian immigrant is why we chose for it to come here.”

Malone added additional material to the show, including a traveling tattoo case hand-built by Dietzel. An accomplished woodworker, Dietzel was ever the showman, so his trunks holding a tattoo kit along with ink and flash art were made with extravagant flourishes and hand carved details. The one on display in the exhibition is painted bright pink with Art Deco detailing, with his name carved on top.

Malone also borrowed from a collector several sheets of flash art by the Swedish-born tattoo artist Dick Swanson who immigrated to Boston in 1911. He mostly worked the sailor trade in port cities, later relocated to Newport, Rhode Island.

Malone said he wanted to bring the exhibition closer to home by including Philadelphia tattoo history, so he borrowed from Bray the vintage flash art by Buckie Buchanan, likely from 1915. Buckie was among the first tattoo artists who turned the underground art form into an industry.

“They were developing standards and professional practices,” said Bray. “Prior to Buckie’s time, there’s no supply catalog. You’re not going to find a pamphlet selling machines and inks and needles. It didn’t exist. There isn’t much in the way of advertising. There weren’t any street shops. He very much pioneered the early days of professionalizing and popularizing tattooing.”

Unlike many other tattoo artists – like Dietzel – Buckie was not flamboyant. Bray said he kept a low profile. It’s rare to find photos or newspaper advertisements associated with Buckie, making him obscure even to historians.

“He was one of these quiet tattooers,” said Bray. “I’ve been researching and studying Buckie, he’s been on my radar for almost a decade, but this group of flash art only turned up three or four months ago. It just came out of the woodwork. I couldn’t believe it.”

During the run of the exhibition until May 1, Malone expects to bring additional local Philadelphia material into the show, including artifacts from Crazy Philadelphia Eddie, the legendary tattoo artist with a shop in Chinatown who died in 2016, at age 80.

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that the historian’s name is Derin Bray, and Harry Buchanan’s flash art panel dates to the 1930s. We regret the errors.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.