Can hiring women police officers make communities safer?

Philadelphia and other cities saw domestic violence reported more often, and repeat incidents reduced when more female officers were added to the force.

Listen 07:13

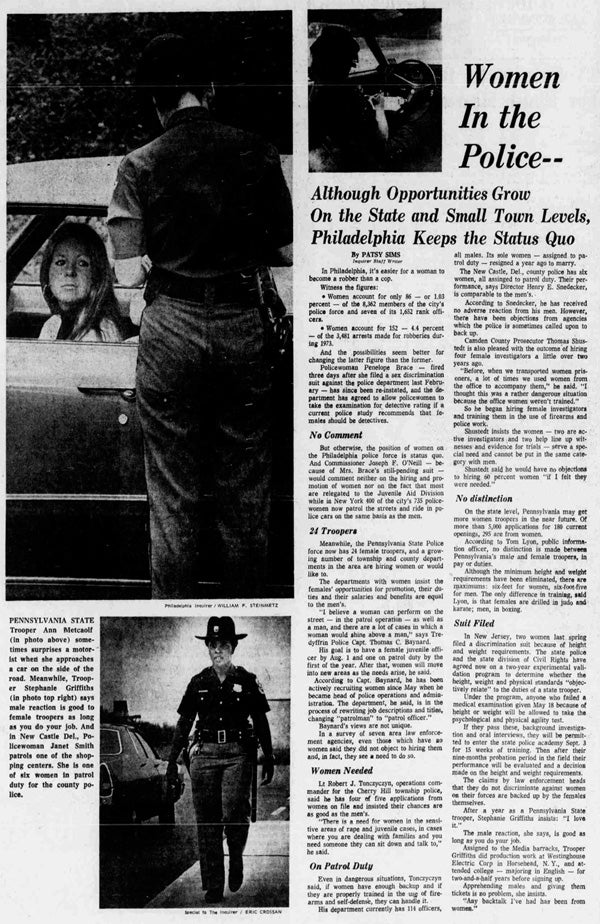

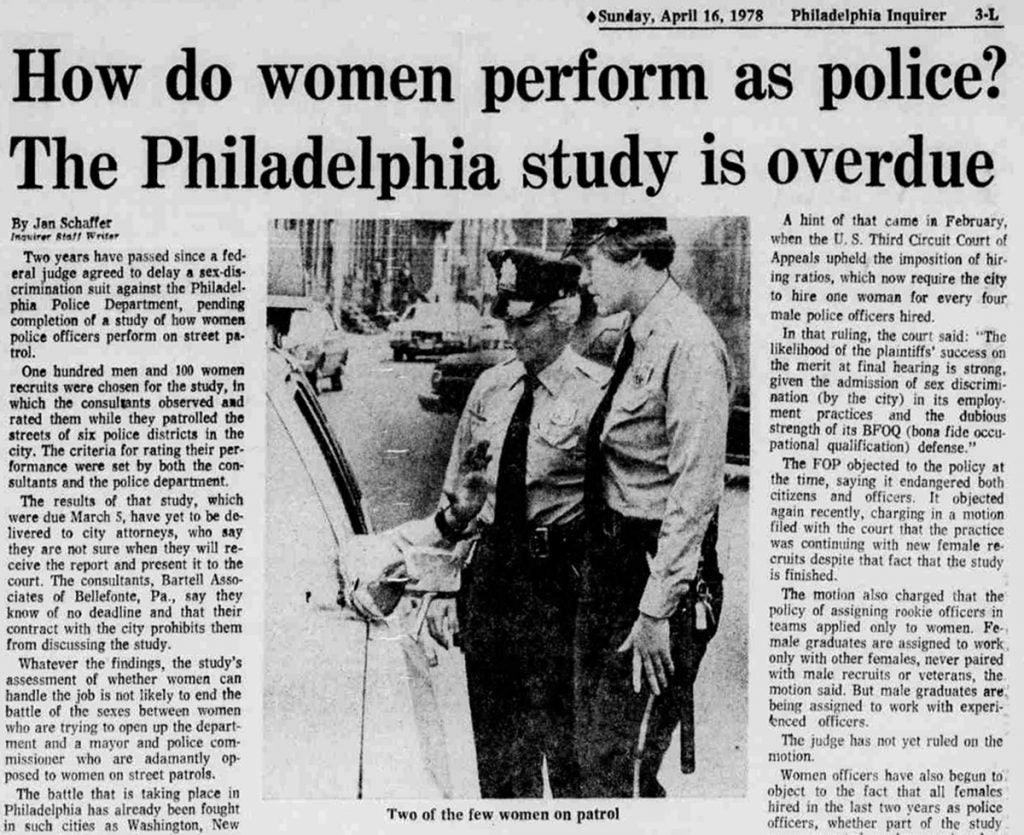

Philadelphia police officer Maureen Rush in 1976 at the 3rd District in South Philadelphia, when she completed police academy training. She then received her permanent assignment to the 25th District in North Philadelphia. (Image courtesy of Rush)

Growing up, Maureen Rush never dreamed of being a cop. As a woman, it didn’t even occur to her that she could be. When she graduated high school in 1971, Rush got a job working at a bank in a downtown Philadelphia subway concourse, and she got to know the police officers who patrolled the area.

“The Philadelphia police were absolutely convinced that we were gonna get robbed every day,” she said. “There was gonna be a bank robbery a day.”

The police had reason to be concerned: Around that time, there had been a series of attacks in the subway station — women being dragged into the basement and assaulted. Because of that, Rush said, the officers would come in each day and sign a daily log at the bank to show they were checking on the employees there. Rush, an animal lover, started stocking treats for the police dogs they brought in with them.

“That turned into friendship,” she said.

One day, the officers came into the bank to sign the log as usual. But this time, they had a woman with them. She wasn’t in uniform — she might have been wearing a business suit and high heels, or maybe just jeans. She looked like any other woman taking the subway.

It turned out, she was a police officer.

Rush was shocked. The officers explained that they employed a very small cadre of women who mostly did administrative tasks: They logged paperwork for missing-person reports and stolen property. Except every once in a while, they’d say they needed a woman to be a decoy.

“And so that day, I met the first rape decoy of my life,” Rush said.

The officers told Rush it was the decoy’s job to lure an attacker, while a SWAT team stood by and watched, ready to catch the assailant. It sounded dangerous, and exciting.

“I thought, `Wow, that is a cool job,’” Rush remembered. That night, she went home and told her family around the dinner table that she had decided: she wanted to become a rape decoy.

“My mother almost fell out of her chair, as you can imagine,” Rush said.

In the early ’70s, there was no other way for a woman in Philadelphia to be a police officer on the street. And, Rush said, at the time that seemed normal to her.

But other women officers and would-be recruits — the ones stuck in desk jobs and decoy positions — were pushing back. Around that same time, a group of them sued the Philadelphia Police Department for sex-based descrimination. They contended that they were being denied access to the force or to better-paying jobs on the basis of their sex.

That was happening nationwide — women were filing class actions, backed by the U.S. Justice Department, to get onto police forces or move up in the ranks. And they won. As a result, police departments across the country were court-ordered to hire more women.

In 1976, Maureen Rush became one of the first 100 women to join the Philadelphia department. Not as a rape decoy, but for street patrol.

And it was not great. The women were met with a lot of resistance, she said.

“Male supervisors would use the C-word, they would use the N-word, they would talk over you like you were not there,” said Rush. “It was clear you were totally unwelcome. They believed that you were taking a man’s job.”

Rush remembers that first winter she was on patrol was one of the coldest on record. She and the other women in her class were often assigned some of the most dangerous neighborhoods. They were given the worst shifts, which they would have to walk on foot because women weren’t allowed to ride in squad cars with men.

She recalls those horrible conditions being used as leverage. She and the other women were offered a deal, she said: You can come in out of the cold, dress comfortably, grow your hair out, wear jewelry, paint your nails — if, the supervisors said, you sign a statement saying women aren’t cut out for foot patrol.

Rush refused. She and most of the other women officers stuck it out. And the fact that they did — has changed police work for the better.

Women cops and domestic violence

In a recent study, researchers out of the University of Virginia examined the period after major American cities added women to their police departments — some by mandate, some on their own. They found that when a city added more female officers, that led to a significant and substantial increase in the rate at which domestic violence victims reported their crimes to the police.

Cases of repeated domestic violence, in which a woman called the cops multiple times, also went down, as did incidents of partner homicide.

The researchers didn’t examine why rates of domestic violence went down when women were added to the force. But they had some ideas:

“It’s possible that female victims might be more willing to call the police and seek help if there are female officers there,” said Amalia Miller, who led the research.

This notion — that more women police officers spurs higher rates of domestic violence reporting — has been borne out internationally. India and Brazil, among other nations where rates of violence against women are high, have been experimenting with women-only police departments for more than a decade.

Reporting rates could also have gone up, and serious incidents down, because women officers were taking domestic violence seriously, Miller said. At a time when domestic violence was more likely to be treated as a private matter between partners, women officers were treating it as a crime.

More than a ‘domestic disturbance’

Renee Norris Jones was in an abusive relationship in Philadelphia in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

She remembers what it was like when she would call the cops on her then-husband while he was beating her.

“This man is beating me like he is in the ring,” Jones said. “I’m watching this police officer, and he is cleaning his nails going, ‘Mr. Jones, please take your hands off of your wife.’”

She was appalled.

“I’m thinking if you just saw this walking down the street, even a stranger, you’d go, ‘Who is this person, get off of the other person, what are you doing?’ And my husband stopped when he got tired.”

Jones said the officer waited for her husband to catch his breath. She remembers lying near the doorway of her apartment, bruised and bleeding, while the officer walked her husband down the block to the street corner and back for him to cool down. When they returned, the police officer wished them both a good night and left.

When Maureen Rush started as a police officer, she’d respond to those kinds of calls. She’d go in with a male officer, and they had a plan.

“It always made sense from the beginning that I would grab the male and the male officer would grab the female, take them into separate rooms, and let them vent.”

That might seem counterintuitive, but Rush said they found it worked better that way.

“Having the opposite gender listening to them was almost like, ‘Well, she wouldn’t listen to me, so you’re a female, you’ll listen to me.’”

After 18 years on the force, Rush is now the vice president for public safety and superintendent of police at the University of Pennsylvania.

In her experience, she said, women are particularly well suited for a lot of policing, much of which she describes as essentially social work — not the car chases or gunfights that a lot of people associate with law enforcement.

Researchers have said adding women can cause an entire department to change the way it handles cases, leading to systemic change within a police force.

“You can’t walk around thinking, ‘When’s that guy going to come after me with a gun,” Rush said. “If you did, you’d be on guard. And if you’re on guard, you would recoil from people.”

When Rush became a lieutenant in the Philadelphia Police Department, she was nervous at first when a new class of male rookies was assigned to her squad. But, she realized quickly, times had changed.

“They didn’t see you as a woman lieutenant,” she said. “They saw you as their lieutenant.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.