Changing the beat: Philly rappers take the violence out of drill music

Drill music, a subgenre of hip hop, has come under fire for graphic depictions of violence and criminal activity. Some Philadelphia artists are working to change the genre its

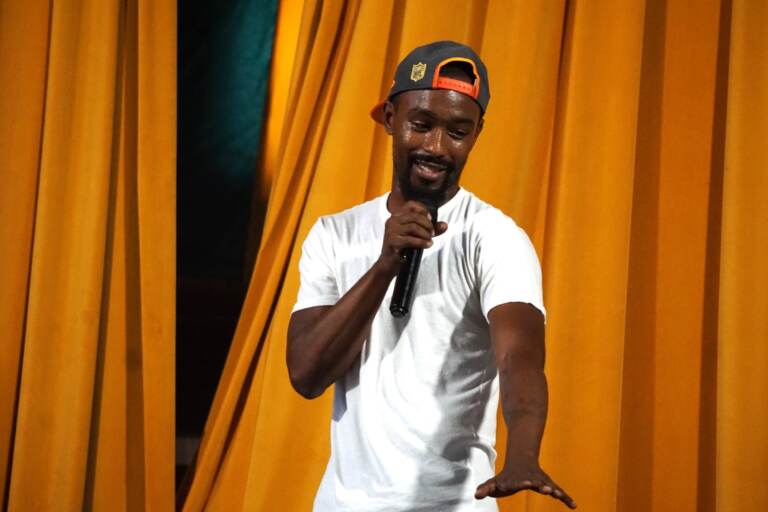

Darice Gardner, aka Paper$, performs at 'How Dope Are You?' (Sam Searles/WHYY)

This story is from Stop and Frisk, a podcast production from WHYY News and Temple University’s Logan Center for Urban Investigative Reporting

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

How do you feel about stop and frisk (and policing more broadly) as an answer to Philly’s gun violence crisis? Get in touch

In Episode 2 of “Stop and Frisk: Revisit or Resist” podcast, South Philadelphia High School teacher Armond James speaks to co-hosts Yvonne Latty and Sammy Caiola about depictions of violence in drill music. James shared his concerns for how drill music often glorifies violence. “It’s a whole underworld, this stuff going on and the kids are telling you about it in the class,” he said.

This past summer, as part of the gun violence prevention beat, WHYY covered the genre, exploring its origins in hip hop, the national and international criticism, and how some Philadelphia rappers are trying to change the music’s messaging to improve the city.

“Baby, welcome to the party

I’m a thot, get me lit

Gun on my hip

One in the head

Ten in the clip

Baby, baby, don’t trip

Just lower your tone

‘Cause you could get hit”

– ”Welcome To The Party” by Pop Smoke

Drill music, a subgenre of hip hop from Chicago’s South Side, emerged in the early 2010s. Strongly influenced by trap music from Atlanta, Georgia, drill uses lyrics that focus heavily on money, drug use, violence, and sex.

As drill music began to spread in popularity, so did the scrutiny: Drill was suddenly being used as evidence in court cases, rappers like the late Pop Smoke began putting disclaimers on music videos that the guns shown were props, and New York City Mayor Eric Adams decried the amount of drill music on the internet.

In Philadelphia, drill music has taken center stage in criminal trials, with a prominent case resulting in the 2018 resentencing of Ronald “Hollow Man” Thomas. Thomas had successfully appealed a murder charge in 2010, arguing that jurors in the original case made a biased decision based on his song lyrics.

On April 22, 2010, Thomas murdered 23-year-old Anwar Ashmore after the theft of a brick of cocaine. Both Thomas and Ashmore were members of Team A, drug dealers and rappers operating in the Strawberry Mansion section of North Philadelphia. Five months after Ashmore’s killing, Thomas’s mixtape “Ear Bleed” was released. Among the mixtape’s lyrics:

“Half a brick missing, and it’s one of my [N-word]

Can’t point fingers because I don’t know who did it

But soon as I find out, I swear that [N-word] finished”

Reimagining drill music

In the time since Thomas’ trial, Philadelphia artists and community advocates have been vocal about making an impact on the music scene without violence. Blackwell Community Alliance hosts a monthly competition called “How Dope Are You?” where performers vie for cash. The catch? The music, poetry, spoken word, or a combination thereof, cannot contain swear words or references to violence, drugs, or sex.

Artists like Darice Gardner, who uses the stage name Paper$, and Alonzo Good, who uses the stage name AKG, sign in to perform and give their music to the DJ. The rules, according to emcee Saj “Purple” Blackwell, are simple, and there are church ladies in the audience to make sure they’re followed. After each performance, the audience participates to see if there was a violation. “Did he talk about shooting up the block?” asks Purple. After hearing a chorus of “nos,” Purple asks, “Did he talk about shooting grandpa?” When enough “nos” have been accrued for every aspect of a given song, the contestant is officially in the running for a cut of $500.

Paper$, who successfully made it through the judging process, says he still uses drill as a genre of music, but is making it his own.

“Nowadays, I’m trying to change the narrative on drill music … I’m putting the knowledge into it. I’m going to change the narrative and not talk about guns and violence and stuff like that, but more about prosperity [and] making it to the top without having to be a product of my environment.”

AKG agrees, adding that parents are responsible for what their children listen to. “I went to the basketball court maybe two weeks ago, there [were] kids jumping around to drill music and they knew it word by word [and they were] little kids … we’re going to make music that’s going to help them and steer them in the right direction.”

Beyond performances, some Philadelphia artists, knowing they can draw attention, partner with community organizations to amplify resources. “Block by Block,” an event hosted by the City of Dreams Coalition in mid-August, brought performers and resources to the intersection of Broad Street and Erie Avenue.

Artist K. Walker said that drill music is a symptom of gun violence, not a cause.

“If anything is happening through drill music in Philadelphia, nine times out of 10, it was already like that. We’re talking about a city averaging 500 to 600 murders per year since the ‘90s,” Walker said. “So drill music didn’t do anything … I’d rather them go rap about it,” he said, “than be on the corner doing it because drill music — music, period, is keeping kids off the corner for a long amount of time … music is getting people off the street faster than college in Philly.”

Walker added that drill music, in his opinion, is targeted as a cause of gun violence because it’s easier to deal with than systemic issues like poverty.

“A drill beat is louder than the need to do a good cleanup in Frankfort and Northeast. A drill beat is louder than needing to go downtown and clean up some of the homeless people who are forced to commit crimes to eat. A drill beat is louder than a lot of stuff that you need to be paying attention to,” said Walker. “The music is influenced by the things they need to clean up first … What are we supposed to do? Just sit here and drown in it? How can you blame drill music but you don’t blame the city officials?”

While drill music hasn’t been used in many Philadelphia court cases, and some of the genre’s biggest stars have campaigned against the use of lyrics in trial, drill is still at the center of controversy. In Thomas’ case, even though the 2018 retrial began with the stipulation that no jurors would have heard “Ear Bleed,” he was convicted of murder again and sentenced to life in prison without parole.

During the final performance of “How Dope Are You?” Paper$ argued that the glorification of violence often heard in drill music is nothing to celebrate.

“I could talk about a gun. Yes, I’m gonna keep a gun on me, but at the end of the day, I’m not going to glorify the gun. Why glorify it? Why glorify what you have to protect yourself from a person that may be a killer?” said Paper$. “I lived that life, but I’m not going to sit up here and put it into rhymes. [There are] times I pause in freestyles and be like, ‘Oh no, I ain’t singing that.’ You have to be wise about the words that you’re putting out there.”

A quick search online for “Philadelphia,” “anti-violence,” and “music” yields dozens of results for artists, community groups, and funding for arts education. The Block by Block event by the City of Dreams Coalition boasted some 40 rappers, and “How Dope Are You?” another dozen. In October, Philadelphia artist ARSIN held the #PrayForPhillyChallenge to encourage young artists to rap about something positive over a beat he produced.

Collective responsibility and positivity were common themes among artists at both events.

“I don’t care how much music you put out [or] how phenomenal you might be or you might sound,” said Paper$. “At the end of the day, if you’re not pushing knowledge or gaining any type of perspective to make you a better person or make the world better, then you’re doing it for all the wrong reasons.”

Sam Searles is a Report for America corps member covering gun violence and prevention for WHYY News.

Stop and Frisk: Revisit or Resist

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.