Call it a comeback: A paternal sculpture destroyed by the Delaware River gets a second life at Penn State Abington

When the giant acrylic bust was erected, Miguel Antonio Horn’s father was undergoing cancer treatment and his survival was not guaranteed. It’s now revived, scars and all.

Listen 1:25

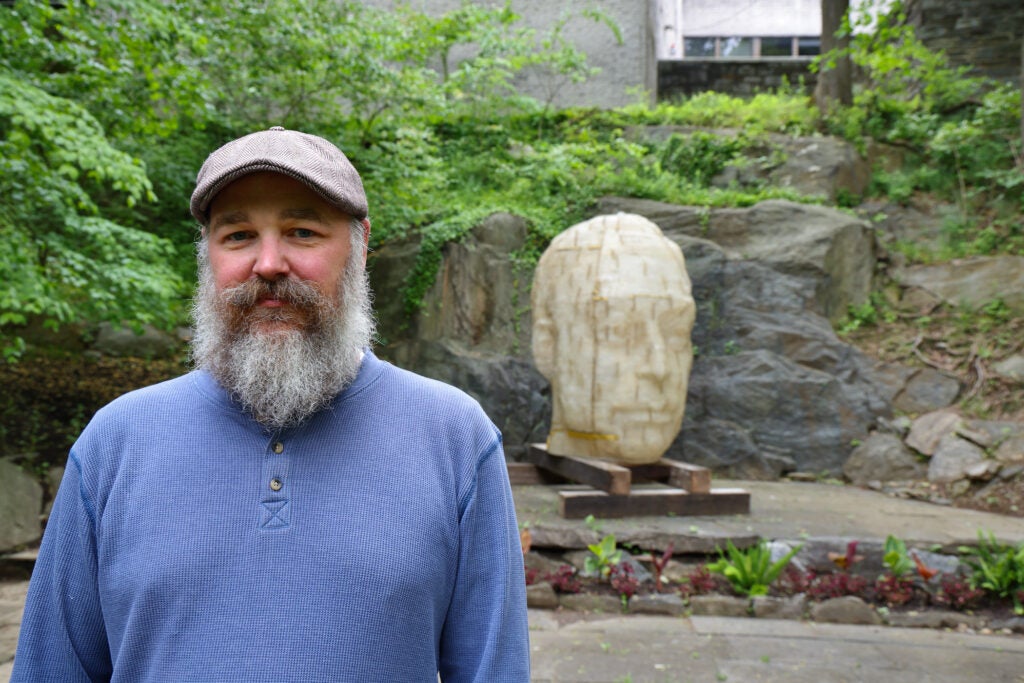

Miguel Antonio Horn's sculpture of his father's head, intended to be viewed through the rising and falling tides of the Delaware River, has been restored and installed against a granite backdrop on the grounds of Penn State Abington campus. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

When artist Miguel Antonio Horn fished a large sculpture of his father out of the Delaware River in 2019, he thought: “I’m done with it.”

Just weeks after he had installed the enormous translucent acrylic bust, called “Abu” after his father, in the marina outside the Independence Seaport Museum as part of an aquatic group exhibition “Flow,” a sudden nor’easter ripped it apart.

After pulling his father’s head out in pieces partly buried in river silt, Horn was demoralized.

“I think it was in the wake of that trauma, seeing this piece completely destroyed,” he said. “As I looked through all the pieces, it became pretty clear that structurally it was compromised in a way that would require rebuilding it entirely.”

Since then, Horn debuted an even more ambitious public art piece, ContraFuerte, a skyway bridge over an alleyway near the Reading Terminal that appears to be held up by groups of figures clinging to the sides of the buildings. That piece, appearing to be held aloft by magical engineering, became a global phenomenon on social media.

Now, with some encouragement and funding from Penn State Abington, “Abu” has been reconstituted on the leafy suburban campus. It has been erected in front of a small stone cliff sometimes used as an amphitheater.

“It was so successful in the ‘Flow’ exhibition. I felt it was the strongest piece there,” said John Thompson, director of Penn State Abington’s art gallery. “It had so much to say and so much impact and presence that I just kind of wanted to see it back.”

“Abu” still bears the scars from its previous life. Horn gilded those scars with gold leaf in a manner similar to kintsugi, the traditional Japanese pottery repair method that highlights and honors the life of the object.

“I had a couple people, like John, reach out and say this is a way more profound piece because of what’s happened to it,” Horn said. “It’s all about loss and it’s all about grief and personal connection. That the piece suffered this trauma makes it that much more real.”

Thompson says he has a modest budget to run the campus art gallery, about $5,000 annually. He devoted most of that, $4,000, to the repair and installation of “Abu.”

The bust was originally designed to be partially submerged in river water. As the tide would rise, Horn’s father’s face was obscured, and revealed again when it lowered. Back then, in 2019, Alexander Horn was undergoing cancer treatment and his survival was not guaranteed. The sculpture’s periodic appearance and disappearance reflected a father who could sometimes feel absent, coupled with the looming threat of not being there at all.

The piece is made with a skin of ribbed acrylic over an internal support structure. The clear plastic gave “Abu” a ghostly glow. Initially it worked as designed, until overwhelmed by the power of water.

“There was a lot of ego, trying to master and control the elements of a river,” Horn said. “It was also me trying to stop time.”

Since then, Horn’s father’s health has stabilized, as has his acrylic doppelganger. “Abu” is mounted on stacked wooden beams against a background of stone. The ribbed contours of the bust play off the striations of the granite. The gold leaf scars glimmer in sunlight.

The sculpture is still and quiet, no longer animated by the river, but “Abu” still responds to time — just on a much longer cycle. Instead of playing peek-a-boo with the tide, it responds to the seasonal changes of the foliage surrounding it.

“There’s a language of memorial that it is something that you would see in Laurel Hill Cemetery: this big stone backdrop and this monumental head,” said Horn, who still sees his very much alive father every week. “I feel like it kind of embodies this connection with my dad.”

“Abu” will be installed at Penn State Abington for a year, likely longer. Horn has wired it with automated LED lights, so it glows from within nightly.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.