Could vibrations help water utilities find lead pipes? Researchers in Philly are trying

The federal government is requiring water utilities to identify service lines made of toxic lead. Researchers in Philly are trying to find an easier way.

Listen 4:47

Using sensors to record sound waves, Drexel engineers John DeVitis (left) and K I M Iqbal (right) can determine if water service lines leading to homes on Osage Avenue in Philadelphia are made of lead without having to dig. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

John DeVitis crouches on the sidewalk in front of a rowhouse in West Philadelphia, holding a small metal hammer in one hand.

He uses the hammer to tap the top of a metal rod sticking vertically out of a hole in the concrete.

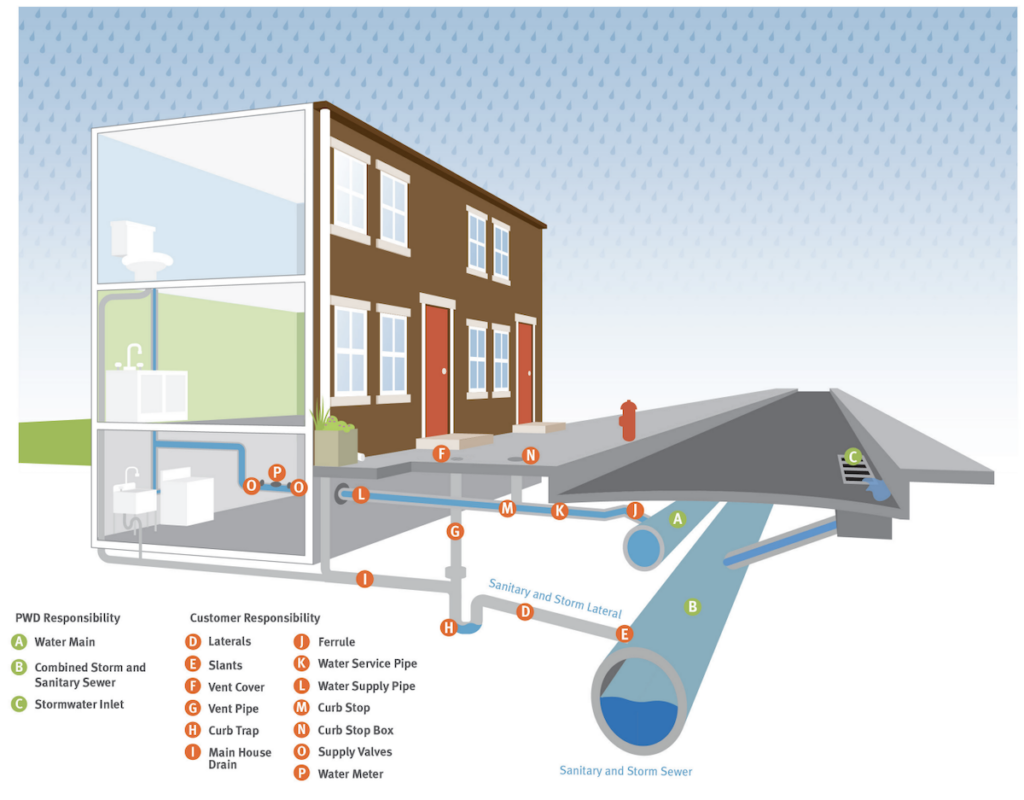

Underground, the rod touches a metal pipe known as a service line that carries water from the water main beneath the street into the home.

With each tap of the hammer, vibrations travel along the underground service line. Sensors placed on the street above pick these up.

“We send stress waves along the pipe, which then propagate through the soil and up to the sensors,” DeVitis said. “The idea is to [figure] out the material type of the pipe.”

DeVitis is part of a team of researchers at Drexel University who are testing out a technique that could help water utilities across the country comply with an EPA requirement to inventory lead service lines, without digging them all up.

“Lead is very detrimental to health, especially for the young children,” said K I M Iqbal, a PhD student working on the project. “We are trying to find … the shortest way to find [it].”

Searching for lead pipes with vibrations

The Drexel lab’s experiment rests on the idea that waves travel differently — for example, faster or slower — through different types of metal.

“If I bounce a hammer off steel, you’re going to hear a ping, a very high-frequency ping,” DeVitis said. “If I do the same thing to lead, it’s going to sound more dull and bass-ier.”

Above-ground sensors pick up these vibrations. Then the researchers analyze this data to identify the unique signature associated with each type of metal.

The challenge is that the vibrations travel through soil and may hit tree roots, rocks, or other obstacles on their way to the sensors, said Ivan Bartoli, a professor of civil engineering at Drexel leading the project.

The experiment is designed as a blind test, Bartoli said. The service lines his team gathers data on are made of materials that are already known by the water utilities. Bartoli’s team guesses the material based on the vibrations, then checks this against the utilities’ records.

The lab started testing out the technique on some of American Water’s pipes in Camden, New Jersey in 2018, Bartoli said. Now the research is part of a project by the Water Research Foundation to find the best methods of determining service line material. The partnership has allowed the team to do research on service lines in cities including Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Washington, D.C.

The Drexel researchers still need to validate their data and fine-tune the process they’re developing, before it can be deployed at scale.

“The idea is to make this … a no-brainer to do,” DeVitis said. “On the order of 100 bucks or something — similar to say, a lead test that you can just do from your faucet at home. We’re trying to bring it to the masses.”

A nationwide mandate to find lead pipes

If the Drexel team’s technique works, it could be in high demand.

Water utilities across the country need to make an initial inventory of service lines and the materials they’re made of by October 2024, under the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule.

“We have about 500,000 service lines, so it’s a pretty big effort,” said Adam Hendricks, who manages the Philadelphia Water Department’s applied research group.

Excavating all these pipes to determine their material would be expensive, Hendricks said.

“I think the low number is around $2,000 per service line,” Hendricks said. “So when you add up those costs for the number of unknowns we have, it quickly gets pretty high.”

In Philly, service lines are owned by the customer.

The Philadelphia Water Department estimates there are around 20,000 lead service lines in the city, mostly connected to older homes. But officials say they don’t know where exactly these are.

Digging up service lines is not the only way to determine their material. The Water Department has started its inventory by looking at existing construction records and using predictive modeling, Hendricks said.

When the Water Department replaces meters, as it’s currently doing throughout the city, officials can look at the part of the service line that runs from the curb into the house. Officials can examine and, with homeowner approval, replace the entire service line while doing main replacements. But in recent years, the Water Department has replaced less than 1% of its water mains each year.

“Our regulators really want us to know and have good, definitive records for both portions of the service line, which is where a technology like Drexel’s really comes into play,” Hendricks said.

A 2022 American Water Works Association study revealed that while mechanical excavation is considered the most accurate method for verifying service line material, it’s costly and time-consuming. Cheaper alternatives like using historical records and seeking data from customers, as Newark, Delaware is doing, come with their own challenges, from varied accuracy to low engagement. Emerging methods using sound or magnetic waves could have advantages, but require state approval and resources.

The Water Research Foundation project involving Drexel is testing using sound, stress waves, and x-rays for pipe identification. These three methods were on the Water Research Foundation’s “shortlist of most promising technologies” that hadn’t been fully developed, said CEO Peter Grevatt.

‘Assurance that you’re not going to be poisoned’

Philadelphia Water Department officials say they expect the EPA to eventually require utilities to replace all lead service lines.

Knowing where these lead pipes are is crucial, said Maurice Sampson, Eastern Pennsylvania director at the national nonprofit Clean Water Action — which pushed for the inventory requirement.

“We need to know where [the lead] is,” Sampson said. “Then we can make a real plan for getting rid of them. We can also get really focused on where the primary concern is.”

In Philadelphia, non-Hispanic Black children and children living in areas of North and West Philly have the highest rates of elevated blood lead levels. Kids can also be exposed to lead through paint and soil.

Since the 1990s, Philadelphia has treated its water with a chemical that coats the inside of pipes to help prevent lead from leaching in. Last year, the utility tested the water coming out of taps in around 100 homes with known lead services lines — and found lead levels met the EPA’s standard in 97% of these homes.

More lead than usual can get into water when pipes are shaken or banged due to nearby construction. Asked whether the Drexel experiment could have a similar effect, Bartoli said the water utilities are monitoring for this, but he does not anticipate a problem because the vibrations are “very small.”

Sampson says corrosion control treatment works, but he sees it as just a temporary solution.

Disasters like the lead crisis in Flint, Michigan — where officials failed to use corrosion control treatment after switching water sources in 2014 — show that as long as pipes are made of lead, there’s a risk that something can go wrong.

“If you want to have assurance that you’re not going to be poisoned, then you want to make sure there’s nothing in the line that might poison you,” Sampson said.

What to do if you have a lead service line

If you’re concerned you may have lead pipes, you can ask the Philadelphia Water Department to test your water for free. You can also test your own service line where it enters your home using just a coin and a magnet.

“We’re in an old city, and there are challenges that come along with that,” said Jerome Shabazz, executive director of the Overbrook Environmental Education Center. “Caution can go a long way.”

Shabazz also recommends at-home lead tests made by 3M, which he said can be used on pipes or painted surfaces.

If you find out that you have lead pipes, try not to use water that has sat in the pipes.

“The more it sits, the more the contamination is there,” Shabazz said.

The Water Department recommends running your water for 3 to 5 minutes before using it whenever you have not used the water in your home for at least 6 hours. You can also flush a toilet, take a shower, or run a washing machine to flush your pipes. Boiling water does not remove lead — and can in fact concentrate it.

The Water Department will replace lead service lines for free, with the homeowners’ approval, when replacing the water main on the block.

Eligible homeowners in Philly can also get zero-interest loans repayable over 60 months to replace lead service lines.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.