Philly’s fave Afrofuturists turned a Fairmount mansion into a time-travel portal

The Hatfield House in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park is the site of an Afrofuturist vision of time travel by the art duo Black Quantum Futurism

Camae Ayewa (left) and Rasheedah Phillips (right), the artists of Black Quantum Futurism and makers of the film “Write No History” with their work in Philadelphia’s historic Hatfield House. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The Hatfield House, a preserved 18th century farmhouse in Fairmount Park near Brewerytown, has its own rich history. The Greek Revival building was originally constructed about four miles north, near Germantown, where it had served as a private residence, a boarding school for girls, and a summer retreat for a wealthy Philadelphia doctor, Nathan Hatfield.

It was then moved, piece by piece, to 33rd and Girard where since 1930 the building has been used as a house museum, nonprofit office spaces and now, a community arts space operated by Fairmount Park Conservancy.

What if the house also served as a time-travel portal used by a secret society — the Temporal Disruptors – whose members communicate across centuries?

“The Temporal Disruptors are speculative,” said Rasheedah Phillips, one half of the artistic collaboration Black Quantum Futurism. “It’s actually based on Black scientists and doctors who lived in Philadelphia, spread out across time and space, who are often left out of history, often left out of the narrative around Black communities and what we’ve done in history.”

“It’s not imaginary,” added Camae Ayewa, also known as Moor Mother, the other artist in Black Quantum Futurism. The Disruptors feature figures such as Mae Jemison, the first Black woman astronaut, and Leon Sullivan, an entrepreneur who developed Progress Plaza, America’s first Black-owned shopping center, in North Philadelphia.

“It’s drawing on very real histories and, yes, there is speculation in it,” Phillips said. “We have to speculate as Black people on our histories and on our futures, because we’re so often cut off from the future, so often left out of history, and so often compressed into the present.”

What’s speculative about BQF’s installation in Hatfield House, called “Ancestors returning again/this time only to themselves,” is that these Black scientists, doctors, writers, and engineers across wide expanses of time are able to communicate with one another, using messages and artifacts that move back and forth through time.

The time travel portal for the imagined secret society: Hatfield House.

What is Afrofuturism?

Phillips and Ayewa’s artistic practice is rooted in Afrofuturism, a cultural, literary, and aesthetic movement that centers the Black and African Diaspora experience in the context of technology and science fiction.

Both from North Philadelphia, Phillips and Ayewa started working together several years ago, creating a long string of projects in Philadelphia and around the world that have cumulatively built up a complex narrative involving time travel linking the past and present with imagined futures.

Many objects created for previous projects have returned in “Ancestors returning again,” including assemblages of shells and tiny watch parts, portraits of African Americans, African textiles printed with mathematical equations and graphs, and pamphlets of printed prose.

The artists reference the history of Hatfield House, itself, as the former Catherine Mallon Boarding School of Girls. The otherwise empty building has been arranged with furniture where visitors can sit and peruse a photo album of candid pictures of the Temporal Disruptors assembled by BQF. The effect is making the historic house feel more like the home it was for boarding school girls.

“Usually these [photo albums] are kept at some family member’s house, so we don’t always have access to the photo album,”Ayewa said. “I want people to be able to have agency to flip through and decide what they want to look at, or what makes sense to them.”

Time capsules as messengers

The newest addition to BQF’s ongoing Afrofuturist narrative is “Write No History,” a three-channel video with sound design featuring the Temporal Disruptors individually preparing communiqués, sending them through time portals and, then, collectively opening a Black history time capsule to explore its contents.

“Black histories are often left out of time capsules, so we have to think about time capsules in a different way,” Phillips said. “Time capsules that can reach back to the past, to send messages and share a warning, to talk about histories we know in the future that would come in the past. For example, the Red Summer race riots of 1919.”

The Red Summer riots were a series of dozens of attacks by white supremacists on Black neighborhoods across the United States, lasting for most of 1919. The deadliest was the Elaine Massacre in Arkansas, wherein an estimated 200 Black people were killed. Violent attacks in 1919 were also reported locally in Philadelphia, Darby, Coatesville, and Wilmington, De.

The video “Write No History” was shot in Hatfield House and the surrounding area in Fairmount Park. Its title comes from an oral history interview with a former Black slave Henry Blake, recorded in the 1930s by the Federal Writers’ Project.

Blake, who was about 80 years old at the time, described life on an Arkansas plantation as a “bad thing,” but better than working on Arkansas’s notorious prison farm, Cummins, where acts of torture against inmates were later confirmed.

“Out there at the county farm, they bust you open. They bust you up till you can’t work. There’s a lot of people down at the state farm at Cummins…that’s raw and bloody,” Blake told an interviewer with the Federal Writers’ Project. “They wouldn’t let you come down there and write no history.”

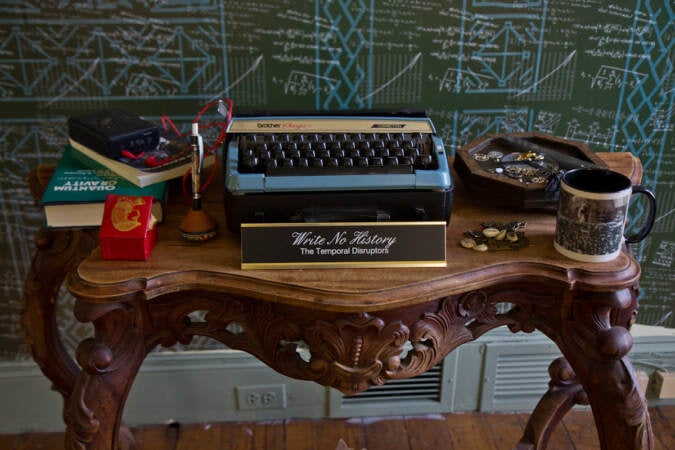

In the Hatfield house, Blake’s words, “Write No History,” are engraved on a desk plaque, in front of a portable typewriter arranged on a carved wooden desk with books, a Walkman cassette player, a coffee mug decorated with historic photos of Black people, and a dish filled with BQF’s signature blend of seashells, brass keys, and watch parts.

The inviting desk assemblage suggests that this room is where both the past and the future will be written.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.