‘Art is part of culture’: How integrating arts is powering academic and emotional growth in Delaware classrooms

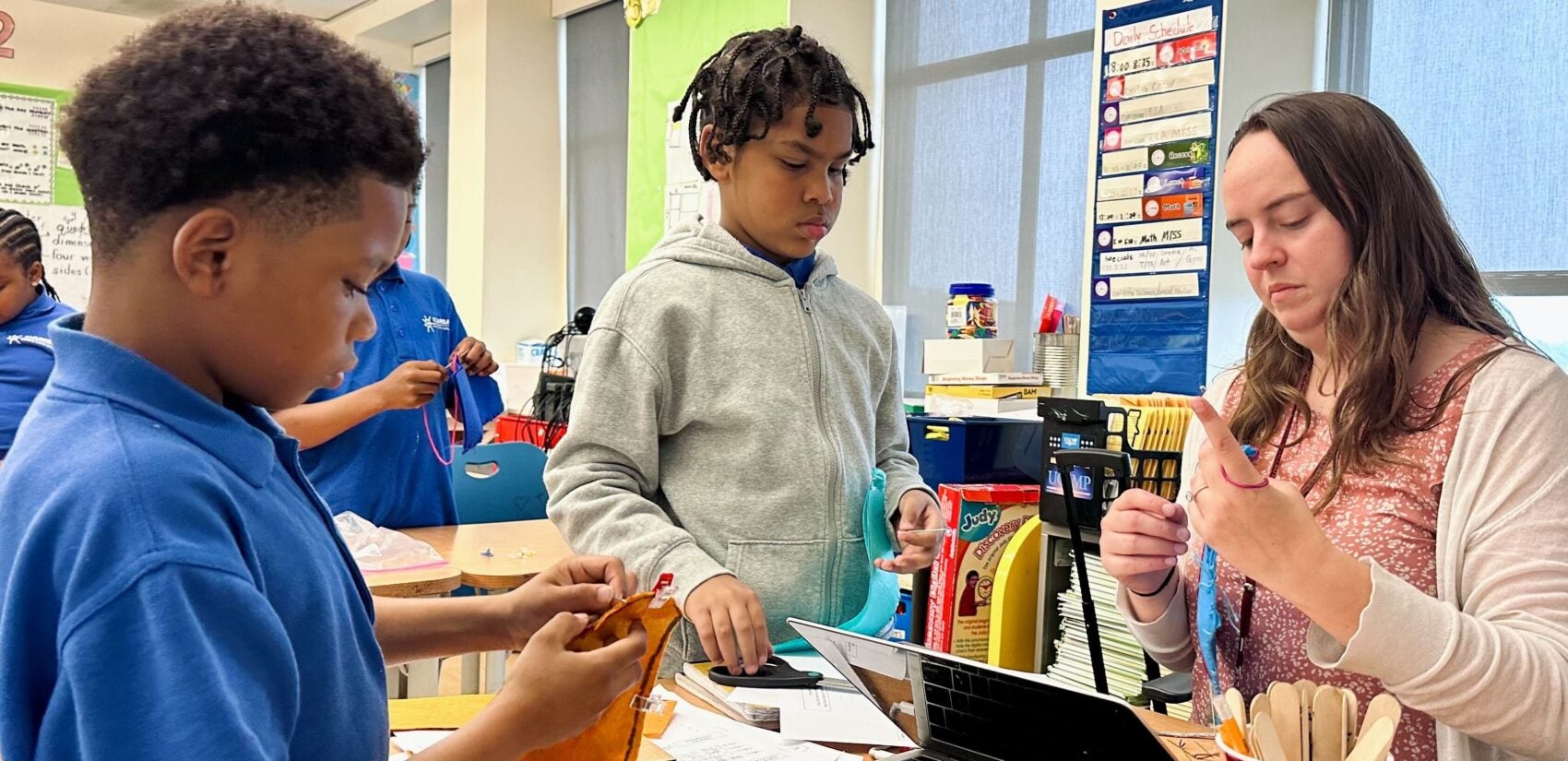

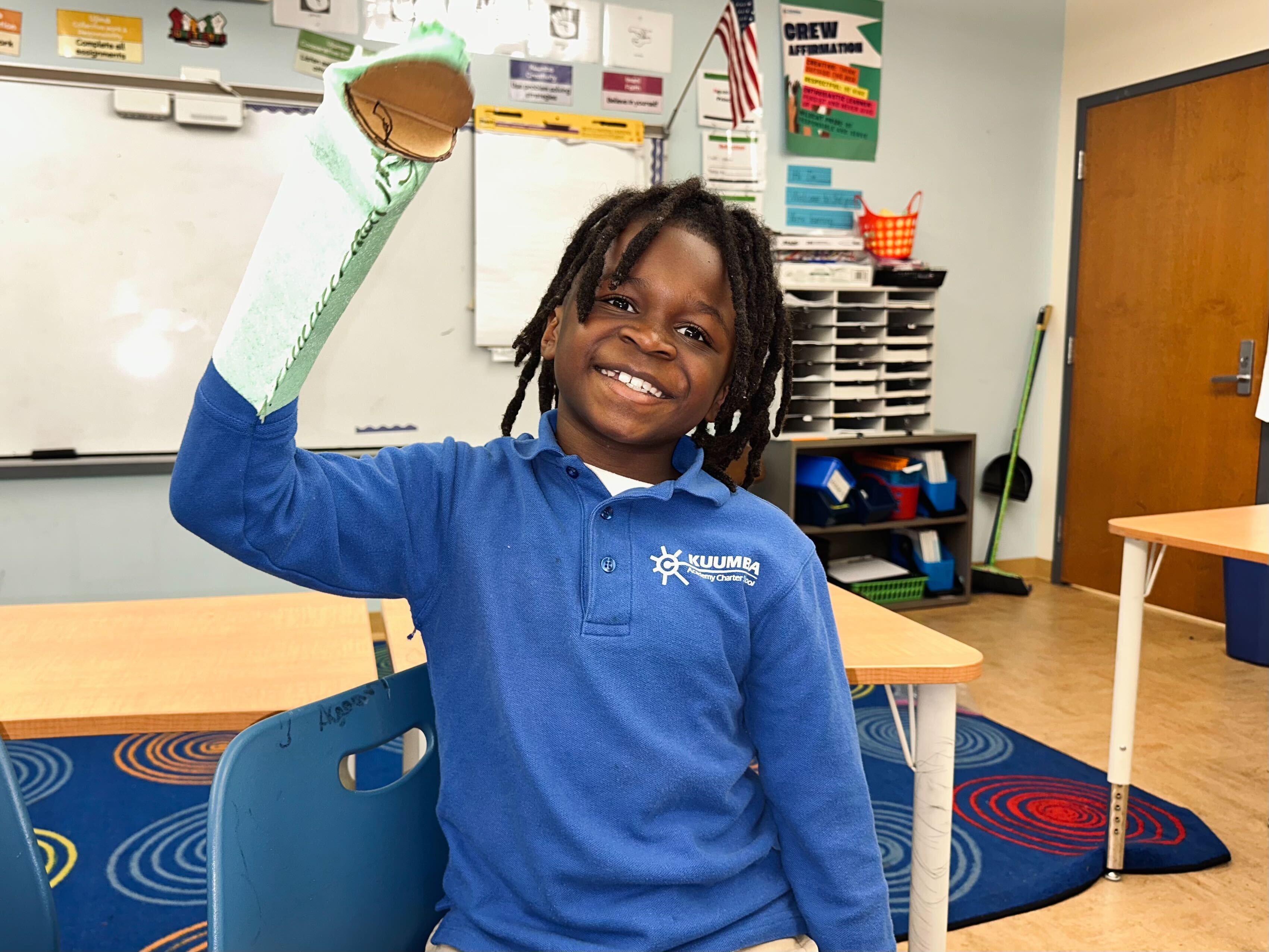

Students at Kuumba Academy use puppets to explore storytelling and self-expression in an effort to boost learning through arts integration.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

It’s the final stretch of the school year, but inside a third-grade classroom at Kuumba Academy Charter School, an arts-focused charter school in Wilmington, creativity is just beginning to bloom.

Sheets of colored paper cover desks as students, focused and engaged, cut, shape and imagine characters that will soon come to life. This puppet-making project is part of a three-day residency led by a professional teaching artist as arts and academics intersect in full harmony.

It’s more than an end-of-year craft. It’s part of a growing movement across Delaware that sees creativity not as a distraction, but as a powerful catalyst for deeper learning.

The puppets, crafted from felt and sewn by hand with needle and thread, are brought to life using bamboo barbecue skewers and cardboard for structure. Some students create otters or other animals. Others design human figures or scientists, each representing a unique message. Though the materials are simple, the outcomes are multifaceted as they blend art, science and self-expression.

“Kobe!” whispers a student as he launches his puppet into the air.

— Johnny Perez (@johnnyperez__) June 4, 2025

At Kuumba Academy in Wilmington, Del., 3rd grade teacher Emma Salisbury brings hands-on, engaging techniques into the classroom—using puppets to help students dive into ELA, story telling and self-expression. pic.twitter.com/uguAYTql0X

A statewide commitment to creativity

This collaboration reflects a growing educational approach known as arts integration. To an outsider, it may appear to be just fun and glue sticks, but to educators and policymakers, it’s a carefully designed framework that delivers measurable academic and emotional benefits.

“From the time that children enter our world, they have the opportunity to hear music, to see vibrant colors, to engage in movement and to play creatively,” said Lauren Conrad, an education associate for visual and performing arts at the Delaware Department of Education. “When they enter our schools, I think it’s imperative that we keep that creativity moving forward.”

Delaware has taken deliberate steps to embed arts into public education. Through state regulation, all students from kindergarten through sixth grade must receive instruction in visual and performing arts. And while not mandatory in higher grades, arts education must still be offered through grade 12 across public and charter schools.

“In Delaware, we’ve adopted the national standards for visual and performing arts,” Conrad said. “We are aligned to that, and that is a really important part of regulation and that we have them … When standards change, we demonstrate through coursework and assessment that our schools are aligning to those standards.”

Conrad also pointed to internal data supporting the long-term benefits of arts exposure.

“There is a correlation that you can see between students who are participating in arts courses and their SAT scores being higher than students who are not participating in arts courses,” she said. “So the more arts courses that students are enrolled in in high school, the higher their SAT score.”

This data aligns with national research. A study by UCLA professor James S. Catterall found strong links between consistent arts participation and academic achievement, particularly in music, math and theater.

“Students who report consistent high levels of involvement in instrumental music over the middle and high school years show significantly higher levels of mathematics proficiency by grade 12,” the study states. “Sustained student involvement in theatre arts … associates with a variety of developments for youth: gains in reading proficiency, gains in self concept and motivation, and higher levels of empathy and tolerance for others.”

Beyond academics, Conrad sees the arts as crucial to student well-being.

“Not from a clinical perspective, but personally I think that the arts have the ability to support students’ mental health and their growth across the board,” Conrad noted. “I think that there’s a lot of research done by professionals who have studied these types of relationships.”

One such study, conducted by Dakota Elston at California State University, Chico, reinforces the emotional impact of arts integration.

“Arts-integration provides a unique approach to teaching and learning that promotes positive social-emotional and academic growth and development. It creates a community and safe space for student learning to occur, which is key to benefiting all students in a holistic manner,” Elston notes in the study. “By engaging in play, children build on their existing knowledge, apply their skills and theories, and enhance language development, critical thinking, problem-solving abilities, and social skills.”

Art should be accessible

For Sheila Ross, program officer with the Delaware Division of the Arts, the arts aren’t just a subject. They’re a mirror of identity and belonging.

“Art is in us. Art is part of culture, which is in us,” Ross said. “We engage in the arts every day. We just don’t think about it. When you turn on your radio in the morning, that’s music. That’s art. It’s not separate from us. It’s a vital part of education.”

Ross plays a central role in supporting artist-in-residence programs across the state, working closely with the state’s Department of Education to ensure funding and curriculum align with educational standards. But beyond logistics, she sees her mission as fueling creativity.

“We’ve set up grants that mirror what people are asking for or looking for,” she said. “If [teachers] have an idea or a project they want to see come to fruition, they can come to us for funding support.”

One standout example is the IDEA Project, short for inclusion, diversity, equity and access. The project paired arts education with Black history initiatives under House Bill 198. In class, students explored historical narratives through theater and later got educational support from the Grand Opera House.

“It started with me calling a school and saying, ‘Hey, do you want to try this?’” Ross said. “They did, and we fully funded it. It’s an example of how the Department of Education, our organization and our arts organizations kind of made the project a success.”

The Delaware Division of the Arts offers a variety of grant programs and partnerships to help schools implement creative learning experiences. These include artist residency grants, funding for field trips, workshops and curriculum-aligned projects, as well as partnerships with institutions such as the Grand Opera House, Delaware Art Museum, Biggs Museum of American Art and Freeman Arts Pavilion.

The Kuumba example

That kind of collaboration is the foundation of the Delaware Institute for the Arts in Education, which works with schools in all three counties to build customized arts programs led by professional artists. Executive Director A.T. Moffett described it as a way to expand access to arts education, particularly for students who may not have it otherwise.

“Our niche within [the program] is that we go into the schools during the school day,” she said. “It’s an important component because when you go into schools during the school day, you have reached the widest cross section of students. Not all students have access to after-school programming, access to studios and artistic offerings that happen in the evening.”

“It allows the students who do experience the program to see it as interwoven and as intrinsic to their learning rather than an extra,” Moffett added.

By embedding artists directly into classrooms, the institute ensures that the arts are part of the fabric of learning and not just an add-on. Whether it’s a puppet-making residency, a live performance or a cross-disciplinary lesson, each experience is codesigned with educators to meet curriculum goals.

That kind of intentional integration came to life in Emma Salisbury’s third-grade classroom at Kuumba Academy, where she serves as team lead. Salisbury, now in her fourth year at Kuumba, immediately saw a way to tailor the program to her students’ strengths.

“I’ve noticed really early on this year that my current group of students are very into visual art and drawing and sort of creating things,” Salisbury said. “So, this puppet project is just sort of the perfect connector to all of that.”

This spring, her students created puppets tied to their English-language arts unit on global water issues.

“The current unit for ELA is to read about problems related to water around the world. They learned about problems with people not having enough water, problems with people not being able to get to water and having to walk really far, and then also water pollution,” she said. “And we focus mainly on water pollution … because in Wilmington, pollution, like on the streets, is a problem and it is something that the students can relate to.”

The curriculum encouraged students to create a video public service announcement — but Salisbury saw an opportunity to take it further.

“We decided that the video itself is already sort of adding a little artistic element, but creating the puppet as well will add sort of another aspect to it,” she said. “We sort of brainstormed all these different questions that we might ask a scientist or someone who lives by water, or even if we could talk to an animal that lives in the water, what could we ask them about water pollution and its effects?”

Through this approach, students brought to life characters ranging from scientists to river otters affected by pollution. As they brainstormed, designed and sewed their puppets, they merged science, language and art into one unified project.

The impact was especially noticeable with students who arrived midyear.

“Even like this year, I had two students come sort of in the middle of fall … There’s one in particular, she really blossomed into being very artistic,” Salisbury said. “She’s made a ton of growth in reading this year, and writing as well, which is super exciting. And I remember right before winter break she even said to me … ‘Thank you so much for all that you’ve taught me. Like, my old school… I didn’t learn like this. I didn’t understand anything.’”

Salisbury believes immersing into the arts gives students more control over their learning — especially during a season that can be overwhelming.

“Opening myself up to adding arts in … helps to make things seem a little less serious and … adds a little more fun and joy into what we’re doing,” she added.

A teaching artist’s perspective

Teaching artist Kate Testa, who led the residency, said the puppet-making project is more than a classroom exercise. It’s a chance to grow confidence through creativity.

“The puppet can be whatever it wants to be,” Testa said. “The children, they design their own … it’s a creature that lives in water or a water advocate.”

Testa emphasized that the work also builds fine motor skills and strengthens focus.

“I’m always trying to develop fine motor skills and things like that,” she said. “The lessons that I wanted to impart are like getting kids to work on their cutting, work on sewing, that fine motor skill that we don’t get as much … sewing is like a zen practice sometimes.”

But beyond technique, the experience builds emotional and social learning.

“You see them interacting with each other differently,” she said, adding that when students finish making the puppet, “they’re having these conversations with each other. There’s creativity. They’re making up these stories. They’re talking as the characters that they develop.”

For some students, the puppet becomes a new voice.

“The puppet ends up being kind of an extension of the person. So if they’re a little bit shy, maybe the puppet can be a little bit more active. There’s a way for them to express themselves or be creative. Even just the acting or the movement of the puppet,” she said.

Testa hopes for all her students to walk out of the room with more confidence.

“I want them to think, ‘I have the ability to do something that I maybe didn’t think I could.’ Because a lot of them are a little overwhelmed in the beginning and then by the end they’re building that confidence in themselves,” she said. “Art making is about instilling those skills of self-reliance, creativity, confidence.”

The stitch that ties it all together

At the end of the residency, it’s not just the puppets that students take home. It’s pride, a sense of curiosity and the satisfaction of learning through something they made with their own hands.

“They’re always so excited to bring them home and show them to their brothers and sisters,” Testa said. “And I hope that storytelling and that narrative … transitions and carries outside of the classroom.”

For educators, the path to arts integration doesn’t have to be walked alone. With statewide programs and support from organizations like the Delaware Institute for the Arts and the Delaware Division of the Arts, teachers have access to materials, training and creative partnerships to bring this kind of learning to life in their own classrooms.

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series that explores the impact of creativity on student learning and success. WHYY and this series are supported by the Marrazzo Family Foundation, a foundation focused on fostering creativity in Philadelphia youth, which is led by Ellie and Jeffrey Marrazzo. WHYY News produces independent, fact-based news content for audiences in Greater Philadelphia, Delaware and South Jersey.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.