Can gentrifiers be good neighbors?

A recent college graduate who moved to West Philadelphia this year reflects on how to be a good neighbor when you are part of the force that is changing a neighborhood.

A view of the Philadelphia skyline from the 52nd Street station on the Market-Frankford elevated line in West Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

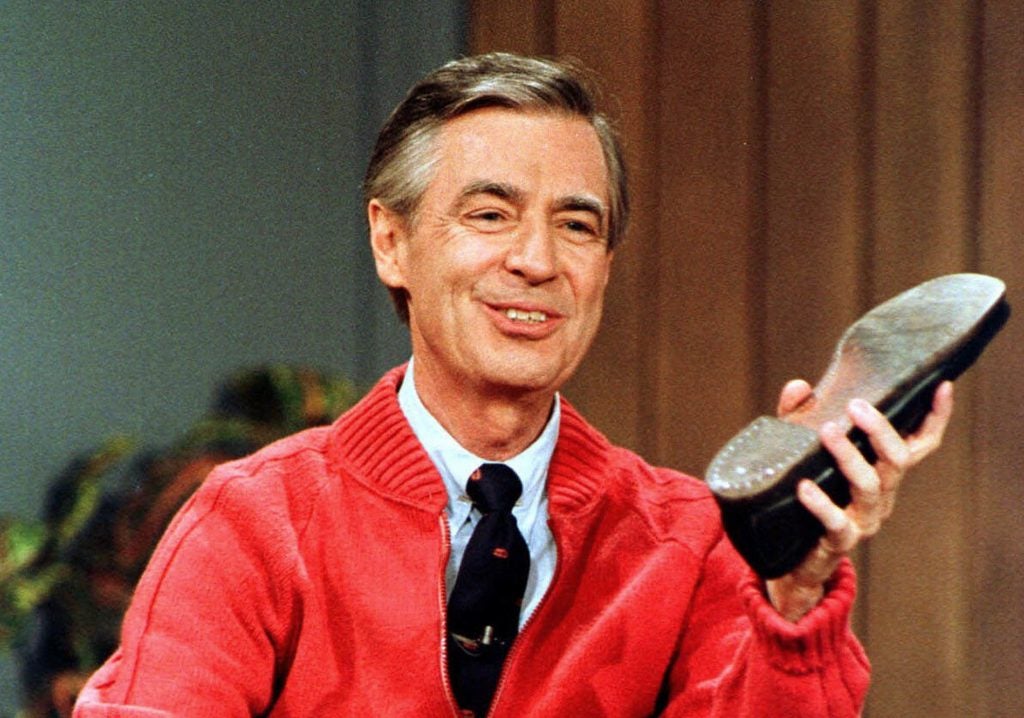

“I have always wanted to have a neighbor, just like you

I’ve always wanted to live in a neighborhood, with you”

When I was younger, my little sister and I used to watch Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood every single week at our grandparents’ house. We knew the name of every character in the Land of Make Believe. We knew every single word to the opening song. Mostly, we were enthralled by this soft-spoken old man in knit sweaters who wanted to be our neighbor.

To us, Mr. Rogers was the ultimate neighbor.

But since then, my understanding of being a neighbor has gotten a little more, well, complicated.

This past summer, I moved into a West Philly apartment with two of my best friends. That made me a single data point among the thousands of young people who relocate to the city every year. When I ask those others why they came to Philly, our answers are similar: affordable housing, access to public transit, proximity to other large cities, a thriving arts and culture scene.

But it isn’t that simple. A quick search on any West Philly Facebook group yields dozens of discussion threads on housing inequality, economic segregation, forced displacement, and more — many issues caused by students and young professionals (like me) moving in and crowding out. It’s such a prevalent phenomenon, in fact, that commenters have a specific name for it: “Penntrification.”

That doesn’t mean it’s limited to West Philly neighborhoods; other recent graduates I know have moved into apartments in Fishtown, or Queen Village, or Graduate Hospital. But the fact remains that, as a Philly transplant, I’m implicated in the conversation of changing neighborhoods and community shifts, whether I choose to engage it or not.

And so I’ve been asking myself: WWMRD (what would Mr. Rogers do)? And what does it mean, exactly, to be someone’s neighbor?

‘No way not to be a gentrifier’

Philadelphia’s one of the most racially diverse major cities in America, but also one of the most segregated. It ranks third in the country for income inequality, and remains the poorest of the country’s large cities. That doesn’t mean that the city needs new voices to create change – instead, it means the voices already here have been doing the work all along.

There are people who have been organizing and acting within these neighborhoods for years.

Most longtime residents are neither powerless nor uninformed about the issues that face their community. The neighborhood was here before me. It’ll be here after me, too.

Still, it feels as if to fully engage in my community, I’m going to need to question my own position within it.

A recent research paper by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia defines gentrification as “an increase in college-educated individuals’ demand for housing in initially low-income, central city neighborhoods,” which seems to be a pretty standard definition; it’s descriptive, objective, and succinctly explains a very real phenomenon in cities across the nation. Which brings us to the real question: what do we do about it?

One article explained gentrifiers’ desire to reframe, morally disengage from, and/or displace responsibility for their own role in neighborhood change. Another argued that there’s “no way not to be a gentrifier,” since the housing market is set up to increase inequality rather than reduce it. Still, others think that discussions about gentrification only further obscure actual issues of spreading poverty and minority isolation, and argue that we should retire the term altogether.

So maybe the more important question is: if I’m moving into a new neighborhood, what identities/privileges/resources am I bringing into my new space? What power dynamics am I introducing? How am I engaging with them?

Easy to move in, harder to be a good neighbor

Or maybe I’m overthinking it.

When I ask my friends and my coworkers what it means to be a good neighbor, their answers mostly hinge on, well, being a decent person: holding the apartment building door, bringing in the mail, resolving conflict in person rather than by calling outside authorities, offering to compromise when it comes to shared spaces. Their advice is less about addressing historical injustice, and more about engaging present communities.

And sure, greeting the woman who lives next door isn’t a quick fix for structural racism, just like offering to babysit for the family down the street doesn’t solve centuries of economic inequality. But it’s still important to do those things.

Because we don’t become good neighbors through a single action or vote or protest or panel. We become good neighbors by learning about and participating in the communities we’ve moved into — by consciously and consistently acknowledging the humanity of the people around us.

Besides, I have time. Mr. Rogers sang about his neighborhood for 895 episodes (more than 33 years!) and I’ve only officially lived in West Philly for two months.

So in the meantime, I shop at local groceries. I go to community events. I’ve started working, and social dancing, and saying hello to people on my street. But I’m still figuring a lot of it out.

Because in the end, it’s easy to move into the neighborhood.

It’s a lot harder to be a good neighbor.

—

What does it take to be a good neighbor? Join PlanPhilly and Young Involved Philadelphia on Monday, November 4 at 6 p.m. at the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission for a discussion about changing neighborhood dynamics and how you can connect with your local community in meaningful and authentic ways.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.