Charlie Secrest, 82, Southern ‘tomcat’ in Delaware, fixer of cars and father who ‘made it clear he cared’

Charlie Secrest’s family remembers a complicated man: stubborn, yet a patient teacher. Rough around the edges, yet loving — in his own way.

Listen 3:03

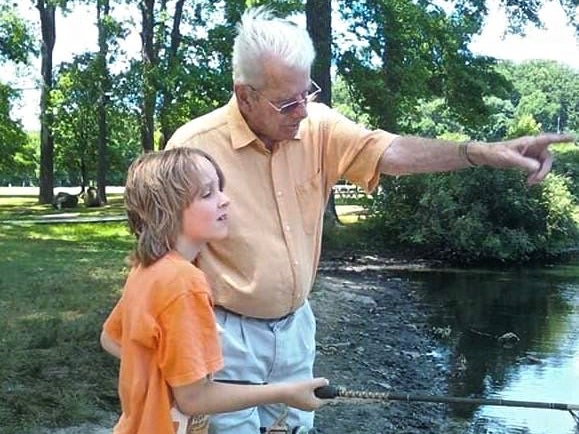

Charlie Secrest teaches his grandson, Connor, to fish at Bellevue State Park. (Provided by Terri Hansen)

This story is part of WHYY’s series “COVID-19: Remembering lives we’ve lost” about the everyday people the Philadelphia region has lost to the coronavirus pandemic, the lives they lived, and what they meant to their families, friends and communities.

A combination of Dean Martin, Andy Griffith and James Garner. That’s how Terri Hansen describes her father, Charlie Secrest.

“He was a complete tomcat, good looker, good southern boy — and he’d kick your a** if he needed to,” she said with a laugh.

The 82-year-old died in a Wilmington nursing home April 6 after testing positive for COVID-19.

Molded by his own difficult upbringing, Secrest had his flaws; he was stubborn, kept up a hard shell around him at times and had complicated relationships with his family, his daughter said.

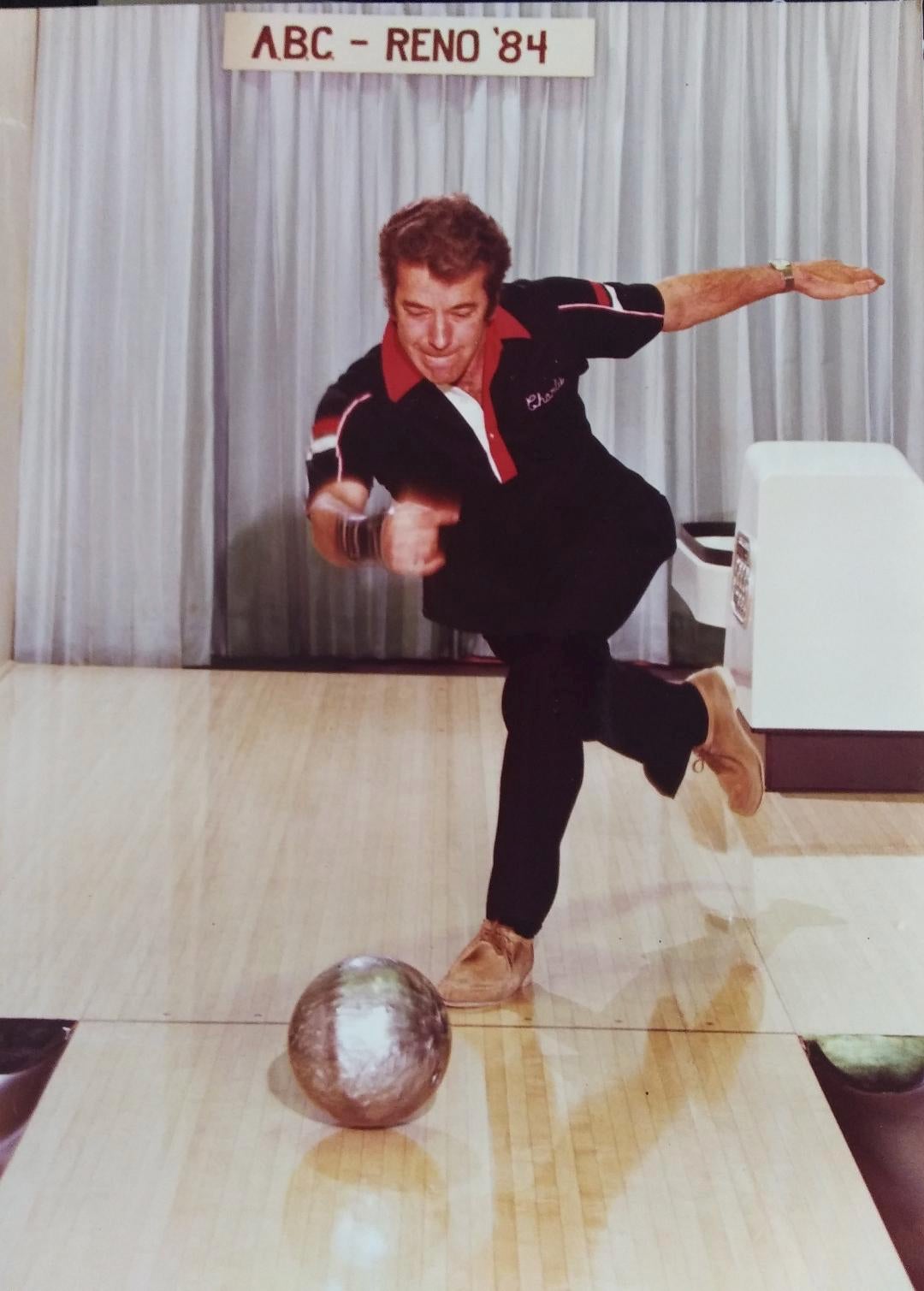

But Secrest was also known for his lightheartedness and spontaneity, and his stubbornness gave way to the utmost patience when he played the role of teacher, whether it was bowling or fixing cars. After his death, former bowling students reached out to Hansen to tell her about the impact Secrest had on them as kids.

He showed his love in his own way, his daughter said.

“He did the best he could, and when the best wasn’t awesome, it was still the best he could do,” Hansen said. “So often we judge our elders and don’t see what it comes from, and the more I learned about my dad, the more I understood my dad, and the more I could love him the way he was.”

Graduate of ‘Roads High School’

Secrest was born in 1937 in Mount Airy, North Carolina, where Andy Griffith was born. The city is believed to be the inspiration for Mayberry, the setting in “The Andy Griffith Show.”

Secrest lived in the town, which sits at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, until he was about 11 years old. He grew up living in poverty, working on his grandparents’ small tobacco farm, and often had to fend for himself as a young boy.

While Secrest had a tough childhood, his daughter said he also recalled warm memories of his artistic father, a self-taught musician who taught him how to play the guitar. Young Charlie sometimes played music with his father on the porch at night, sipping moonshine when he could get away with it.

When Secrest was about 11 years old, he left North Carolina with his mother and her new husband, frequently moving to new states — and the instability of moving was challenging for him, Hansen said. But when Secrest was in his late teens, his stepdad settled the family in Delaware for a job opportunity after returning from the Korean War.

Secrest never graduated from high school. But a resume he wrote in the 1960s to try to get a job at a trucking company said he graduated from “Roads High School” — the school of the road.

Secrest worked hard to achieve success without a diploma. He had an 18-wheeler truck he named Tinkerbell, which he used to help him land odd jobs, calling businesses he found in the yellow pages to offer work.

“’I’m picking up a load of apples in Front Royal, Virginia. Do you have a load that needs to go there?’ And he’d take that load to Front Royal, unload it, then pick up the apples and take them to Jersey,” Hansen said.

Secrest, a self-taught auto mechanic, eventually became certified and worked for several car dealerships, until he opened his own mechanic shop. Working on cars not only was a business, but a passion, his daughter said. He was involved in the Delaware Street Rod Association, transforming beat-up classic cars made before 1949 to travel on modern roads.

Hansen has fond childhood memories of her father. When she was 12, her father participated in her Girl Scouts roller-skating trip.

“He volunteered to be our chaperone, and put on roller skates and roller skated with a bunch of 12-year-old girls,” she said. “He was the only father that came. It was all the moms — and my dad. And I thought I was the coolest Girl Scout there, like ‘I got my dad.’”

Secrest always had a warm temperament with children, said Peggy Thomas, who grew up next door to Hansen and her family. When Thomas took up bowling as a middle schooler, Secrest coached her at Silverside Lanes, then on Concord Pike in Wilmington, where he was in a competitive bowling league.

Secrest was patient, Thomas said. When she made technical mistakes during competitions, Secrest told her in a soft, calm voice how to improve her game in the next round.

“I still love bowling and I still carry those skills with me today,” Thomas said. “Whenever I’m bowling, I always think of Charlie. If it weren’t for him, I probably wouldn’t be very good at it.”

In his later years, Secrest enjoyed teaching his son-in-law Drew Hansen how to fix cars. While Hansen said Secrest could sometimes be very stubborn and opinionated about other aspects of life, when it came to teaching, patience was his virtue. When he aged and was no longer able to do the physical work on cars, he talked his son-in-law through the process.

“For whatever reason, I think because I’m left-handed, I’m always forever mixing up left and right,” Drew Hansen said. “And when you’re working on a car it can be challenging sometimes to get the direction straight when you have to loosen or tighten a nut, because depending on how the nut is facing relative to where you are, it might change the direction you need to turn it.

“Any time I’d mess this up, I’d hear him mumbling over my shoulder, ‘Lefty loosey, righty tighty,’ to remind me which way to turn things. I heard that in my ear more times than I can count, and I still hear it every time I mess up.”

Since those days, Hansen has repaired a radiator, and replaced sensors and gaskets on his own. Those previous lessons gave Hansen the confidence to problem-solve and find a solution.

‘He made it clear he cared’

Secrest also doted on his grandson Connor Hansen, 15, introducing him to music and buying him a ukulele and bass guitar. But the teen’s most vivid memory of his granddad is the first time he taught him how to fish when he was 7 or 8.

“I don’t think he ever directly said, ‘Connor, I love you,’ or anything like that. But I knew he cared. He made it clear he cared,” Connor said.

During his life, Secrest married and separated from two wives. He had seven children during his first marriage, and two children with Hansen’s mother. Hansen said her dad was a “lady’s man and unrepentant flirt” through much of his life — but at the time of his death, Secrest had spent 40 years with his girlfriend, Violet Kirkner.

Secrest continued to care for Kirkner after she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

“The sun rose and set on Violet completely,” Hansen said. “She was his everything. He cooked for her, cleaned for her, did her laundry — after the Alzheimer’s set in he made sure she had her gold earrings in every day, her nails were painted, her makeup was on, her hair was done.”

But while he was in the hospital for a bad fall last year, Kirkner moved into Brandywine Nursing & Rehabilitation Center in Wilmington. When it became clear Secrest could no longer live independently, he left their home in Claymont and moved into the same nursing home as Kirkner. Shortly after, he was diagnosed with Lewy Body Dementia, but Hansen said until he got coronavirus in April, he did well considering his dementia.

Kirkner died on Friday, and this week, it was confirmed she also had COVID-19.

Hansen said her relationship with her father was rocky sometimes, especially after her parents separated. But while they were sometimes distant, the pair became very close over the past dozen years.

Secrest had a tough outer shell Hansen suspects he developed in childhood — he didn’t even wince or take pain relievers when he hit his head and had to get stitches. He didn’t show affection through words or hugs, but through his actions.

About 10 years ago, Hansen developed hyperthyroidism and needed to undergo surgery to have half her thyroid removed — she was terrified. Her dad didn’t provide words of affirmation, but comforted in his own way.

“The day before the surgery, my dad shows up at my door and he’s got pinto beans, cornbread and diced raw onion — and that was like childhood comfort food,” she said.

“He crumbled the cornbread that was cooked in an iron skillet, and then you put the pinto beans in some pot liquor on top and sprinkle it with raw onions, and then you try to slow down to taste it while you shovel it in your mouth. And that was his way of saying, ‘I’m thinking about you, and caring about you and I want you to be okay.’”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)