Displaced Iranian artist re-creates her heritage in exhibit in Princeton

When Samira Abbassy was 2, her family moved from Iran to Britain, and ever since she has struggled to understand the culture of her parents. The artist, trained in the West, calls herself a “fictional historian,” reinterpreting her homeland. “I found I knew little of what this culture really was,” she says, in attempting to understand her Arab-Iranian heritage. “Once I sensed only the unease of being a non-white in a white society; now I feel unease on both sides of the cultural divides.”

In “Narratives: Hearts, Minds & Mythologies,” on view at Princeton University’s Bernstein Gallery in Robertson Hall through Aug. 13, the artist explores both her own personal mythologies and those shared with others.

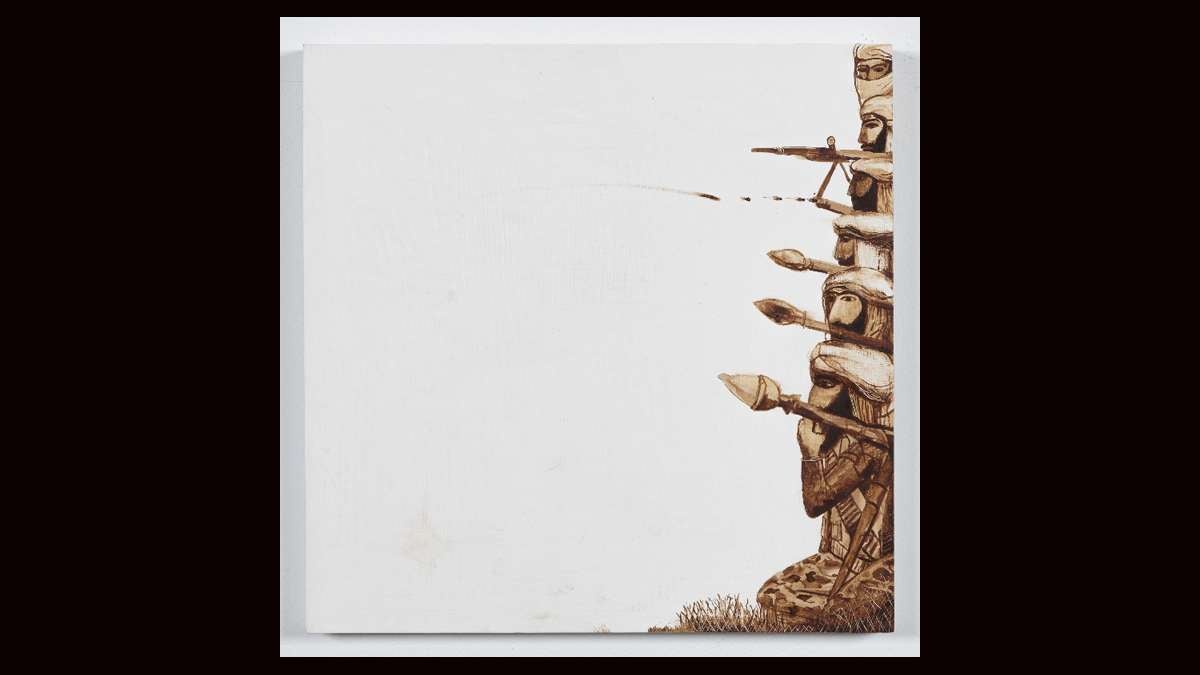

The Eternal War series focuses on the battlefield with a series of delicate sepia drawings, recalling Goya’s “Disasters of War,” considered one of the most significant works of anti war art. Abbassy bases the format on various “Shahnameh” (Book of Kings) manuscripts from the 15th century that illustrated epic poems, written in Farsi documenting the invasions of the Persian Empire. It presents a repetitive cycle of war, genocide, ethnic cleansing, occupation and exile. Older empires are obliterated and overlaid by new empires that bring their own cultures, histories and mythologies.

Abbassy examines the crusades and the cult of martyrdom in Shia Islam, using it to tell the story of contemporary battles in the Middle East. The Battle of Karbala was the first great battle in Islam and defined the split between the Shia and Sunni sects, she said. “Contemporary war vernacular defines the idea of victory as winning hearts and minds…a martyr becomes a suicide bomber and martyrdom translates as terrorism.”

In these panes we see heads roll, literally. A warrior impales himself with a spear. Horses trample where flowers bloom over heads in the ground.

Contemporary warriors who have dropped from a helicopter aim their weapons at the traces of an Islamic culture – seen in the curlicues of an arch, a turbaned figure with a gun on the ground, another turbaned figure on a TV amid rubble. Aircraft crashes to the ground in a smoldering flame, a soldier in camo gear gets his head blown off, and on the other end of the panel, warriors in turbans are at the ready with spears.

In “Osama Watches Himself on TV,” the face on the TV looks like the face of Osama we’ve seen, but the figure in the foreground, with a beard and turban, is made up of many faces, including a female.

The imagery can be unrelenting. Just when you think it might let up as you catch a glimpse of color, a mother in a pretty red dress, seated in a polka dotted red chair as she holds her small children, you realize she’s facing a figure in another chair who morphs from male to female behind a gossamer drape. It is titled “Mother of Silences, Seer of the Unseen.”

Born in Ahwaz, Iran, in 1965, Abbassy moved to London as a child. In 1988 she moved to New York to help set up the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts Studio Center, where she continues to maintain a studio and be a board member. Upon arriving in New York she felt alone, displaced and isolated. She creates an imaginary world in her artwork, blending cultural traditions – Indian, Persian, Tibetan, Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist – to develop her own visual vocabulary.

“Butterfly Burka” is a work in ink and collage in which we see a woman in the hijab, an opening torn through where the eyes should be, and butterfly wings emerging at her back. Has her spirit morphed into a member of the Lepidoptera family? Many of Abbassy’s female figures wear a long blue patterned dress, suggesting chastity. Here we see one with four legs, two of which are ensnared with rope. Six little heads encircle her face, like a headband, and behind her rages a fire under a twinkling sky, in the same pattern as her dress.

“Lamentation,” oil on gesso panel, seems of a similar ilk, with four women in burkas, one of which is blue. Behind them, a car is in flame, and 10 heads on the ground look to the women, waiting for something. An explanation?

“I use self portraiture as a way of examining and defining myself in a constantly shifting cultural context as well as a means of showing the link between the psychic, the biological and autobiographical self,” said Abbassy. “Seemingly specific, the figures are actually archetypal, not literally ‘my’ self. They are ‘the self’ from inside out; how it feels to be me, or more to the point, how it feels to be human. Their specific identities help uncover elements of a more universal self.”

________________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.