During Ramadan, Muslim leaders hope to shield Philly youth from gun violence

Philadelphia’s gun violence crisis is primarily taking the lives of Black men, and both churches and mosques are dealing with the aftermath.

Listen 5:17

Madeel Abdullah, President National President, Ahmadiyya Muslim Youth Association serves participants small dishes of dates and spicy chickpeas which are eaten as part of breaking the fast during an Interfaith Iftar at the Baitul Aafiyat Mosque on Saturday evening in North Philadelphia. (Jonathan Wilson for WHYY)

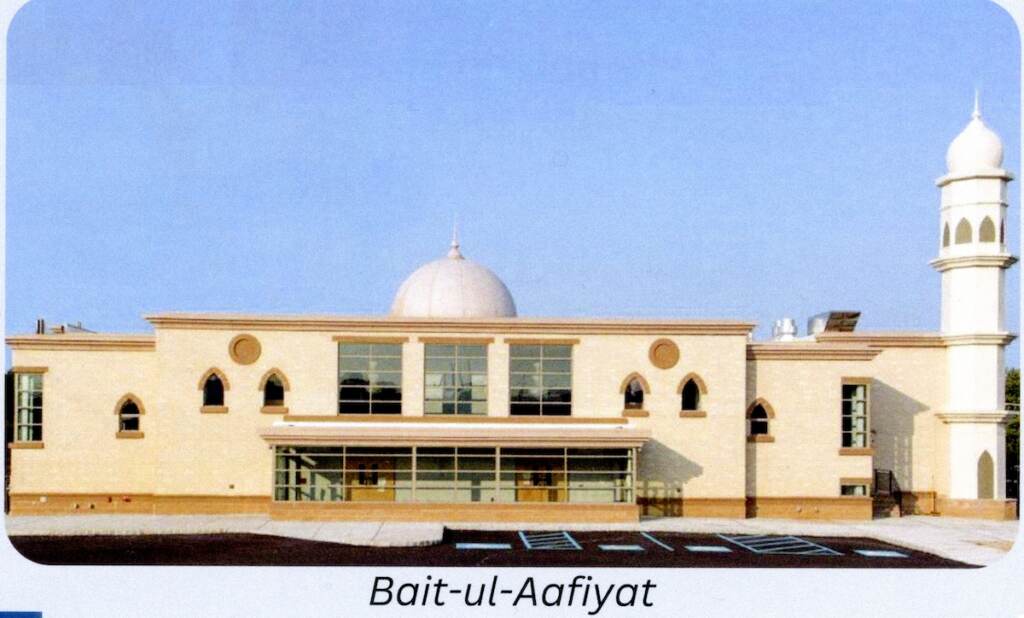

During the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, marked by 30 days of fasting, imam Azam Akram says he’s opening the doors of the Bait-ul-Aafiyat Mosque in North Philadelphia so it may be a beacon of safety — especially for teenagers at risk of engaging in violence.

“We have young Black men here who are a product of this neighborhood,” he said. “We’re trying to develop a little bit of righteousness so that at least that could become something in vogue, that when our young men walk in the communities, they walk with righteousness.”

The mosque is set back from the corner of Broad and Glenwood in North Philadelphia, its large, domed yellow-white exterior protected by a driveway and a black gate.

Just down the block, litter covers vacant lots and the lawns of boarded-up houses. This neighborhood has long been a hotspot for violence, and there’ve been roughly a dozen fatal shootings there this year already, according to Philadelphia Police Department data.

Philadelphia’s Muslim community is taking on the task of preventing gun violence, in part because they’ve been hit hard by it.

Tone Barr, community liaison director at The Philadelphia Masjid in West Philadelphia, said staff there have been performing more and more janazahs — or funerals, for gun violence victims and especially for teenagers.

“The kids are getting younger and younger … the women and children are not even safe no more,” he said.

Barr buried Nicolas Elizalde, the 14-year-old who was fatally shot near Roxborough High School last October.

“And then not even a week later I was burying another 16-year-old who was gunned down from gun violence,” he said. “It was just back to back janazahs for kids that week.”

So far 93% of 2023’s fatal shooting victims in the city are male and 80% are Black, according to Philadelphia Police Department data. About 6% of fatal shooting victims, are under age 18.

Sonnia Brown, a Muslim mother who runs grief sessions for moms who’ve lost children with violence prevention group Mothers in Charge, said faith groups have a responsibility to work together on solutions.

“Whether you’re in the mosque, whether you’re in the churches … we all are tired of burying young people,” she said.

An estimated 80% of Philadelphia Muslims are Black, according to the local chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, compared to only 20% of U.S. Muslims.

African slaves who practiced Islam, including those who were religious scholars, were forcibly brought to Philadelphia in the 17th century from Senegal, Gambia and other nations, said Taseem Siddiqi, a Drexel University historian with a focus in Africana studies. She said historical documents describe African Muslims gathering in Washington Square at that time in an attempt to preserve a sense of community.

“You see the continuities of the practice even though you saw the forced adoption of Christianity in places like South Carolina and Georgia,” she said.

While people of African descent make up the bulk of Philadelphia’s present-day Black Muslim community, Siddiqi notes that there was also a high rate of uptake among Black Philadelphians in the mid-1950’s, when civil rights activist Malcolm X began ministering at the Nation of Islam’s Temple 12 near Cecil B. Moore Avenue and 26th Street according to the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education.

“Because of our experiences with slavery and apartheid, we’ve been very involved in the Black freedom struggle,” said Siddiqi, who is Muslim. “We’re on the front of a radical human rights movement — fighting for housing, fighting gun violence.”

Bilal Qayyum, a longtime gun violence activist who is Black and Muslim, recently spoke at a public forum about the crisis and called on Muslim leaders to step up.

“In the Black community it’s clearly the fastest-growing religion,” he told WHYY. “So the more imams are involved in the mosque and talking about what’s going on in the streets … It could have an effect on what’s happening in the city.”

Starting early

On a recent afternoon at Bait-ul-Aafiyat, a trio of teenage boys lounged in the mosque’s main lobby, playing on their phones and waiting for the iftar, or nightly fast-breaking.

Tahjir, 16, wore traditional garb he said he mostly saves for Ramadan — a turban and a long, white shirt called a thobe.

He and his younger brother grew up Muslim, and started attending services here earlier this year. He says being part of the mosque keeps him “out of trouble.”

“Not like everybody else not carrying guns and doing drugs and all that,” he said. “It helps me stay focused on stuff.”

About a week ago, their friend Bruce, 15, started to tag along. Bruce said he likes the way his Muslim friends carry themselves.

He said if more kids came to the mosque, there would be fewer shootings on the streets.

“Most people don’t always have somewhere to go where they could just chill and pray,” he said. “It’ll keep kids out of danger, especially the younger kids that’s not in danger yet but slowly making their way there.”

The mosque runs after school programs where young people learn the tenets of Islam, play basketball, and get help with schoolwork.

About one third of U.S. adults don’t affiliate with a religion according to a 2021 Pew Research Center survey, up from just 16% in 2016.

Barr, with the Philadelphia Masjid, said the younger generation’s shift away from faith, and toward video games and social media, has contributed to the violence.

“These kids are lost … these kids don’t have a religion,” he said. “It’s sad.”

Rev. John Hougen with the Religious Leaders Council of Greater Philadelphia, which represents 29 different faith groups, said even though the “statistics are pretty grim”, there are young people all over the city who have reconnected to faith.

“[They’ve] found the purpose in their lives and have been given the tools that they can use, so in their maturation they can not only avoid getting involved in violence themselves but bring their friends along with them.”

But Barr worries that even if faith leaders can get children through the doors for programs and prayer, it won’t put an end to conflicts on the streets.

“You can come to the masjid for a safe haven, you can come to a church for a safe haven, but once you go outside what’s gonna happen?” he said. “Really, where is the safe haven at?”

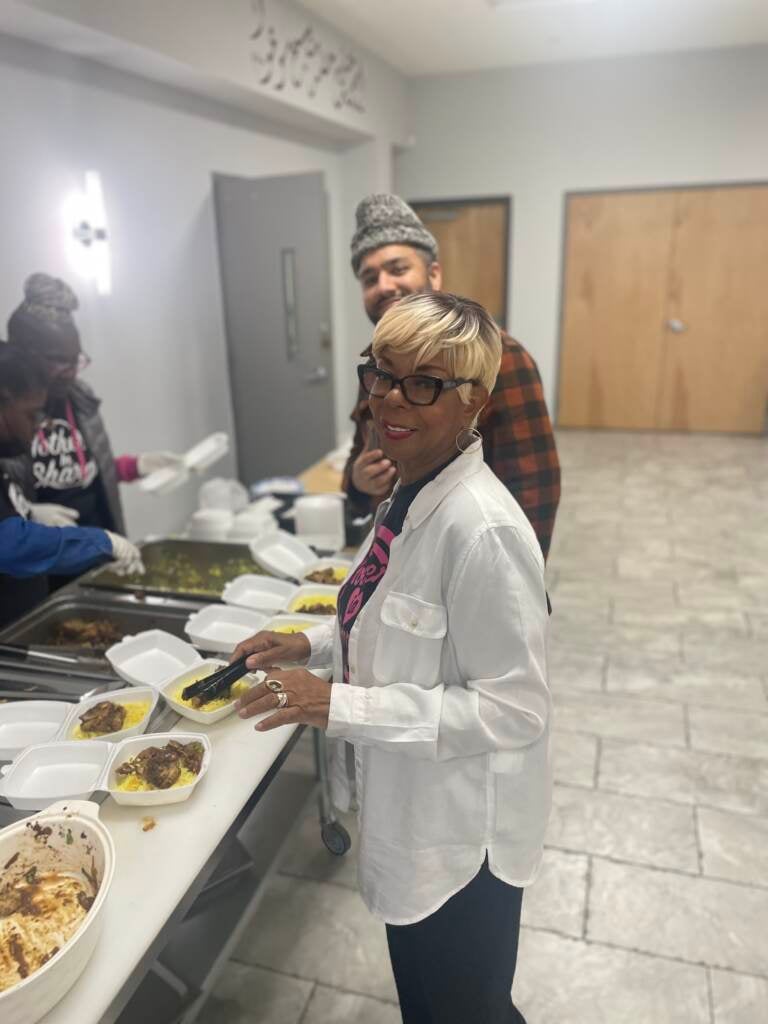

(Jonathan Wilson for WHYY)

In recent years, Philadelphia mosques have had the dual task of grappling with active shooters targeting mosques and shielding members from the violence in the surrounding streets.

Last spring, the Germantown Masjid hired extra security on Eid, the last day of Ramadan, “to ensure the wellbeing and safety of the people,” according to a May 2022 press release.

Despite all of that, Terri Veracruz, who is Christian, said she felt her son Terrell became safer when he started spending time at a mosque in his 20’s. She said the religion “kept him structured” and “made sure he was around good guys.”

“I was just happy that he chose a faith, that he knowed there’s a higher power,” she said. “It raised him up to be a better man.”

But it didn’t ultimately protect him — her adult son was fatally shot about a month ago.

As Veracrruz mourns him, she’s also looking for ways to protect other children from gun violence.

“We have to have some type of program for ‘em,” she said, noting that parents and educators can keep a closer eye. “You can’t say you don’t know where these kids are. They just gotta get better, and they gotta listen to the kids.”

‘A lot of prayer, and a lot of hands’

Earlier this month, members of Mothers in Charge joined imam Azam Akram of Bait-ul-Aafiyat to distribute meals to residents, with the goal of connecting people to both mosque happenings and grief resources.

“It was an opportunity for us to get the word out, it was a win-win,” said Mothers in Charge founder Dorothy Johnson-Speight. “The bullet doesn’t have any name, and it doesn’t have any religion … we need a lot of prayer, and a lot of hands.”

Philadelphia faith groups have long been involved in the fight against gun violence — and some are approaching the issue with renewed fervor as homicide tallies have topped 500 two years in a row, according to police data.

Last May the Philadelphia Masjid, along with Mothers in Charge, hosted a Day of Serenity for families affected by gun violence featuring therapy, prayer and a meal.

The Black Clergy of Philadelphia is spearheading the 57 Blocks Project, pushing the city to clean up neighborhoods that have become dilapidated due to lack of investment. An interfaith organization called Heeding God’s Call to End Gun Violence builds memorials and leads public prayers to honor Philadelphians lost to shootings.

Rev. Hougen, who has worked with both groups, said it’s important to encourage that kind of collaboration, to counter the inclination of some places or worship to “seal themselves off.”

“There’s a sense in most traditions, perhaps all major religious traditions, that those institutions can lead both by reaching out to individuals and also by being active forces in the systems that are involved in creating and maintaining a community,” he said.

He said faith institutions can address the root causes of gun violence by combating food insecurity, addressing domestic violence, mentoring children, resolving conflict and revitalizing neighborhoods, including applying for blight improvement grants and pushing government officials for change.

Sajda Purple Blackwell contributed reporting. Blackwell is a member of WHYY’s News Information Community Exchange – a journalism collaborative funded by the Knight-Lenfest Local News Transformation Fund.

If you or someone you know has been affected by gun violence in Philadelphia, you can find grief support and resources online.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.