CIA photos from U-2 spy planes of the 1950s have new life in archeology at Penn Museum

The Penn Museum is showing declassified images from 13 miles in the air, giving archeologists new tools to study ancient cities.

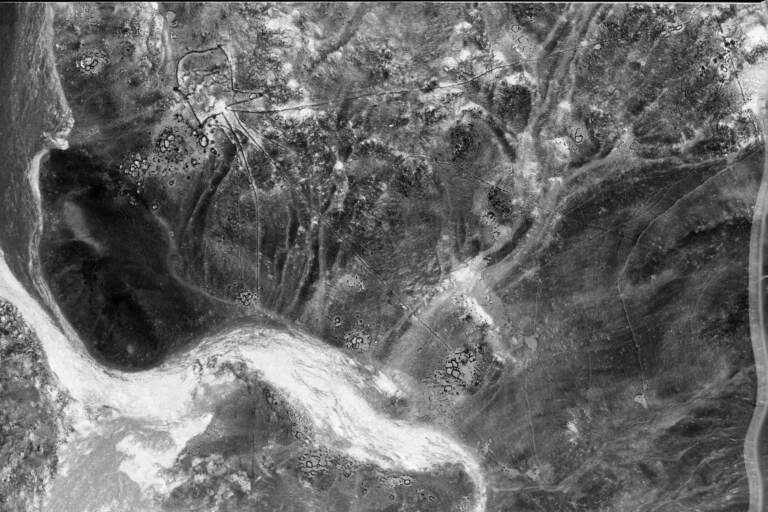

U-2 spy plane images capture the thin stone walls of prehistoric hunting traps, called "desert kites," located in the black basalt desert (Harra) of eastern Jordan. Thousands of years ago it was a land of plenty for hunters and herders. (Provided by Emily Hammer)

Twenty-five years ago, top-secret aerial photography taken by U-2 spy planes were made available to the public, having been declassified in 1995 by President Bill Clinton.

Although publicly available, those images are not really accessible.

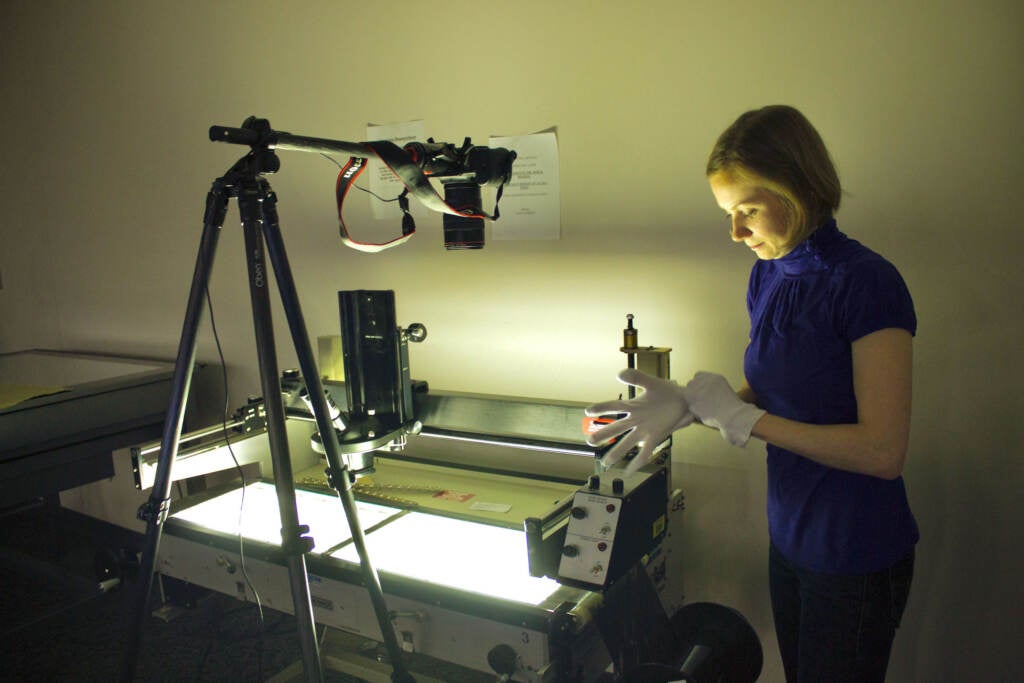

The miles of film rolls were never digitized, or even printed. To view them, researchers must request them by the roll and travel to the National Archives in Washington D.C. to view them. Each reel contains over 200 feet of film, with about 133 images that are 9×24 inches large.

No finding aides were ever created, meaning hundreds of thousands of images have no description of what they show.

“In order to access them, you have to piece together how they are organized,” said Dr. Emily Hammer, a landscape archeologist at the University of Pennsylvania.

She and colleague Jason Ur of Harvard University have spent years puzzling together U-2 spy plane images to see traces of the ancient world. Some of what they have found is now on view at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology’s exhibition “U-2 Spy Planes and Aerial Archeology.”

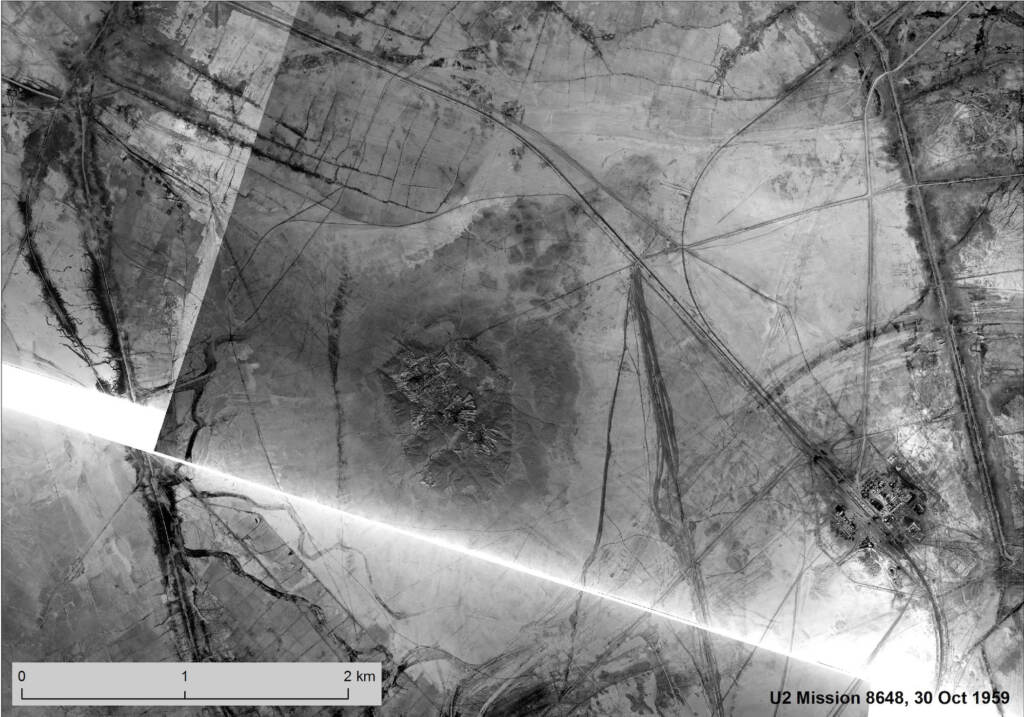

The Lockheed U-2 spy plane is a high-altitude military reconnaissance jet able to take high-resolution photos of the earth from 70,000 feet in the air, about twice the altitude of typical commercial airliners.

Still used to this day, its heyday was during the Cold War of the 1950s and 60s when the CIA used the jets to criss-cross the globe in search of military intelligence, methodically taking pictures of everything and anything in its flight path.

A mission could last 12 hours, taking pictures every seven seconds. Hammer focused her research on 11 known flights over the region of the Middle East, which, by her calculation, produced more than 54,000 frames on 13 miles of film footage.

“There are some declassified CIA documents that list the planned coordinates for the mission, but they don’t closely correspond with where the pilots actually flew,” she said. “You have to look through the film and eventually you might recognize something, then piece back from that.”

These images do not offer a bird’s-eye-view, rather at 70,000 feet high they are akin to a god’s-eye-view. Patterns come into view showing leftovers from built environments. Subtle gradient differences in the earth can suggest the shapes of ancient cities that have long since disappeared.

Hammer likens archeological landscapes to staring at the brushwork of an impressionist painting.

“If you stand very close, you only see the little dots of paint that are different colors. You don’t understand their relationship to a broader pattern. They don’t necessarily make sense,” she said. “But when you pull back, you can see, ‘Oh, there’s a riverbank and a woman with a parasol, or a church,’ or whatever is in that impressionistic painting.”

If you could stand back 70,000 feet, or roughly 13 miles away, the ancient world comes into view.

The large-scale prints of the U-2 images at the Penn Museum show enormous hunting traps dating back about 9,000 years. People in what is now southern Jordan would draw lines in the earth traveling thousands of feet, sometimes with low walls or even just flat stones embedded in the ground. Animals would instinctively follow those lines leading into pens acres wide, becoming trapped and killed for food.

Called hunting kites, because of their shapes with long tails, the aerial images show how they were constructed, and the ingenious ways the ancient people linked their landscape traps together into networks spanning almost a mile, without the benefit of a blueprint.

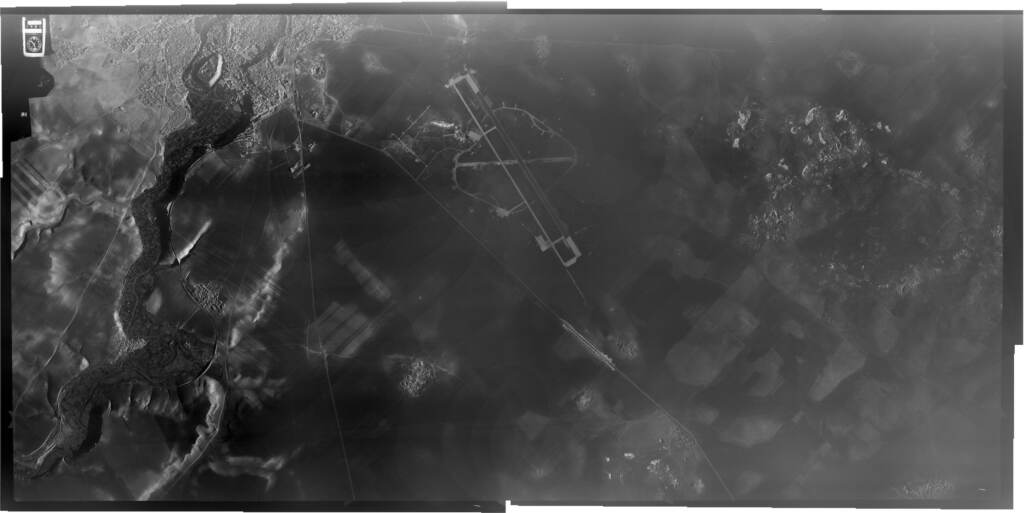

The spy planes flew over the ancient city of Ur in Mesopotamia, one of the first cities in the world. Ur has been excavated for almost 170 years, but these images show what was likely its outer suburbs.

“We know a lot about the central part of the city where the elite people were living, where the temples and palaces were,” said Hammer. “But we don’t know so much about these suburbs where probably less elite people were living, where there was a lot of industry and crop production.”

The U-2 aerial photo archive is not the only one available to archeologists, but it’s probably the most difficult collection to work with. Newer imagery from orbiting satellites and recent military surveillance is more easily accessible. Archeologists take their own images from cheaply available drones.

But the U-2 footage offers something no other collection has: incredibly high-resolution pictures of large swaths of landscape from the 1950s and 60s, sixteen times clearer than satellite imagery of that time.

That mid-century time frame is critical. Hammer can see the landscape before development, agriculture, and climate change altered the ground.

Case in point is the marshland of southern Iraq, which in the 1950s had a thriving population of about half a million people who made housing out of bundled reeds, called phragmites, and largely fished for food.

“We think of Iraq as a desert country, and it is for a large part, but the southern part of Iraq, with the flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, used to be a massive seasonal wetland that people lived in for thousands of years,” said Hammer. “This is a way of life that doesn’t exist today.”

Modern dams restricted the flow of water into the marshlands. In the 1990s, Iraq leader Saddam Hussain deliberately drained the water from the marshlands to drive rebels to his rule out of hiding.

After the overthrow of Hussain in 2003 locals broke some of the dams, restoring the land to marshes. In 2016 the area was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

While people are beginning to return to the marshes, the population is not what it was 70 years ago when the U-2 planes captured images of life in the 1950s.

“In these photos, they’re detailed enough that you see individual people’s houses and the animal enclosures that are associated with them,” said Hammer. “And the little agricultural fields and the narrow boat paths that they were using to travel to surrounding villages.”

These case stories of what the U-2 images make visible are explained in the Penn Museum show, which also encourages you to be a spy, yourself, or the younger person with you. Some of the wall text can only be read through a “decoder” key (a red cellophane viewer) available at the front.

A mock-up of a U-2 cockpit was built into the museum exhibition, with jet flight sound effects. Visitors can sit in the pilot’s seat and get a sense of what it felt like to be in the air.

The U-2 is known as one of the most difficult planes to fly: the cramped cockpit and restricted vision through the windshield made it almost impossible to land. Pilots were often guided to the runway by a car racing ahead on the ground to show them a route to follow.

“It was incredibly dangerous to fly these planes,” said Hammer “They had to be very light to fly extremely high, so they didn’t have normal sorts of safety features.”

When Hammer was slowly piecing together flight paths to identify the terrain in the photos, she spent a lot of time looking at what the pilots would have seen during their long flights, in particular Gary Francis Powers, who was shot down in Soviet airspace in 1960.

It was Power’s espionage trial that exposed the secret U-2 project. He was convicted as a spy and imprisoned in the Soviet Union, returning to the U.S. two years later in a prisoner exchange. His story is briefly told in the exhibition.

Now that Hammer has done the diligent work of identifying locations, she finds herself more able to focus on the images themselves.

“I think, honestly, much more about the beauty and discovery of the photographs,” she said. “A lot of the things that you see in these photographs are really beautiful.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.