The Curtis Institute has been Philly’s musical bedrock for 100 years

The Curtis marks its 100th birthday this weekend with concerts and an open house of its historic Rittenhouse Square campus.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

In the run-up to its centenary season, the Curtis Institute of Music recently conducted audience surveys to see what people thought about the institute.

“One thing that came back that was very interesting, is that Curtis has cornered the market on being Curtis,” said president and CEO Roberto Díaz. “Nobody does Curtis better than Curtis.”

The Curtis will show off what it means to be “Curtis” this weekend to mark its 100th birthday Sunday with three days of concerts and an open house of its historic Rittenhouse Square campus. On Saturday, the school’s New Music Ensemble will perform a concert of works by Gabriela Ortiz, one of Mexico’s premiere contemporary composers who’s currently in residence at both Curtis and Carnegie Hall in New York City.

This weekend, the Curtis is also releasing an album of newly recorded music by nine composers who have gone through Curtis, including Samuel Barber (’34), Leonard Bernstein (’41), Julius Eastman (’63), Jennifer Higdon (’88) and David Serkin Ludwig (’01).

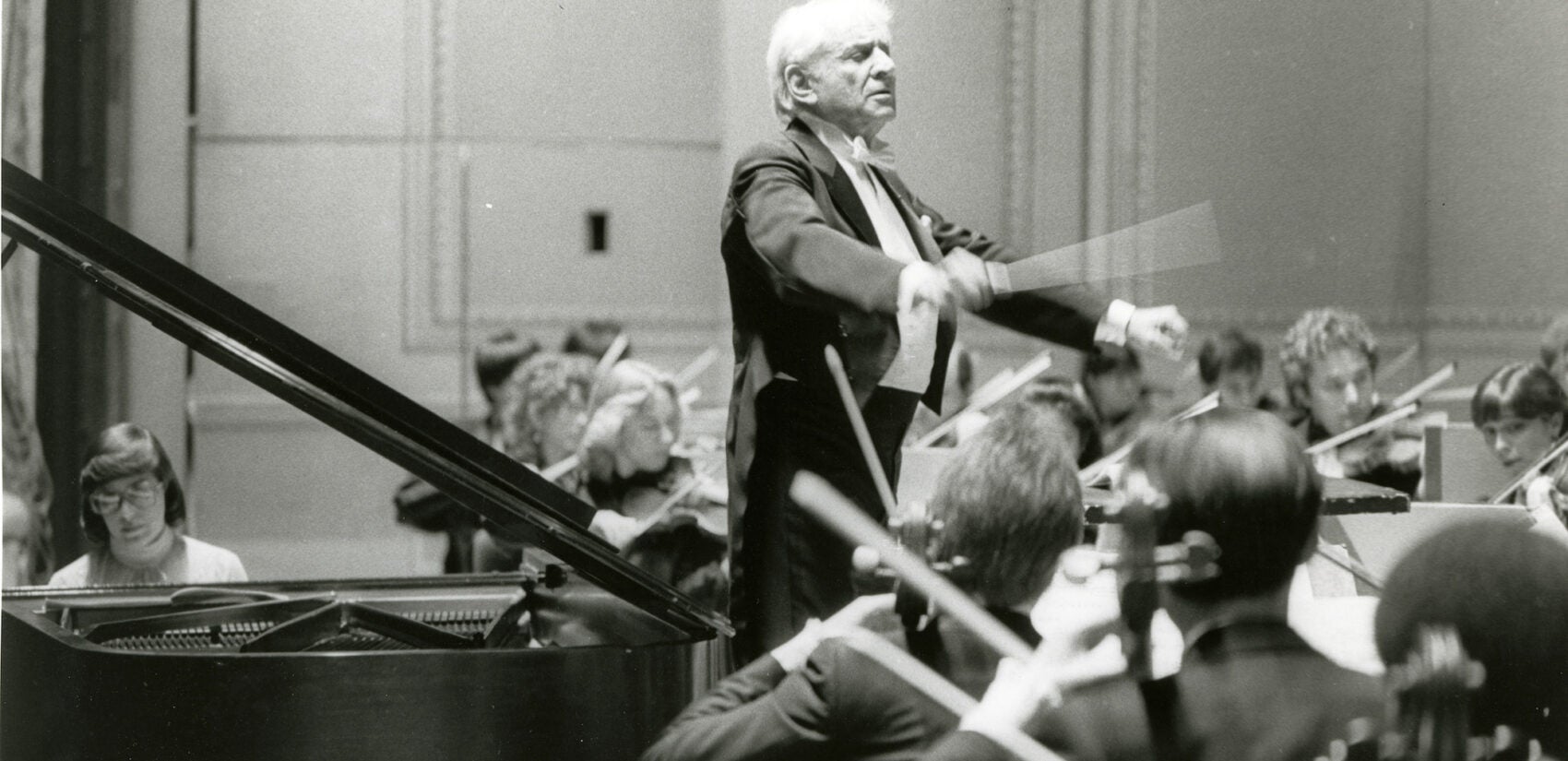

On Oct. 13, 1924, the Curtis Institute of Music began fully formed. Founder Mary Louis Curtis Bok was heir to the Saturday Evening Post and Ladies Home Journal magazine fortune. Her money and contacts in the musical world — including Philadelphia Orchestra conductor Leopold Stokowski and Josef Hofmann, one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century — allowed Curtis to launch at a world-class level from day one.

“Tapping into the world of these two incredibly high-visibility artists of the time, they were able to get people to come and join the faculty of this amazing school,” Díaz said. “The school has always had the core belief that the best faculty brings the best students, and the best students get you the best faculty. It’s just a cycle.”

For a century, Curtis has maintained that reputation. The school is one of the most selective of any college or university, on par with Harvard, with a student-to-teacher ratio approaching 1:1. There are 115 faculty members for 165 students.

For 100 years, the tuition has been $0. Everyone selected to study at Curtis gets a full scholarship, one of very few schools in the world to do so.

“Merit scholarship is part of the special sauce,” Diaz said. “If you belong here, you can be here. It’s really as simple as that. The tuition-free policy is what for many years made the school unique.”

Students who graduate from Curtis often move on to positions in major orchestras, including the Philadelphia Orchestra. When Diaz, himself a Curtis graduate, was principal viola with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 2005, more than 60% of its musicians came out of Curtis.

“The Philadelphia Orchestra and the Curtis Institute of Music have a deep and close and long relationship for — well, since Curtis was founded 100 years ago,” said the orchestra’s president and CEO Matias Tarnopolsky. “It is one of those legendary conservatory-orchestra relationships.”

From his office in the Kimmel Center on Spruce Street, Tarnopolsky has a front-row view of that relationship, as musicians carrying instrument cases walk back and forth between the Kimmel and the Curtis four blocks away.

“Ricardo Muti is about to come to the Philadelphia Orchestra at the end of the month,” he said about the former Philadelphia Orchestra music director. “He said, ‘Make sure that students in the area know that they can come and hear my rehearsals.’ Philadelphia is a musical town, and Curtis and the Philadelphia Orchestra are anchors of that tradition.”

The Curtis student body comes from around the world, sometimes as young as 13 or approaching their 30s. Because of the rigorous selection process, all students arrive with an already high level of proficiency, which further elevates everyone.

“Curtis has been an incredible place to collaborate with really talented musicians and to write for orchestra,” said composition student Leigha Amick in the WHYY-TV program “On Stage at Curtis.” “It’s a very rare and special thing for a young composer to get this many chances to write for orchestra.”

One of the hallmarks of Curtis is the support students get from one another. Curtis regularly hosts afternoon tea in the lobby of its original building on Rittenhouse Square to encourage students to emerge briefly from endless practicing and socialize.

“We all interact with each other in rehearsal, in the cafeteria we’re all eating together and socializing,” said percussionist Griffin Harrison. “You would never know that we come from, like, a million countries.”

Mezzo-soprano singer Katie Trigg came to Curtis from Ngāhinapōuri, a rural town in New Zealand’s North Island with a population of 300 people.

“Curtis for me represents a huge step forward from where I’ve come from,” she told “On Stage at Curtis.” “New Zealand is a really great environment for nurturing young singers. We have a lot of amazing singers coming out of there, but there has to be a jumping point. For me, Curtis is that jumping point.”

The Curtis has a historic reputation for training students for careers in the world of classical music, i.e. orchestras. But, as the classical music world evolves, a chair in one of the Big Five orchestras may no longer be the ultimate goal for students.

“We really believe that our responsibility is not to dictate what a career looks like, but train these young incredibly talented musicians to have as varied and diverse career paths as they can imagine,” said Díaz.

For example, he points to “Time for Three,” a contemporary trio that will be performing later this month at the Kimmel Center as part of the Curtis’ centenary season. “Time for Three” is a Grammy-winning trio, a self-described “classical garage band” known for making bluegrass, hip hop and pop arrangements for an otherwise classical string ensemble.

Two members of “Time for Three” are Curtis graduates: bassist Ranaan Meyer and violinist Nick Kendall, who attended alongside his sister, Yumi Kendall. The two took divergent paths: While Nick is bending musical genres in his trio, Yumi is assistant principal cellist with the Philadelphia Orchestra and is on the faculty of Curtis.

Yumi also started a podcast in 2023 with fellow Curtis graduate and Orchestra member Joseph Conyers, “Tacet No More,” talking about concerns within the classical music industry, particularly issues around diversity and equity.

The podcast fits with a relatively new aspect of Curtis’ curriculum: social entrepreneurship, or training students to get involved in the civic life of the communities they work in.

“That’s really developing the awareness of the role of the artist in their community,” Díaz said. “Do we have a responsibility to the community that we inhabit? If the answer is yes, which it is, then how does that manifest itself?”

After Conyers left Curtis in 2004, he moved to Atlanta where he started Project 440, supporting young people in underserved schools to develop musical skills and discover otherwise unseen opportunities. He has since moved back to Philadelphia, became the first Black principal bass player at the Philadelphia Orchestra, and brought Project 440 with him.

Another Curtis student, Jessica Chang, started a youth music program in 2012 during her final year of studies with support from Curtis. Chang then moved to San Francisco, where she continues to direct the program as Chamber Music by the Bay.

In 2022, the Curtis Institute established the Young Alumni Fund, which financially supports its graduates’ social entrepreneurship projects, with grants up to $10,000.

“The school has been successful as it has been, and has had the impact that it has had because its mission has been fairly narrow,” Díaz said. “We do what we do, and we try to do it in the best possible way. When we evolve it’s about doing what we do in better ways as opposed to the temptation of adding more things.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.