Overbrook Elementary third graders are working to turn their asphalt schoolyard into a community green space

Overbrook students spend recess in a bare-bones concrete yard. Now, they’re working with Trust for Public Land to reimagine the space.

Overbrook's concert schoolyard (Celia Bernhardt/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

At West Philly’s Overbrook Elementary School, a group of third graders recently spent part of the morning outside in their asphalt schoolyard. Split into groups and holding printed maps of the space, they wandered around and brainstormed about how the space is used — and what it could become.

“Y’all, we could put a basketball court right there!” one student said excitedly.

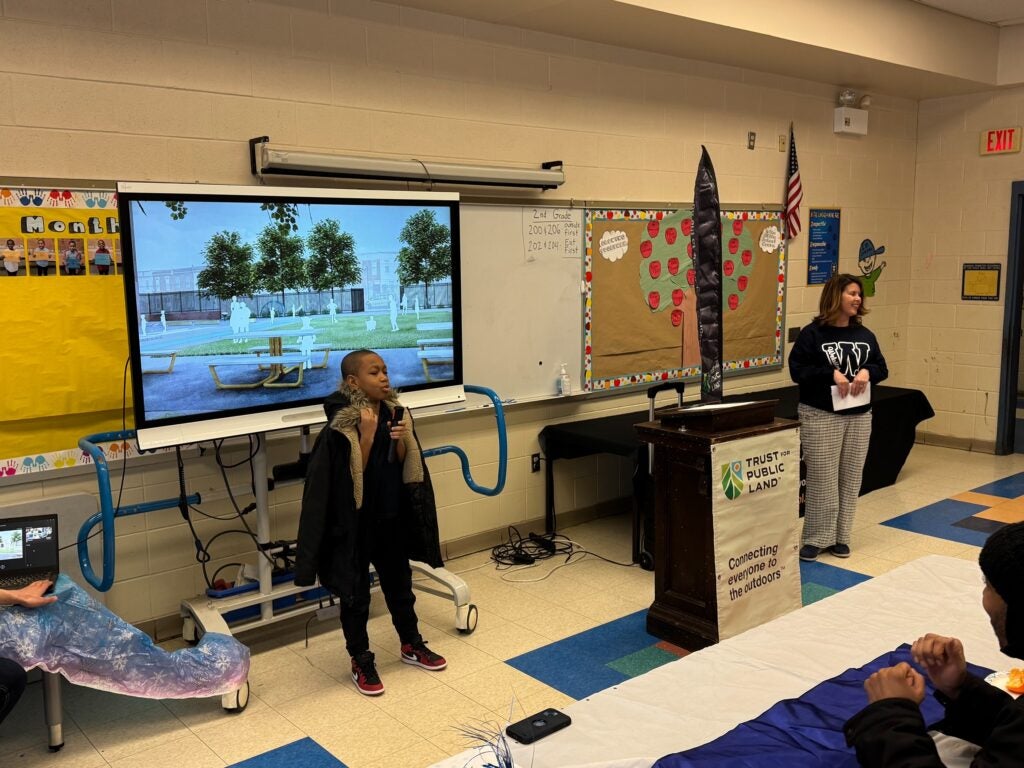

Overbrook is one of three Philly schools currently in the process of revamping their schoolyards with support from the Trust for Public Land, a nonprofit that works to create equitable access to public parks, green spaces and natural lands across the United States. TPL’s work focuses on low-income neighborhoods that have less access to green spaces. The organization coordinates with school districts to build new, climate-friendly schoolyards that serve students and the surrounding neighborhood during after school hours. But, instead of leaving the renovation process entirely up to an architect, TPL’s participatory design program gives kids the reins. TPL has already revamped 15 schoolyards in Philadelphia, including Alain Locke and Benjamin Franklin Elementary, and hundreds more nationwide.

How TPL works with school children to design their yards

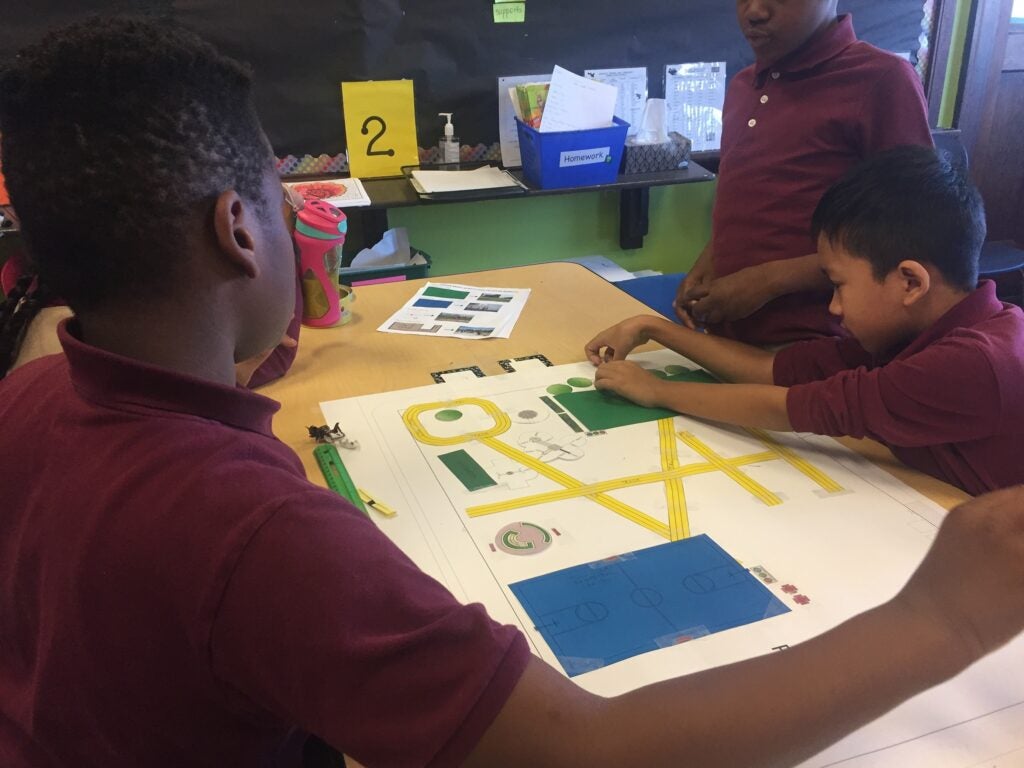

In weekly meetings over the course of three months, TPL staff members guide students in learning and practicing design principles. Students collect community input and work together to create a new vision for the schoolyard. Once the design is finalized, TPL and their partners raise funds, develop architectural blueprints and oversee the permitting and construction process. Community schoolyards can cost between $750,000 to more than $2 million; most of that money comes through Philadelphia’s water department, according to TPL.

‘Important tool for public health’

Paul Jones, a professor of psychological studies in education at Temple University, said that schoolyards that promote more physical activity with increased tree shade and play equipment can be an important tool for public health. Studies show that these open spaces in nonwhite and low-income communities are smaller, more crowded, and fewer and farther in between when compared to wealthier neighborhoods.

“When we’re talking about Black and brown communities around Philadelphia, we’re talking about major health disparities in terms of rates of disease and illness, we’re talking about disparities in access to quality health care,” Jones said. “If we think about preventative models of health and wellness, promoting physical activities is sort of rule number one.”

Owen Franklin, TPL’s Pennsylvania state director, said that recess in these green spaces may also help with concentration, behavior and attendance.

“[There are] tremendous benefits that we see in students being able to exercise during the day, and be outside, and then come back into the school ready to learn,” he said.

Franklin said a southwest Philly school saw their suspension rates — which had most frequently occurred at recess and dismissal — drop to zero after the completion of their community schoolyard. He attributes the change to the new playground design, which facilitates safer play and less student conflict.

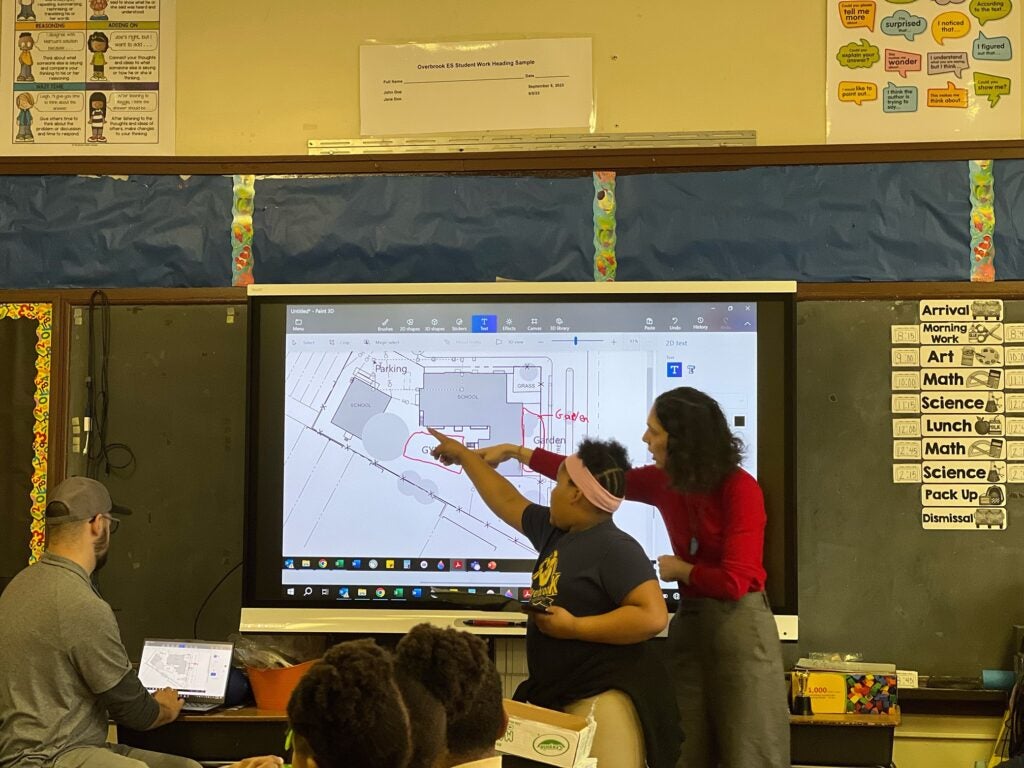

On a recent morning, students working with TPL came one by one to the front of the class, where the smartboard displayed a blank version of the schoolyard map they had just used. The students described which spots in the asphalt yard are used for playing freeze tag, or for sitting down and relaxing. They also marked the gym zone, and the expanse in front of the entrance where students line up when it’s time to go back inside. As students pointed to the different spots, a TPL staff member updated the map with new labels and notes.

Some students disagreed with each other on where certain sports are played. An instructor reminded them to consider how the older and younger kids use the space and how it could be different from how they do things.

Caleb, a 9-year-old in Overbrook’s third grade class of student designers, said he feels happy during the weekly sessions with TPL.

“My favorite part is designing the schoolyard and figuring out what to put in it,” he said. “I hope it kind of looks like Tustin Park … and kind of looks like Lemon Hill Park.”

Most Overbrook students are drawn from the surrounding neighborhoods. 94% of students in the school are Black, and 100% of the student body is categorized as economically disadvantaged. The K-8 school does not have a gymnasium, or an auditorium. Principal Kenneth Glover said he was excited that TPL was open to building an outdoor stage as part of the playground upgrades. Most importantly, though, he’s looking forward to the students having a safer space to play.

“As you can see, it’s kind of a concrete jungle out there,” Glover said, motioning to the schoolyard. “We make things work. But they also deserve a place to play.”

When it rains or there is inclement weather, the students have to be rushed back up to the classroom.

Glover said the students are picking up skills that complement what is being taught in the classrooms.

“It’s helping them advocate for themselves,” Glover said about the design process. “The communication piece is needed.”

Education experts agree that when students are able to exercise their agency in school, they become more engaged.

“Giving them the opportunities to actually have a say in what they do with all the information they’re collecting, and to choose the equipment … and then actually, in real life, show that their voice mattered, is incredibly empowering,” global education expert Rebecca Winthrop said.

The engagement that these creative activities generate can even “spill over” into their experience in other classes, according to Winthrop.

“Having agency, being the author of your own life, even if it starts in small, small ways, is just an incredibly positive, life-affirming experience for kids,” Winthrop added.

Franklin said kids learn to grapple with real, practical concerns as they work towards that end result.

“These students are being asked to make decisions that impact not only themselves, but their fellow students and the community,” Franklin said. “They’re speaking for other people and they learn about the responsibility and the humility that comes with that role.”

At the same time, Franklin said, they’re also learning to make trade-offs — navigating budget limitations and deciding what should be prioritized under finite resources.

From start to finish, a playground redesign can take about two years. That’s why the program is intentionally aimed at grades who have a few more years to go before graduating. At Overbrook, third grade student designers will get to enjoy the fruits of their work.

“The students are seeing that their voice and their opinions can change the world,” Franklin said. “That what they envision can become real.”

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series that explores the impact of creativity on student learning and success. WHYY and this series are supported by the Marrazzo Family Foundation, a foundation focused on fostering creativity in Philadelphia youth, which is led by Ellie and Jeffrey Marrazzo. WHYY News produces independent, fact-based news content for audiences in Greater Philadelphia, Delaware and South Jersey.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.