Philly men redefining masculinity in #MeToo era

The groups look deeper at problems in male culture that contribute to sexual harassment and violence.

Listen 5:50

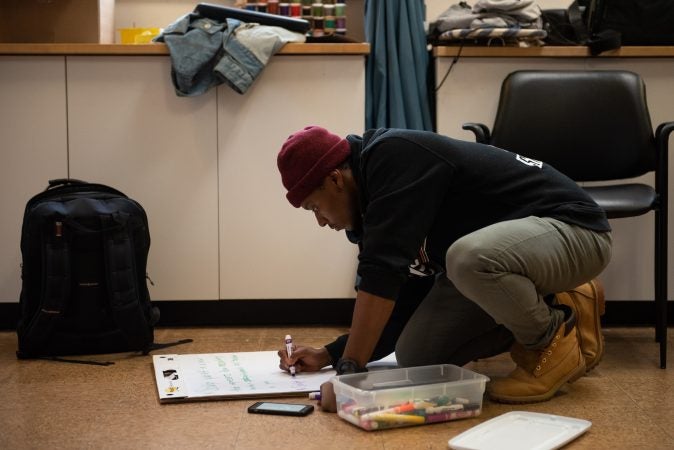

Participants in a masculinity workshop discuss a reading at Lutheran Settlement House on Sunday, October 28, 2018. (Kriston Jae Bethel for WHYY)

Ten men sit around tables at the Philadelphia nonprofit Lutheran Settlement House, playing a card game before they talk about masculinity.

They play competitively, trying to advance to the top table. After the game ends, participants say they’re confused, and frustrated.

What they didn’t know is each table started out with slightly different rules for how to win, so as the winners and losers moved around, everyone was playing with different sets of rules and they were not allowed to talk to each other.

“It took time to realize: ‘oh I know different rules than you do,’ and then yeah the question is do you fight? Do you give up? And it’s like, I think we’re kind of taught to just conform with whoever is the most assertive,” said participant and theatre director Mark Kennedy.

The game is a gateway into more difficult conversations about what it means to be a man, and who makes those rules. The point is to show that there are some common ideas about what a man should be — strong, assertive — but there’s no authoritative rule book that everyone agrees on.

Lutheran Settlement House has been working with men to prevent domestic violence for a few years.

This program is a little different.

The #MeToo movement and the confirmation of Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh have spurred more discussions around consent and sexual assault. This program is one of several in Philadelphia, where men get together to talk about masculinity, and the culture that creates these kinds of problems in the first place.

The participants all want to talk about masculinity. Dwight Dunston says as a kid, he was told not to cry, not to show any weakness, but the game makes him question where those ideas came from, usually his father, coaches, uncles, and cousins.

“Now looking back, I can see the ways that they were also trying to figure out how to be a man and what that means and lots of things being imposed on them,” he said.

Max Ray-Riek identifies as a transgender man, and he says this discussion matters to him because he is about to become foster parents with his partner Kaytee next year.

“It’s tricky because not having grown up as male technically, like in theory I wasn’t socialized to all those patterns of males being caretaken, but I totally was,” he said.

Ray-Riek wants to be supportive and not pass along the same rules of masculinity he was given as a child, like the idea that women will take care of men and do the housework.

“In previous relationships and roommate situations, like, I was the grocery shopper and the chef and the meal planner, but like with a bunch of other people who were so grateful for any food being put on the table, that I got away with stuff. And Kaytee’s like, ‘no I want you to help with meal planning, but also I want things to be healthy and tasty and not the same every time.’ And there’s a super masculine part of me that wants to be like, ‘well if you want it that way, do it yourself!’ ”

And it’s not just talk: the participants have to consult people in their lives who aren’t men and brainstorm what healthy masculinity should look like, and how they can be held accountable.

Facilitator Matthew Armstead got interested in doing a program like this several years back as a student at Swarthmore College.

“Before, I felt like it used to be work,” he said. “Like I did some work with fraternities in the early 2000s, and it was an effort to get men to talk about their masculinity and how that was affecting their behavior … particularly working with one fraternity that said they wanted to work … their leadership said they wanted to work, their membership wasn’t necessarily excited about this.”

Facilitator Toby Fraser says the #MeToo movement changed that: “People saying those exact words: ‘I’ve been looking for something like this, thanks for doing it, when’s it start?’ ”

He remembers something from a discussion that happened one evening a few months ago.

“A memorable moment was a Penn student coming saying when we were partway in the big group, just saying like, ‘oh I’m here because I’m scared of getting MeTooed,’ as though it was a verb and a thing that would happen to him,” said Fraser.

Lutheran Settlement House recently started a nine month gender justice training program for men, and organizers at the local nonprofit Women Organized Against Rape are also planning similar programs.

Armstead says more people are talking about masculinity now, but he’s had trouble with it since he was a kid, and his father told him what a man should be like: “‘No, don’t play with those toys. Don’t say that that’s really cute.’ ”

“And since then I have a relationship with my dad and we’ve talked about it, and both gotten to grow, but they were really memorable moments for me. And those moments also reinforced something saying that my queerness and my gayness wasn’t okay, and to be queer was to break the rules of masculinity and to break those rules meant that I would get hurt. And that’s what ended up happening for me through much of middle school; there was a lot of bullying because I just wasn’t following the rules.”

Armstead emphasizes that while it’s a start for concerned men to get together and think about their behavior and where that comes from, he wants men to do more: “the standard for masculinity work right now is so low. If you go to a one evening workshop, people are (saying) ‘thank you so much for really challenging masculinity and patriarchy and the ways in which men hurt people.’ And that to me is not enough.”

He says talking is good, but he also wants men to act.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.