Essential, unemployed, overstretched: How the COVID economy crashed on women

Some call it the “triple whammy.” In Pennsylvania, as in the rest of the country, working women have faced unique hardship due to the pandemic.

Listen 5:03

Catherine Fortune De Sormeaux is a certified nursing assistant who had her hours cut during the pandemic. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the coronavirus and vaccines?

Some call it the “triple whammy.” Others, the “one-two-three punch and a kick.” In Pennsylvania, as in the rest of the country, working women have faced unique precarity and hardship due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Pamela Kichman, 27, of New Cumberland, lost her job at a warehouse after going through a half-dozen babysitters in as many months.

Catherine Fortune De Sormeaux, 63, of West Philadelphia, saw her hours drop doing home-based care work as her clientele became fearful of coronavirus.

Dr. Janet Cruz, 36, of Havertown, started working during odd hours — scheduling meetings before 7 a.m. — to fit them around her children’s schedules.

As the coronavirus pandemic turns one, researchers have found women have lost decades of economic progress, but some have also found a new voice in advocating for better family and work policies.

Women make up nearly two-thirds of the essential workforce in the commonwealth, according to an analysis by the Keystone Research Center. That is likely due to the number of health care jobs in the state, said Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center director Marc Stier.

Many in essential fields, such as food production, health care, and transportation, suddenly had more to do than ever — with less support.

Kichman said she was caught off guard by the pandemic. In March 2020, the Cumberland County single mother was putting in long hours at Syncreon, a logistics company that fulfilled orders for Apple in its central Pennsylvania warehouses.

It wasn’t until she stopped at a grocery store and saw lines of people with carts filled to the brim that she realized something was afoot.

“I’m like, ‘Why is everybody buying this stuff?’ They were like, ‘Do you watch the news?’ And I was like, ‘I work too much to watch the news,’” she said.

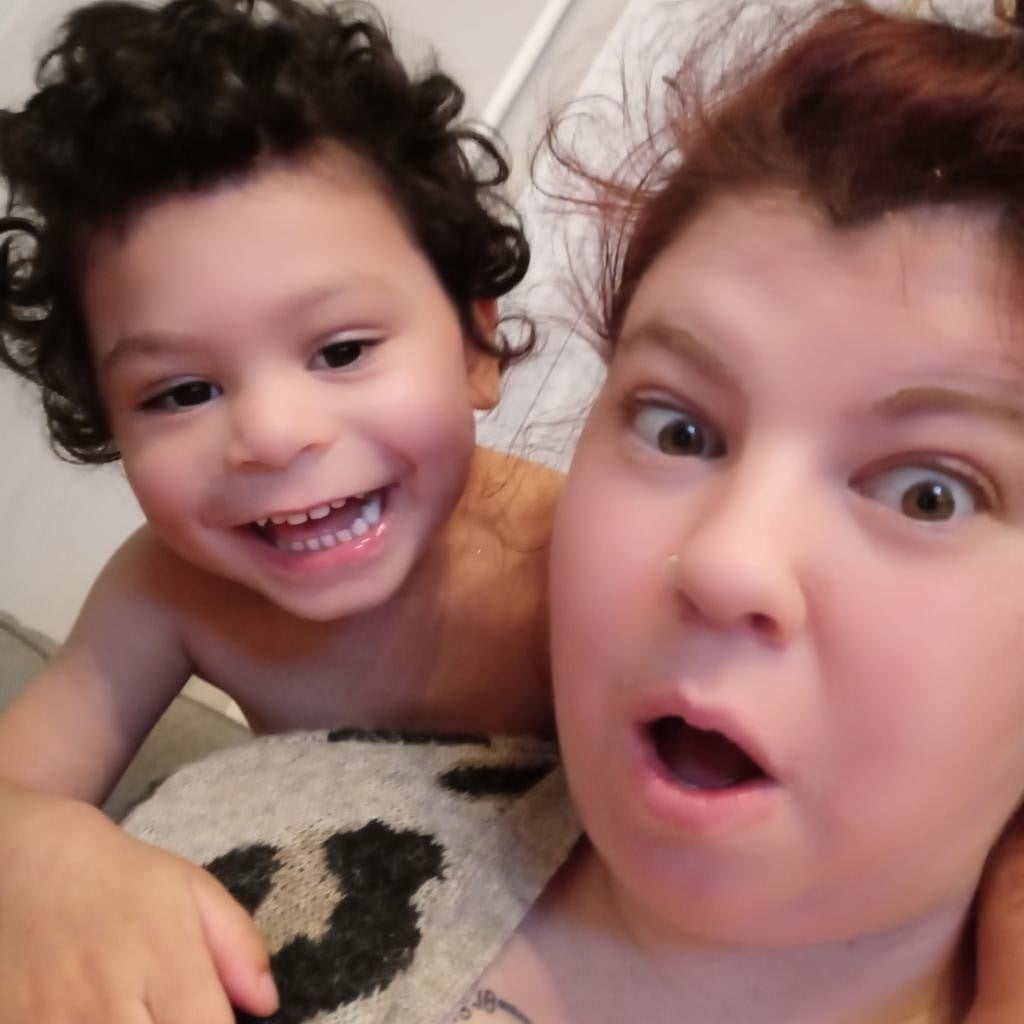

Instead of shutting down, her warehouse only got busier, picking up orders that could no longer be fulfilled abroad. Kichman supports her 2-year-old son, Avery, and needed someone to watch him while she worked picking and packaging products. She says the woman who ran the in-home day care where she sent him to has an autoimmune disease and quit watching her son.

So, during the first six months of the pandemic, she leaned on a rotating cast of friends and family members, but each one eventually stopped being able to care for Avery due to concerns for their health.

“I literally tried to exhaust every option possible,” said Kichman.

‘Didn’t want to show how much I was struggling’

Dr. Janet Cruz saw her responsibilities expand dramatically due to the pandemic. As the medical director of Drexel University’s Student Health Center, her job blossomed to include managing a public health emergency.

At the same time, her 7-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter needed more care and attention, and Cruz could no longer tap extended family to pitch in.

“Initially, I didn’t want to show how much I was struggling,” she said. She and her husband split child care, but Cruz was still going to the office working with high-risk patients, which made planning hard. Any cough, headache, or sore throat sent the whole family into lockdown mode.

Women are much more likely than men to stop work due to displaced child care duties as schools and day cares shut down, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

In Kichman’s case, it cost her her job. Each time she called out if a babysitter could not come, she got a strike. At Syncreon, she said, too many strikes and you’re out.

“I feel like people just say, ‘Oh, well, they just lost day care.’ Like, that’s nothing … But they don’t actually realize how big of a difference it has made. When you’re a single parent, like you could risk losing everything,” she said.

She became unemployed in September 2020, and survived on her savings and credit cards, before securing jobless benefits in the new year.

In addition to child care woes, some women lost work because they are over-represented in service sector jobs that shut down during pandemic.

Certified nursing assistant Catherine Fortune De Sormeaux spent more than a decade working in people’s homes before COVID-19 struck. Suddenly, she said, there was distrust and fear on both sides.

“The clients didn’t want us to come, and we were afraid to go into their homes,” she said.

Fortune De Sormeaux cut back on expenses and hunkered down. “I was really depressed, because I wasn’t sure what would be the income.”

The disproportionate effects on women during the pandemic have sent their economic progress back in time.

“Women’s labor force participation has been stuck at 1980s levels for nearly a year now,” said Julie Kashen, senior fellow and director for women’s economic justice at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank. Nationally, around 5 million women have lost their jobs.

Those losses are also not spread evenly. A report this year from the Federal Reserve of Philadelphia broke down the ways race, gender, and education all factored into job loss. Across Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, the people who saw the biggest declines in employment in the last year were Black men, Black women, and Hispanic women with no more than a high school diploma.

The effects, while more severe for women on the lower-economic end of the spectrum, extend to white collar work as well.

“It’s definitely hit us harder,” said Dr. Maya Bass, a family medicine physician in Center City Philadelphia. Instead of going to conferences and applying for leadership roles, she said, the pandemic has caused many women she knows “to take a step back.” She said she worried about losing a generation of mentors and leaders who would otherwise be there in the future.

“If we don’t all keep pushing forward, you don’t have the person who is in the higher-up level who can reach back their hand to help you up,” she said.

‘Priceless human beings’

Investments are being made to try to stop this slide, and some more family-friendly pandemic policies could stick around.

Panic over the harm caused to the child care industry led to a large investment in the most recent stimulus bill, the American Rescue Plan Act. Without that money, the Center for American Progress predicted 4.5 million child care slots could vanish due to the pandemic.

In the same law, lawmakers expanded the child tax credit, which will give parents $300 per month for each child under six and $250 monthly for children under 18 — through 2021. Those payments begin to decrease for individual filers who make more than $75,000 a year or couples who make more than $150,000.

Kashen, with the Century Foundation, said this change “will make a huge difference for supporting parents to pay for the high cost of raising a child, which includes everything from housing to food to school supplies to mental health supports.”

She hopes this direct aid and other supports that have started during the pandemic will become permanent.

“Once you see that something’s in place and that it works and that the sky isn’t falling, that can actually start to change cultural perceptions,” she said.

For some, the stress of the pandemic has strengthened long-held convictions.

Fortune de Sormeaux said she believes that there should be a path to citizenship for domestic workers. Originally from Trinidad and Tobago, Fortune de Sormeaux received her green card through family sponsorship, but knows many in her field do not have that option. She watched undocumented peers struggle through much of the last year without access to government aid.

“We are priceless human beings,” she said.

Others see hope in direct support, like the payments from the federal government that have been used to prop up families and individuals during the pandemic.

“I think single moms should get money … they need to start actual programs for single moms based on income,” Kichman said. She routinely spent up to $1,500 a month on child care, a very significant portion of her income, and has tried repeatedly without success to get one of the state’s subsidized day care slots.

Advocates say raising the minimum wage would also help bridge racial and gender inequities exposed by the pandemic. In Pa., the minimum wage has been $7.25 since 2009.

“About 34% of women would get a higher wage if the minimum wage were $15 in Pennsylvania,” said Marc Stier, of PBPC. “That’s about 12 points more than it is for men.”

While dropped from the most recent stimulus bill, there are attempts to raise the minimum wage at both the federal and state level.

Working moms who have been able to keep their jobs credit flexible policies for making that possible. Dr. Janet Cruz said she exploded her normal schedule to be able to get things done amid the pandemic. Meetings start before her kids wake up, and work continues after they go to sleep.

To get to that point, she said she had to overcome some of her own fears. Cruz remembers the first time she decided not to try to shoo her daughter away during a work Zoom meeting, and instead brought the 4-year-old into the frame.

“I really had to check my own guilt and my own feelings of inadequacy,” she said.

By first acknowledging to herself that she needed help — such as more support to take on more responsibility and flexible scheduling — she became more comfortable making requests to her bosses.

Other changes, such as the proliferation of telemedicine, also allowed her to spend more time with her kids, something she hopes does not go away any time soon.

“I feel like there is more support for the home life now,” Cruz said.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Get more Pennsylvania stories that matter

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)