‘Artists need to be seen’: A private collection of works by young Black artists goes public

The Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection is on a mission to amplify the stories and works of young Black artists.

Left: Untitled Kara Walker, 'Untitled 1', 1995; Right: Wilmer Wilson IV. 'Pres' (2017). (Courtesy of The Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection)

An exhibition of work by contemporary Black artists is opening at Lehigh University today. The 50 works in the traveling show called “Young, Gifted and Black” all come from a single private collection — a collection on a mission.

“A collection should be a story. It should be an argument. There should be a thesis to your collection,” said Bernard Lumpkin, who with his husband Carmine Boccuzzi has collected almost 500 works of art by mostly emerging Black artists of the last 25 years. “For me, that thesis has to do with telling the stories of young artists of African descent, whose work has not been shown, whose careers have not been promoted, and whose vision has not reached wide enough audiences.”

The Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection was the subject of a book published in 2020, and now is an exhibition that has already been in New York and Chicago. The exhibition at the Lehigh University Art Galleries, which runs through the end of May, includes work by high-profile artists, such as Kara Walker, Derrick Adams, and Rashid Johnson.

There are two Philadelphia artists in the show: Wilmer Wilson and Jonathan Lyndon Chase.

“It’s really, really beautiful to be working and living at the same time with all of these like like-minded humans,” said Chase. “The word that comes to mind is time capsule, which I think is super important. It’s an honor to be documented in such a way.”

Chase said it’s rare for a private collector to put their acquisitions out in public, in a traveling show.

“I might get lucky and, like, the person will send a picture of where it is,” they said. “What Bernard is doing is in that way super duper vital and special, because artists need to be seen.”

A mission to ‘preserve cultural capital’

Lumpkin, a former MTV executive who worked on documentaries like “Choose or Lose” and “Rock the Vote,” was inspired to start collecting seriously after the death of his father in 2009, from cancer.

As a Black kid from the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles who grew up to be a physicist and professor at the University of California San Diego, Lumpkin said his father was always helping to make opportunities for younger generations to get ahead. The art collection is meant to follow in those footsteps.

Lumpkin makes a distinction between being a collector and being a patron. It’s one thing to acquire art; it’s the patron who uses the art as a social endeavor.

“Being a person of color, being Black, I think that’s an important mission,” he said. “There are a group of us Black collectors who, you know — there’s a sense of mission and purpose which extends beyond our individual investment. It’s a greater sense of purpose, passing down what it means to preserve cultural capital from one generation to the next.”

The exhibition is curated by Matt Wycoff and Antwaun Sargent, who edited the book on the collection. Together, they assembled pieces from the collection that address Black identity and representation. Many of the pieces celebrate Black figures, like Mike Tyson’s face painted as a brick wall in Derrick Adams’ “The Great Wall,” and Vaughn Spann’s double-headed figure in baseball hat and Day-Glo shirt.

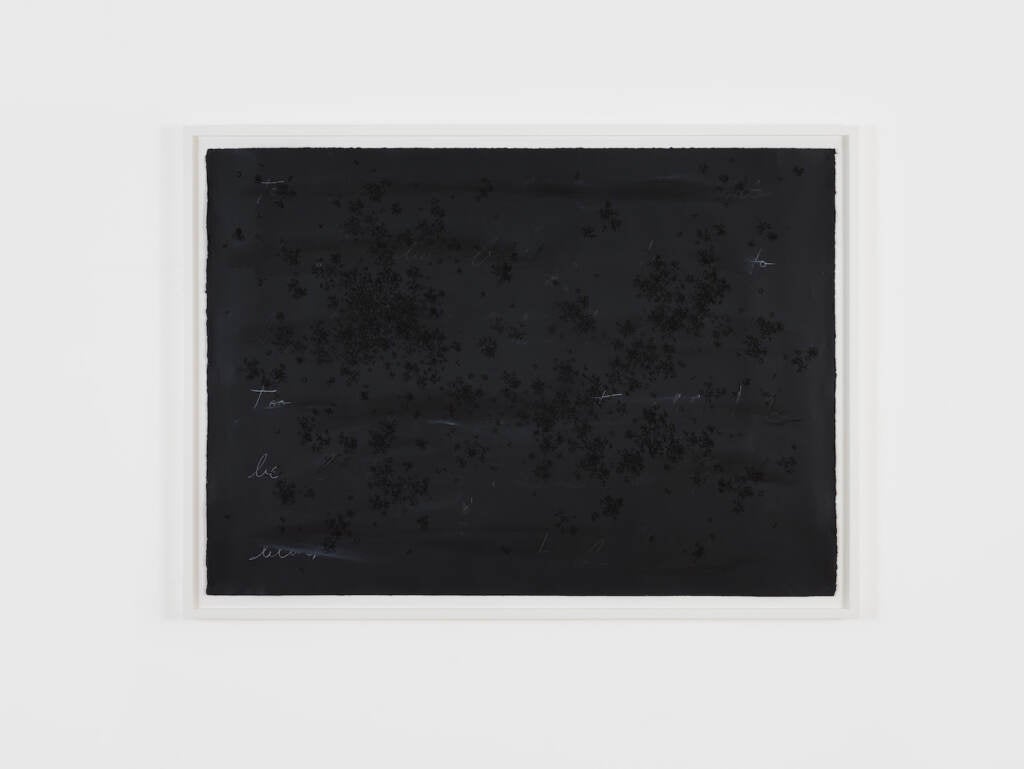

More abstract pieces lean into the color black, like Bethany Collins’ “Too White to be Black,” a field of black paint scrawled with mostly erased words written in white chalk, linking racial identity with the uniformly homogeneous color.

Wycoff writes in the exhibition’s essay that some of the artists were reclaiming the color black “as it exists inside the racist mind — monolithic, impenetrable, and terrifying.

“Hard-earned reclamation of the color black dramatically underlines one of the most striking visual shifts presented in ‘Young, Gifted and Black:’ a riotous and radical explosion of color, primarily among the younger painters, to represent the human form,” wrote Wycoff.

Chase, who recently had a large solo show at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, said he thinks of his canvases as bodies, assembled with many layers of figures, colors, and symbols that are often very subjective and personal.

“Thinking of my practice as this moving, in flux, unidentifiable but familiar body, identified as non-binary,” they said. “There’s lots of things about gender and sexuality and performance.”

Lumpkin has bought several of Chase’s works since they met in 2018. Lumpkin said one of the advantages of collecting contemporary art is he gets to meet and form relationships with the artists.

Lumpkin is attracted to artists who he believes are reinventing their medium, shifting the parameters of photography, painting, collage, and sculpture to tease new meanings out of them.

Another artist in the show, Wilmer Wilson of West Philadelphia, makes paintings out of staples. A single work on a panel can contain tens of thousands of tiny metal staples arranged in nuanced patterns that form into figures.

“I think what’s so exciting about emerging artists is that they are literally in the process of redefining art practice today as we know it, regardless of race, regardless of gender,” said Lumpkin. “They’re showing us what a painting can be, showing us what we thought a photograph could do and showing us something new that a photograph can do. They are simultaneously working within a tradition, but they are also redefining that tradition.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.