Twenty-two years after being shot, Oronde McClain reflects on caring for Philly’s gun violence survivors

Gun violence activist and survivor Oronde McClain was paired with WHYY host Cherri Gregg to produce a video and written work to show the true impact of gun violence.

Listen 6:00

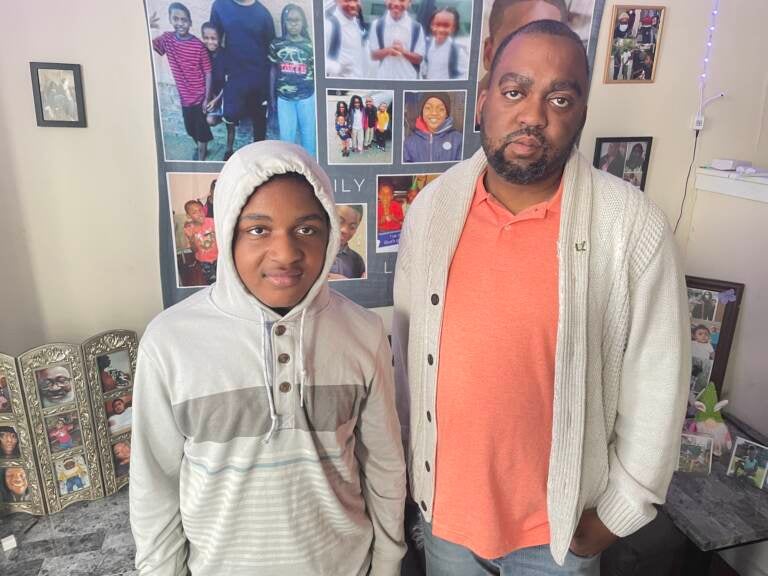

Oronde McClain with Samaj, another survivor of gun violence. (Cherri Gregg/WHYY News)

This essay is being reproduced with permission and support of The Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting as part of the Credible Messenger Reporting Project. The project empowers people impacted by gun violence to report on root causes, lived experience, and possible solutions from the community perspective by pairing a journalist with a credible messenger to create a work of journalism.

This spring, gun violence activist and survivor Oronde McClain was paired with WHYY host Cherri Gregg. Acting as his editor and journalism mentor, Gregg coached Oronde through a process that resulted in the following essay and a documentary produced by Brett Williams.

The documentary will be screened at 5:30 p.m. on Tuesday, July 19, at PhilaMOCA.

___

‘They Don’t Care About Us,’ or do they?

The journey to make “They Don’t Care About Us” began earlier this year when I received the email informing me I had been selected to participate as a community reporter in the Credible Messenger Reporting Project at the Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting. I was so happy I would finally be able to tell the world how angry I am and have been since I got shot 22 years ago.

Since the beginning, my rage has been directed at everyone outside of me — the city of Philadelphia, the state, the system, and the politicians, as well as the people holding the gun. In my mind, the fury is justified: There were over 560 murders last year in my city — that is outrageous — but there were nearly 2,000 shootings where the victims survived. It angers me that no one mentions the survivors or our pain and trauma. That is why I wanted to make this film, to highlight the journey of gun violence victims.

Where it began

The seed of my anger was planted on Monday, April 3, 2000. I was 10 years old. That day I stood waiting in a Chinese store in Mount Airy at the corner of Chew and Sharpnack. My stepmom was supposed to arrive there on the bus at 8:34 p.m. But SEPTA was not on time, so I went outside to check on the bus and didn’t see anything. As I turned around to go back into the store I heard gunshots. I ran back towards the Chinese store, but the owner shut the door suddenly, leaving me trapped outside. In that moment, my life changed forever.

Trauma, recovery, and empowerment

Bullets pierced the back of my head and I fell to the ground. I lay in a pool of my own blood on that Northwest Philadelphia corner, unable to move as the life drained out of me. Luckily, two Philadelphia police officers picked me up and drove me to the hospital in what seemed like 90 seconds. As doctors worked to save my life, I was told that I flatlined for two minutes and 17 seconds. The 10-year-old boy who existed on April 3 died that day — and a new version of me was born.

The next time I remember being awake was seven weeks later. I had been in a coma. Reality soon hit — I couldn’t walk, talk, or do anything on my own. This new version of me spent the next three years in a wheelchair until I could finally put one foot in front of the other and walk on my own. That day was a good day.

Getting shot was traumatic. It hurt my body and my mind, and put me in a dark place. The physical recovery was the most difficult thing I had experienced in my young life. But the emotional and psychological toll was unexplainable. People laughed, teased, and gawked at me throughout my healing process. I could not bear the embarrassment. I was depressed. I wanted to die.

I hate to say this, but I tried to take my life more than 20 times. I will spare you the details, but during my days and years of despair — at no time did I receive assistance from the state or the city. I did not die, so to them, I guess, I was just a number or a file on some bureaucrat’s desk.

The detectives would tell my mom and family that they should be “happy” that they did not have to mourn the death of me. The politicians would say “thank God you’re alive and not six feet under.”

But I thought I was dead. In fact, I wanted death — preferred it — because the pain I felt was unbearable. Why? Because on April 3, 2000, I was a cool 10-year-old that could walk, talk, and do everything on my own. The next day everything changed. The new version of me had to be fed by others. The right side of my body had paralysis. When I slept, I would dream of seeking revenge on the people that teased, laughed, and looked at me funny every day. In my mind, I’d ask the person who shot me, “Why not finish the job?”

At the same time, alongside the anguish was determination. I wanted to become someone with enough power to change the policies and procedures affecting victims and survivors. Why are we looked at so differently than homicide victims? Why are we treated so unfairly? I decided to stop feeling sorry for myself and got motivated. I pushed hard in therapy to make sure that I could be the so-called victim to change the laws and policies that would help “us” get better. I was going to make sure that the next person who got shot wouldn’t leave the hospital thinking they are alone, suicidal, and empty. This project is part of that effort.

The survivors: Samaj, Free, and Leon

I had a chance to work with great people during the making of this documentary. I hand-picked survivors based on my personal conversations with them.

Semaj was a cool kid who never got in trouble. He loved life, and when I met him, I immediately broke down in tears. Samaj, like me, was 10 years old when he was shot in the head. He reminded me of my younger self. He is humble, loves his mom, his twin sister, and his pets. But he, like me, is a survivor still bearing the scars of gun violence.

I met Uhura Russ, also known as “Free,” more than 10 years ago. At the time, she had everything going for herself, including a bright career as a nurse. Free is loving, caring, and humble. But she would always put herself last. I noticed all of this while working with her at a special needs day care. Then I heard her heartbreaking story. She, like me, is a survivor of gun violence who still bears her scars.

Leon Harris is a hard-working guy who grew up living in a single-parent home. He was a church boy who worked two jobs and went to school to help out his mom. When I met Leon, he was so open and cared about my story, as if his story weren’t more amazing. Leon managed to create a beautiful family with his wife and daughter. His wife cares so much about his wellbeing, and everyone knows his plan of care. Leon uses a wheelchair — a constant reminder of the single bullet that changed his life. Still, like Samaj and Free, he pushes forward.

On the front lines

During this documentary, I met inspirational politicians, doctors, and others who help lead the way for survivors.

Among them was G. Lamar Stewart, senior pastor at Taylor Memorial Baptist Church. He’s also the founder and executive director of Taylor Made Opportunities and chief of the community engagement unit of Love Ministry Training. All three of his jobs connect, and he uses his platforms to respond to many of the shootings that take place across Philadelphia.

He loves to bring comfort and support not only to victims and their families, but to the surrounding communities. He cares, and has experienced the pain of gun violence, having lost family members to it as well.

I also had a chance to meet and speak with Philadelphia’s very first Victim Advocate Adara Combs. With her deep knowledge on the impact crime has on victims, I knew she would give the truth that victims like me are looking for. Adara advocates for victims of gun violence, homicide, and other crimes to shift policies, legislation, and systemic issues to better serve them. She wants to meet survivors and victims. She wants to partner with them to change Philadelphia. And she too has been impacted by gun violence.

I also had the pleasure of speaking with Pennsylvania Rep. Darisha Parker. She told me that survivors need to stick together and stay strong if they want to make a change. She said she has an open-door policy and will discuss anything to try to get a law passed. At the same time, Parker noted that she cannot pass legislation alone. She said survivors need to step up and make their voices heard. Parker believes that survivors must create a plan to hold demonstrations, lobby legislators, and make things happen.

Finally, I sat down with Dr. Michelle Joy, director of behavioral health emergency services at the Veterans Affairs hospital. She’s also a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at the Perelman School of Medicine. Michelle explained in great detail how a victim’s trauma can be transferred to families, and how doctors don’t typically recognize the significance that gun violence carries in communities.

What I learned about the ‘They vs. Us’

After spending time talking to gun violence survivors and some of the people working on the front lines to make change, it hit me: Every single person I spoke to cares about gun violence victims. They all do. Each person I spoke to was personally impacted by gun violence, and their lived experience is one of the driving reasons they do this work. They also have families in this violent city who they seek to protect, while doing right by the victims.

During this journey, I realized the documentary’s title, “They Don’t Care About Us,” has shifted in meaning. In the beginning, the “they” was the politicians, police, lawmakers, and anyone who was not a survivor. In my mind, the so-called “they” — even homicide victims — were against me and my fellow survivors. In some ways, I thought they took the easy way out and left “us,” the survivors, behind. I was mad at the “they’s” of the world.

But during the course of this documentary, I learned that many people care. And what’s more — they didn’t shoot me. Instead, I was so self-centered that I didn’t let anyone in. I didn’t give them the chance to show me they cared. Most of the politicians I interviewed ran for office because someone in their family was a victim and they wanted to change the way the system was for the people they love.

In the beginning — the “us” was the victims who were actually shot with the gun. But as I went through this process, I learned that we are all victims in some shape or form. There are so many co-victims, survivors, and others traumatized by incidents of violence that we all suffer a great loss. If we all stick together and form one team, we can help one another.

I would still title the documentary “They Don’t Care About Us,” but I realize now the “they” could be “us,” and the “us” remains “us,” because we all have to care about ourselves before anyone else can care about us.

___

If you or someone you know has been affected by gun violence in Philadelphia, you can find grief support and resources here.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.