Library Company displays patient memoirs from 19th-century asylums

Patient memoirs of 19th-century asylums tell the good, the bad, and the ugly from the early days of institutional mental health treatment.

Before and after photos show women who were given the rest cure for hysteria in the late 1800s. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

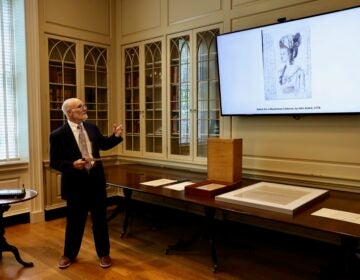

Curators at the Library Company of Philadelphia had started to work on an exhibition about the history of mental health treatment a few years ago, before the world was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the shutdowns it triggered.

Studies show there have been an increase in mental health problems in the last two years, particularly among teenagers.

“We did not know that it would be quite as relevant to folks today,” said Rachel D’Agostino, curator of printed books. “We really feel it’s very important for people to understand the history of mental health treatments, to see what went wrong when the intentions were good.”

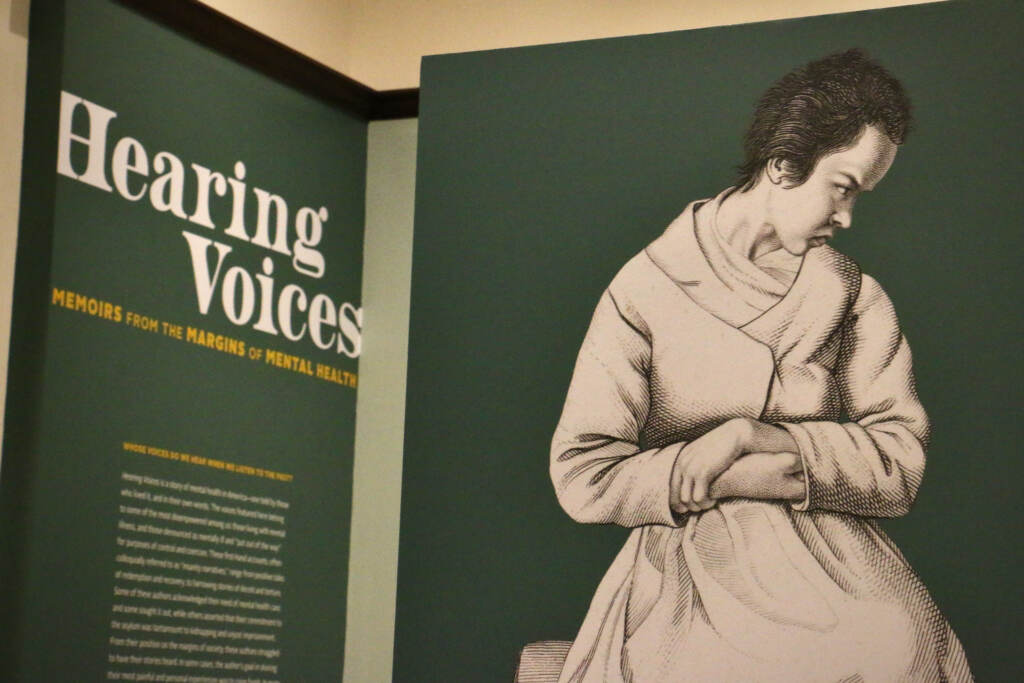

The exhibition “Hearing Voices: Memoirs from the Margins of Mental Health” is based largely on first-person experiences written by people who underwent treatment inside 19th-century asylums.

Many of the books sought to reform what was seen as a flawed system, with provocative titles: “15 Years in Hell,” “Eight and One-Half Years in Hell,” “Ten Years and Ten Months in Lunatic Asylums in Different States,” and “A Mad World and Its Inhabitants”.

Large-scale, public institutions designed for mental health treatment were first built in the 19th century, along with procedures such as the “moral treatment,” which involved fresh air, freedom of movement, and compassionate care.

One of the pioneering doctors for moral treatment was Dr. Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia, with the Pennsylvania Hospital. In the mid-19th century the hospital built the Pennsylvania Asylum for the Insane, or Kirkbride’s Hospital, in what was then a largely undeveloped and verdant West Philadelphia.

“When all of that went to plan, because there was enough funding and informed participants, it worked really well. There were lovely, lovely asylums,” said D’Agostino. “By and large, things did not go according to plan and there were many reasons for that.”

The exhibition goes into detail about why asylums went wrong.

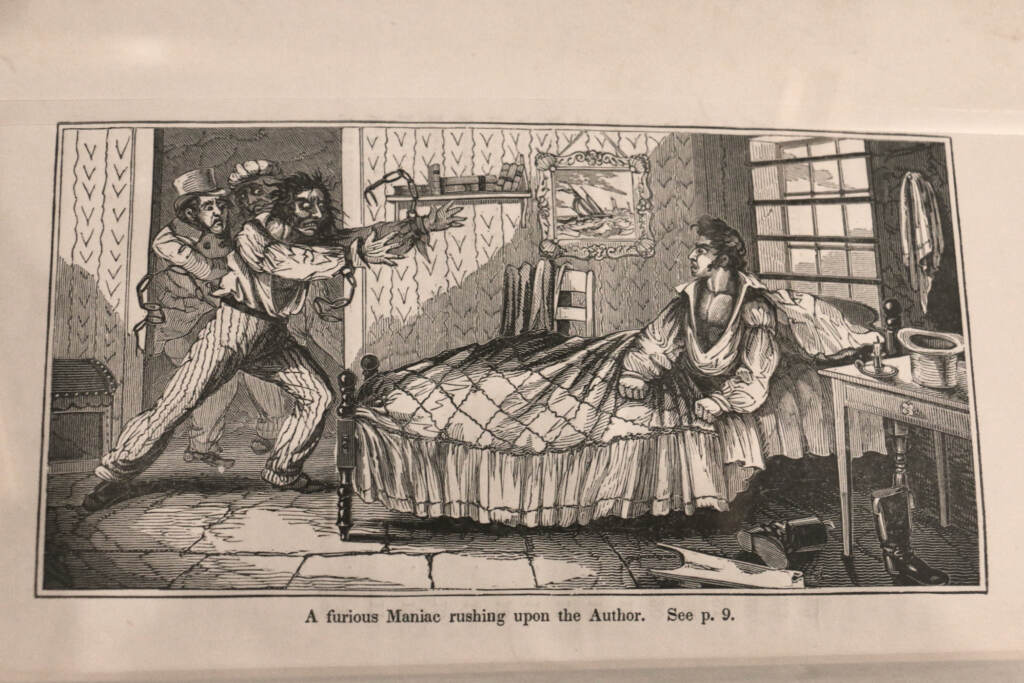

One person for whom institutionalization worked was John Derby, who wrote about it in prose, “Scenes in a Mad-House,” and in poetry, “Musings of a Recluse.”

“John Derby was a politician who didn’t do very well in politics,” said assistant curator Sophia Dahab. “He ended up losing an election, couldn’t go back to his former job, and suffered some sort of mental breakdown which led to his treatment at McLean [Asylum for the Insane] before being moved to a private retreat.”

At McLean, in what is now Somerville, Massachusetts, Derby wrote about the sometimes disturbing behaviors of patients, including — but not identifying — himself, written in the third person. He then moved to a private retreat run by Dr. Nehemiah Cutter in the much more rural and remote town of Pepperell.

“It’s an interesting comparison to the treatment that he was receiving at McLean Asylum versus the Cutter retreat,” said Dahab. “The state-run institution, and then this smaller private retreat where he received wonderful care that ended up saving his life.”

Others were not so lucky, particularly women.

Dahab said diagnoses of mental health conditions were vague, at best, and sometimes entirely fabricated by doctors or family members.

“Unfortunately the language that we use to describe mental illness has changed so much. They refer to things like monomania, moral insanity, hysteria. What is that?” she said. “The women in this show, a lot of them were diagnosed with hysteria or something similar, if anything at all. A lot of them were sent to asylums because they had differing religious views from those with their family, or they had financial issues and became a burden to their families.”

Women were often given the “rest cure,” which “Hidden Voices” describes as anything but. Patients were often force-fed against their will and strictly confined to their beds for days or weeks.

The cure was developed by Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, who advocated recovery through the “absence of all possible use of brain and body.” He appears as an antagonist in “The Yellow Wallpaper,” an 1892 short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who fictionalized her personal experience as a patient of Mitchell, describing her powerlessness as a patient. The story was adopted by feminists and is now being made into a movie.

The Library Company asked artist Tiffany Weiser to recreate the wallpaper of the title. One wall of the exhibition swirls with the ornate patterning, evoking the disorientation and hallucination described by the trapped protagonist in the story.

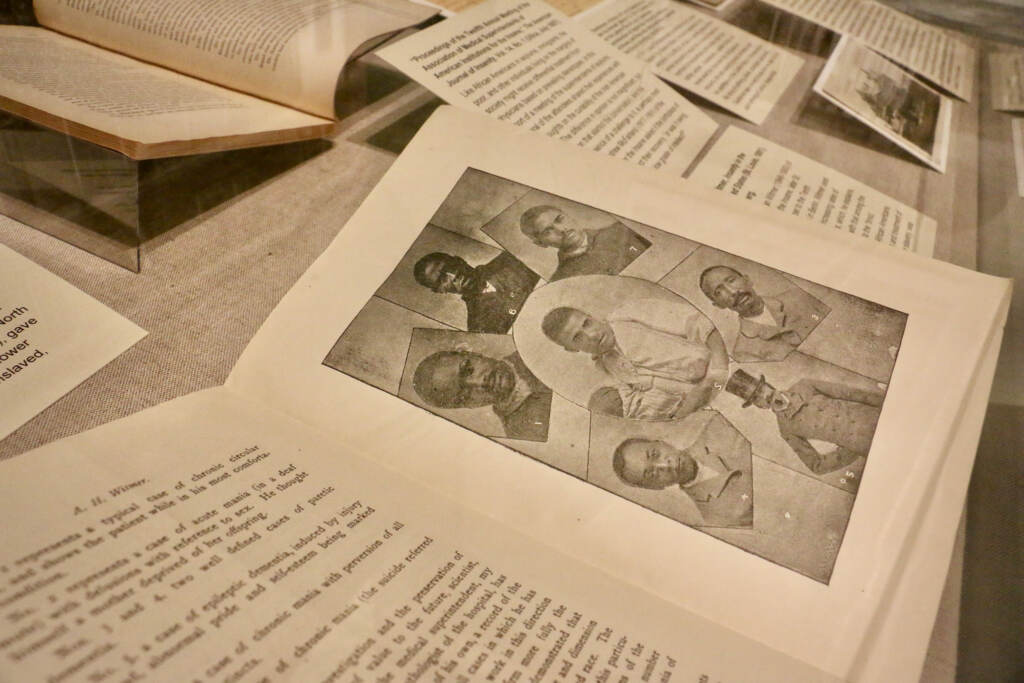

D’Agostino also included a section in the exhibition of Black and Native American people who were not able to record their own experiences.

“This was an emotionally challenging part of the exhibition to curate,” she said.

A flawed U.S. Census survey in 1840 miscategorized high numbers of Black people as mentally unwell, identifying them as “insane” or “idiots.”

That census was later dismissed as “totally unworthy of credit,” but nevertheless it fed a widespread notion that freedom from slavery could trigger mental illness in the Black population.

The Library Company could not find first-person accounts from Black people who were mis-identified as “insane,” instead using mostly census and legal documents to show how it happened.

D’Agostino also included the only mental health institution built specifically for Native Americans, the Canton Indian Insane Asylum, which opened in 1903 in Canton, South Dakota.

Also called Hiawatha, it operated for 30 years, in which time 350 people were held there, and 121 died.

Many Native Americans were sent there with no mental health diagnosis at all.

“There were a number of children who were at Hiawatha and their prospects were not good,” said D’Agostino. “If you entered Hiawatha, it was unlikely that you would leave. And if you did, it was likely that you left through death.”

She said holding patients in Canton until they died was by design, as the superintendent did not want to take on new patients. So he never let them go.

Hiawatha closed in 1934 and was demolished in the 1940s, but its cemetery, with 121 graves, still exists. It is now contained inside a municipal golf course, separated from players by a split-rail fence.

D’Agostino admits the story of Hiawatha is “disgusting to hear,” but necessary to include in the complicated history of mental health treatment.

“We’re at this stage in our history in the United States, where we are dealing with the repercussions of deinstitutionalization, which we see on our streets every day,” she said, referring to the movement since the mid-20th century to close residential treatment institutions.

“It’s really important to look at the history and to know that not every idea from the past was a bad one, but seeing where things went wrong to avoid those same pitfalls,” she said.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.