Delaware marks 70th anniversary of its role in landmark Brown v. Board decision

The First State still struggles with creating a quality education for all students despite its consequential role in the Brown v. Board decision.

Listen 4:42

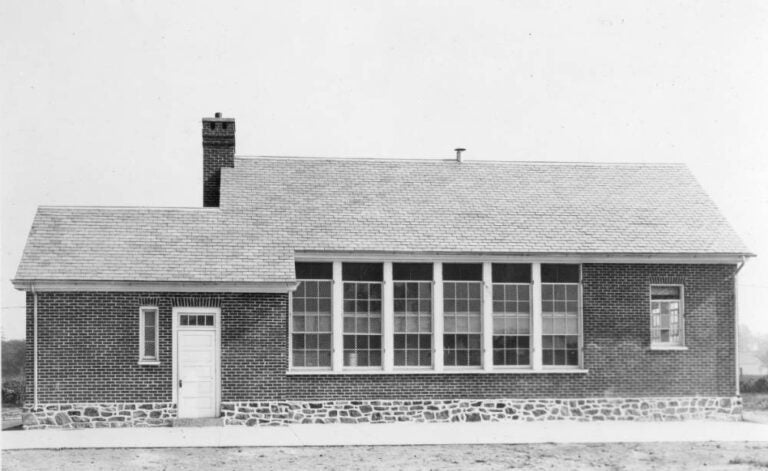

A rear view of Hockessin Colored School #107C (Courtesy of Hagley Library and Museum)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

This story was supported by a statehouse coverage grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

This month marks 70 years since the United States Supreme Court overturned the principle of separate but equal in America’s schools.

But Delaware’s vital role in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education landmark court ruling is often overlooked. Seven decades later, some say the promise of racially desegregated schools and equality in education remains elusive.

The U.S. Supreme Court originally established the separate but equal doctrine nearly 60 years earlier, legalizing racial segregation in all public areas, including schools, in 1896.

James Knott, who goes by Sonny, attended the Hockessin Colored School #107C between 1937 and 1944. He said during segregation, separate was not equal.

“We couldn’t go to the restaurants, couldn’t go to the movies, none of that,” he said. “They had one movie in the city for colored people, and that was at Eighth and French, called ‘The National.’”

The 1954 Brown v. Board Supreme Court appeal was made up of four other cases besides Delaware, including Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia and Washington, D.C.

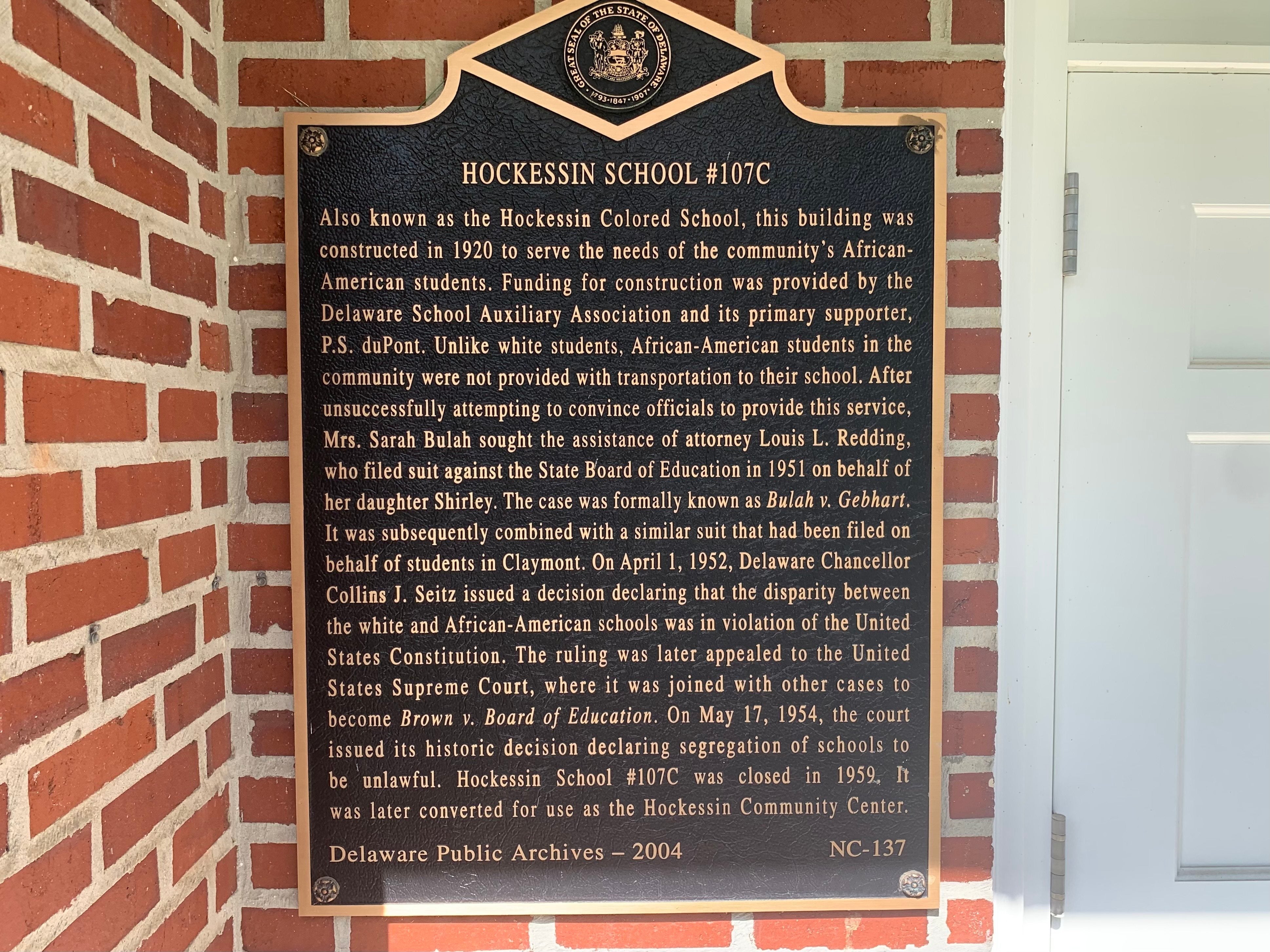

Louis Redding — Delaware’s first Black attorney and a lawyer for the NAACP legal defense — argued the two Delaware school segregation lawsuits. In one case, Gebhart v. Belton, eight students were denied entry to Claymont High School while being bused in Wilmington for school. In the second case, third-grader Shirley Bulah was denied the right to ride on a bus that passed by her house everyday with white children to the Hockessin school or attend a white school.

The challenges by Redding and others across the country were part of a coordinated effort by the NAACP to prove segregation was unconstitutional. Black families asked the states to allow their children to attend white schools — only to be told no.

Redding’s arguments were the only ones of all the cases that were successful. Rev. J.B. Redding said her father felt very isolated as an attorney fighting injustice.

“When he first began practicing before the courts, they tried to keep him in the back of the courtroom in the segregated section for Blacks,” she said. “That’s the courage in him — he just refused and came up front.”

Chancery Court Chancellor Collins Seitz heard the combined First State case in 1951. Unlike the four other cases in the Brown decision, Delaware was the only place in the country where the courts ruled in favor of the Black families.

Local historian Lanette Edwards said Seitz is an unsung hero in the landmark Brown ruling.

“If we don’t do anything else, we need to champion that man. Because without him, you don’t have integration in the United States of America,” she said.

Seitz visited the Black and white schools and concluded they were not equal. Seitz’s son, Collins Seitz, Jr., is now a Delaware Supreme Court justice. He said what his father did was unique from what other judges did in the Brown cases.

“He ordered the immediate integration of the Delaware schools,” he said. “Most states said, ‘I will give you time to bring the Black schools up to the level of the white schools.’ My father said, ‘No, justice delayed is justice denied.’”

After the Delaware Supreme Court sided with Seitz, the state appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, becoming part of the Brown case. In 1954, the court ruled separate but equal was unconstitutional, using many of the arguments and language from the First State’s case.

Delawareans still debate how successful school desegregation has been in the state.

Sonny Knox said those court rulings improved opportunities for Black residents.

“That was the beginning of it, so to speak,” he said. “Then opportunity opened up, jobs opened up and when jobs opened up, you started getting better jobs and better salaries. Now you can get better other things. So, it opened a lot of doors.”

Hockessin Colored School #107C closed in 1959. Busing students to other schools in New Castle County in the mid-1970s became very controversial, drawing heated protests.

Gary Hutt with the Howard High School Alumni Association said there’s still a desire by some today to maintain racial separation in schools.

“There’s still a lot of parents out there that fight, look for other ways to keep their kids from having to be around kids unlike their own kids,” he said. “That’s unfortunate.”

Some said the lack of a quality education for disadvantaged students in the state shows there’s still work to do on desegregation.

But others say it might be more beneficial for groups to have their own schools.

Elizabeth Lester was part of the first wave of students to go to desegregated schools in Delaware in the early 1960s. She attended Hockessin Elementary School as a first-grader. She said she went to public schools until her first year of high school, when she left because of bad previous experiences with school staff.

“I really think that we would have been better off if we had the books, the learning to be in Black schools seriously,” she said. “Because you learn more.”

In 2020, Delaware settled a lawsuit that accused the state of being complicit in the disparities experienced by students. An independent report released last year recommended adding up to $1 million to help students who are low-income, disabled or English-language learners.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.