Barnes Foundation spotlights its Native American collection for the first time

90 years ago Albert Barnes collected 239 pieces of Pueblo and Diné (Navajo) artwork. They have never taken center stage until now.

During trips to the American Southwest with his wife, Albert Barnes collected Pueblo pottery and textiles.His collection is displayed with other traditional and modern works in the Barnes exhibit, ''Water, Wind, Breath: Southwest Native Art in Community.'' (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Albert Barnes built his international reputation as an art collector primarily on his keen eye for impressionist and Modernist artists, which he started collecting aggressively in 1912. But he is less known for the Native American art he collected later in life.

“Water, Wind, Breath: Southwest Native Art in Community” features dozens of pieces Barnes collected from the Pueblo and Diné (Navajo) people of New Mexico, accompanied by work of contemporary artists from the same region.

Barnes began traveling to New Mexico in 1930 with his wife, Laura, who needed the dry Southwestern climate to recover from a lung infection. There, Barnes became enamored of the pottery, textiles, and jewelry of Pueblo and Diné people, ultimately acquiring 239 pieces.

“I think he loved the sun and the blue sky and the views,” said Lucy Fowler Williams, a curator at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, who co-curated this show for the Barnes. “I think he fell in love with, also, the handmade quality and the cultural mixture that he experienced there.”

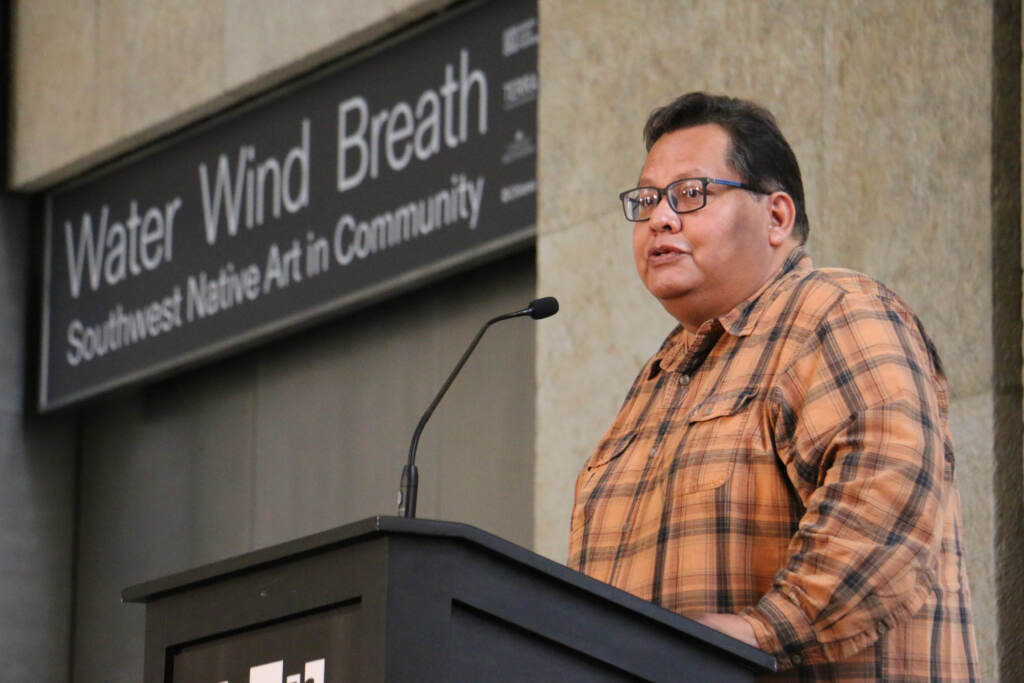

The exhibition was also curated by Tony Chavarria, a Santa Clara Pueblo and curator of ethnology of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He said the Barnes collection shows the bias of the collector: Barnes preferred decoration, largely ignoring monochromatic pottery the Pueblo are also known for.

“It’s a good range of material, although it’s largely painted works. There’s not many redwares or blackwares in there,” said Chavarria. “He liked design. He liked painting. It’s a common attraction for many people.”

Chavarria stressed that the works collected by Barnes were not made for the tourist trade or the art market. Many of the pots show “dipper damage” at their openings, small chips made by a gourd ladle knocking against the lip when a user scoops out water. He said some pieces show what is called “indigenous repairs,” meaning damage that was fixed by the community who used the piece, not by conservators after the piece had entered the art market.

“I think there’s something deeper that was speaking to him because of how he looked at art when it’s made in community,” said Chavarria. “It has a different facet than if it is something being made to be on display.”

During Barnes’ lifetime, few of the pieces ever went on public display. When the Barnes Foundation moved into its new building in 2012, several Pueblo pieces were displayed in cases downstairs, near the gift shop, auditorium, and cafe.

The architects of the new building included a nod to Barnes’ passion for Native American art: Tod Williams and Billie Tsien designed the long seating upholstery with patterning inspired by Pueblo textiles.

The curators believe Barnes was attracted to the pieces, in part, because they came out of a language of symbols and techniques that are unique to a particular community. However, they are not convinced Barnes appreciated the cultural and historical forces that shaped pottery and textiles, in particular colonization by Spaniards and Americans.

For example, most of the storage jars were made to be a certain size, in order to transport a specific amount of corn to Spanish conquerors in the 17th century. The Spanish imposed forced labor on the native Pueblo and Diné, and taxation in the form of 1.5 bushels of corn. The size of their pottery came out of that system.

The Pueblo successfully rebelled against their conquerors in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, killing about 400 Spaniards and driving them out of the territory. However, 12 years later the Spanish returned and reasserted control over the region.

Much of the work in the show is woven or painted in patterns representing the balance between earth and sky, and the spiritual forces of wind and water. The title of the show comes from the Tewa Pueblo concept of Po-wa-ha (wind, water, breath) as the flow of energy that animates all life. That energy is depicted, for example, in spirals and crosshatches painted in the pottery, and by the contrast of materials in the jewelry.

“You get that idea that these things weren’t made in a void or just made for sale, but they were part of a continuing, and ongoing, and long-lasting practice,” said Chavarria.

The curators augmented the Barnes collection by bringing in a few older pieces from the Penn Museum dating to the 18th century, and some very modern pieces from as recently as last year. “Pin-da-getti (Strong Heart)” (2021) by the Santa Clara Pueblo sculptor Roxanne Swentzell, is a kneeling woman wearing a dress made for ceremonial dancing with one hand on the earth and the other on her heart, showing a connection between the two.

Another contemporary artist is Virgil Ortiz, whose work often depicts a blind, woman archer named Tahu. Ortiz invented Tahu and a band of blind women archers as heroes of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, defeating their enemies with their deadly aim despite wearing black bands over their eyes. Garcia revisits the characters in photography, video, and sculptural works.

“Wind, Water Breath” features Tahu twice: in a large-scale photograph of a trio of blind archers aiming their arrows directly at the viewer, and as a smaller tabletop sculpture depicting Tahu in true superhero fashion: wearing high-heeled thigh boots.

Tahu is displayed in the company of artist Jason Garcia’s comic book cover made from fired clay, “Tales of Suspense: Behold Po’Pay” (2016), showing the leader of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, Po’Pay, as a pop culture superhero.

Chavarria says the traditional Pueblo and Diné art lends itself to contemporary pop culture and comics, as both tell stories through an accepted language of visual symbols.

“There’s a visual language in native art, in textiles and jewelry and pottery, that has a meaning for a society within our villages,” he said. “These things are reflected in the art, those made in the past and made today.”

“Water, Wind, Breath” will be on view at the Barnes Foundation until May 15.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.