Police clear PATCO encampment as City Council challenges Philly’s homeless strategy

Philadelphia’s top homelessness official defended the city’s strategy for housing people in need and pointed to long-term funding challenges.

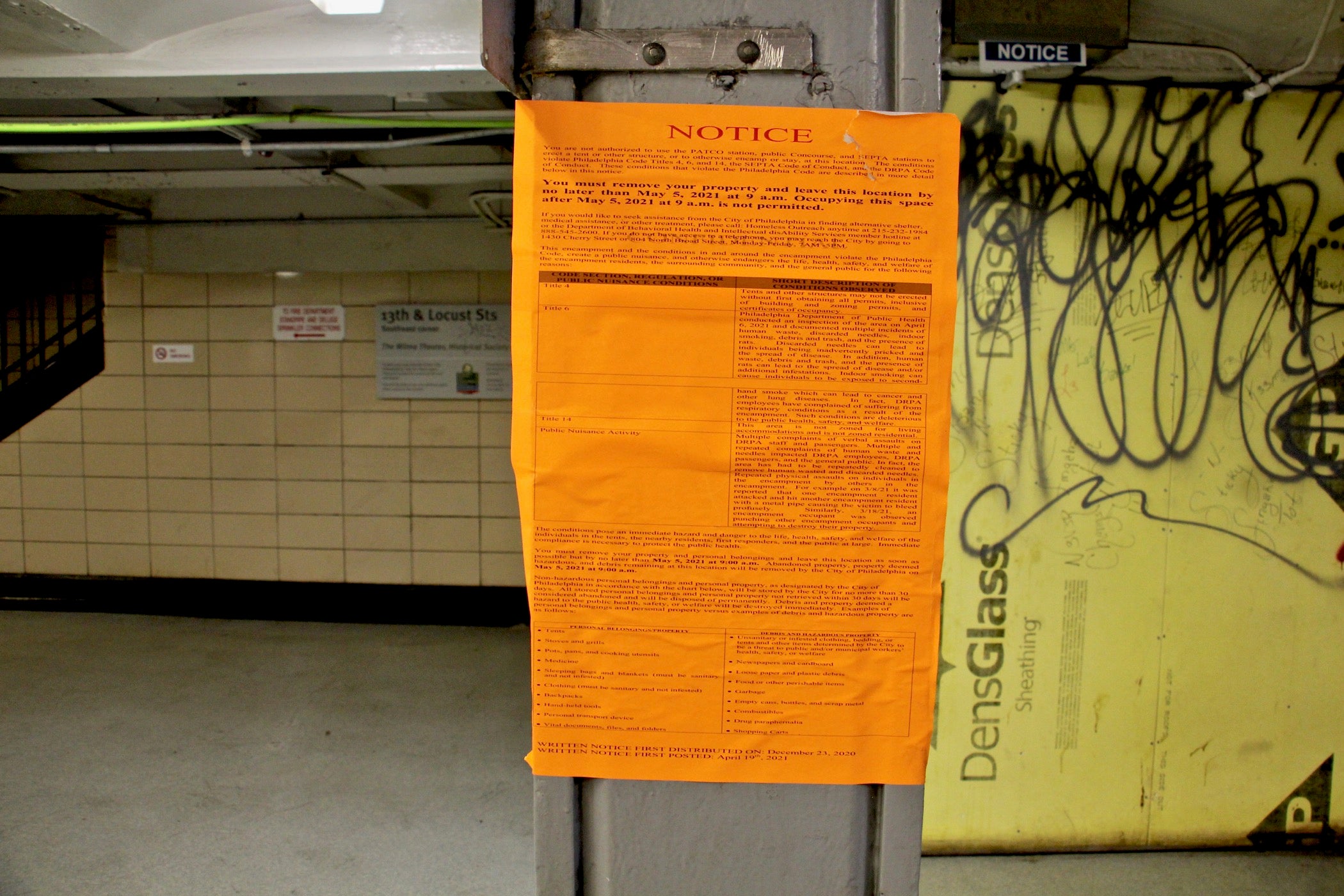

Philadelphia cleared out a homeless encampment at the 12th/13th Street PATCO station on May, 5, 2021. By the afternoon, at least one occupant had returned. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Philadelphia City Council demanded answers on the strategy for connecting more people experiencing homelessness with longer-term housing in a budget hearing that began shortly after police cleared an encampment from a subway station.

Police administered removal of the encampment at the 12th and Locust Street PATCO stations Wednesday morning but did not allow press access during the removal. Unhoused people have lived underground there since at least December, seeking warmth and shelter. By 1 p.m., tents had been cleared and all evidence of the encampment gone. All that remained were notices posted that said people had to leave by 9 a.m Wednesday morning.

Sparks, one of the people evicted from the PATCO encampment, described being there as “a survival thing.”

“We came to live and be a community for the simple fact that we [have] been basically barred from other spaces,” they said. “It’s not what it looks like, like we’re trying to bully the subway or something like that. It’s more like we came to cure our pains.”

The Office of Homeless Services said at least 42 people out of the roughly 75 encampment residents have accepted housing and treatment services. OHS also said it gave notice on April 19 that it would disband the encampment and that they sent city agencies there three times a day, five days a week offering services.

While officers cleared the encampment, City Council questioned housing officials and the timing was not lost on Councilmember Helen Gym. She questioned the city’s broader encampment dispersal efforts –– which include the removal of other camps in areas like Kensington, Filbert Street near the Reading Terminal Market and I-676 –– and asked if they merely pushed homeless people to other, less safe locations.

“Resolution is not dispersal, it’s about actually getting people into some housing,” Gym said. “If resolution is dispersal with no clarity to where they’re going, it’s not resolving anything.”

A lengthy and high-profile housing protest last year that took the form of an encampment on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway saw activists blast the city’s Office of Homeless Services over dispersal policies and overreliance on shelter beds. But in hearings, OHS director Elizabeth Hersh countered that her agency sought to transfer encampment residents to social services and, ideally, longer-term housing. She said the city counted some 40 encampments and councilmembers noted they saw homeless people living in city rec centers and other park facilities.

Hersh described an intentional approach to clearing camps, and said the effort, while not fast, yielded success. She said that when city workers cleared the Filbert Street camp earlier this month, outreach staff connected all but one individual with social services.

“One reason we don’t clear them all is because it’s about intensive social service connection,” Hersh said, referring to various other encampments around the city.

Hersh said the city used both shelter beds and rapid rehousing funds, which can cover up to two years of rental costs to immediately place many individuals, and noted that subway stations were a poor alternative to more sustainable housing options.

“In PATCO, there’s no bathroom facilities,” she said. “It’s a really unhealthy situation for people.”

‘We do very much have a plan’

Hersh said that while more publicly visible, chronically homeless individuals remained, the overall unsheltered population had declined to about 700 people. She said the city’s long-range strategy was to move chronically homeless people into long-term housing — a strategy that had a 90% success rate — but that the city would need about 2,500 additional, subsidized housing units to meet demand.

“When we do have a penny, we try to put it into long-term housing,” she said. “We do have people living in shelters who should not be in shelters.”

However, while the office had benefited from federal housing relief funds in both 2020 and 2021, funding restrictions conflict with the strategy. Hersh said the federal government had not earmarked funds for longer-term housing and her office was still determining how to allocate.

Hersh said that she hopes to get $42 million worth of federal aid in September for longer-term housing. Affordable housing is the solution to homelessness, she noted.

“We don’t have a plan for the new money yet,” Hersh said. “But we do very much have a plan.”

But Gym and others remained critical of the picture presented by the OHS director.

Gym pointed to a past study that found the school district was undercounting the number of young people experiencing homelessness and questioned the accuracy of OHS’s data on housing outcomes. A spokesperson for OHS said the Research for Action study cited focused exclusively on school district data and asserted “there is no evidence and have been no charges that Philadelphia is undercounting people who are homeless.”

Others, like Councilmember Kendra Brooks, questioned the full efficacy of the department’s strategy, saying the prevalence of chronic homelessness was clear downtown.

“It looks like there’s a continual shuffling of people experiencing homelessness,” Brooks said. “You can take a short walk in Center City and it illustrates the housing crisis and the limitations of the shelter system.”

Housing activists were also busy raising concerns about OHS’s anti-homelessness plan this week.

Both activists and unhoused residents protested outside of Hersh’s house Tuesday ahead of both her testimony and the camp removal.

The organizers included ACT UP Philadelphia and the National Union of the Homeless. They demanded the reopening of bed space in hotels utilized earlier in the pandemic, a halt to evictions, more permanent housing, and the creation of an oversight board for OHS made up of shelter residents and unhoused people.

“Homeless people don’t have a place to go so they can not be bothered,” Jamaal Henderson, an organizer with ACT UP said. “I was homeless…I know what these people feel and what they’ve been through…so I have absolutely no shame being here harassing Liz [Hersh] and will continue to do it until she does her job in a way that is equitable to everyone in the city.”

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.