With nuke plant shutting down, N.J. community inherits 1.7M pounds of waste

After U.S. plan to dispose of spent fuel rods fails, Lacey Township wants compensation for holding the radioactive waste from the Oyster Creek plant.

Listen 5:32

Oyster Creek was New Jersey's first nuclear generation station, opened in 1967. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

As nuclear power plants around the country continue to shut down — 20 reactors are already on their way out, and several more are expected to follow — questions remain about what to do with the nuclear waste they leave behind.

The U.S. Department of Energy made the commitment to remove and dispose spent nuclear fuel from reactors starting in 1998, but a federal plan to store that waste at Yucca Mountain in Nevada never came to fruition. And there are no plans in place for a permanent spent fuel repository.

Meanwhile, communities hosting nuclear plants — including Lacey Township, New Jersey — face an uncertain future. Exelon’s Oyster Creek nuclear generating station, the oldest operating in the country, will retire in October. The plant, which sits alongside Barnegat Bay, in Ocean County, has served as the town’s main economic driver for 50 years. Residents are anxious about what will happen next.

“Is it going to bring the town down? As far as empty houses, … lost business and things like that,” asked Richard Rom, community president of Pheasant Run, a senior complex with more than 400 residents. “I’m concerned.”

Approximately 300 of Oyster Creek’s 490 employees will keep their jobs during the decommissioning, closure and cleanup process that could take several years, said Exelon spokeswoman Suzanne D’Ambrosio. The company will offer the others positions at other facilities. The plant’s payroll is $68 million, according to D’Ambrosio, and about 100 of its employees live in Lacey, a township with 27,644 residents.

Much more is at stake than jobs.

Rom and other residents benefit from the plant even if they don’t work there. Every year, the plant pays Lacey almost $2.7 million in property taxes, and the township also gets $11.2 million in annual energy tax receipts. It adds up to savings of $2,000 to $3,000 a year on property taxes compared to residents in neighboring municipalities.

“That was really the whole attraction to this community to begin with,” said Regina Discenza, former school board member who moved with her family to Lacey more than 20 years ago because of the low taxes.

Now she’s worried taxes will go up, people will move out, and property values will drop.

“A lot more ‘For Sale’ signs went up since [the plant announced its retirement] because people aren’t going to stick around for what happens afterwards,” Discenza said.

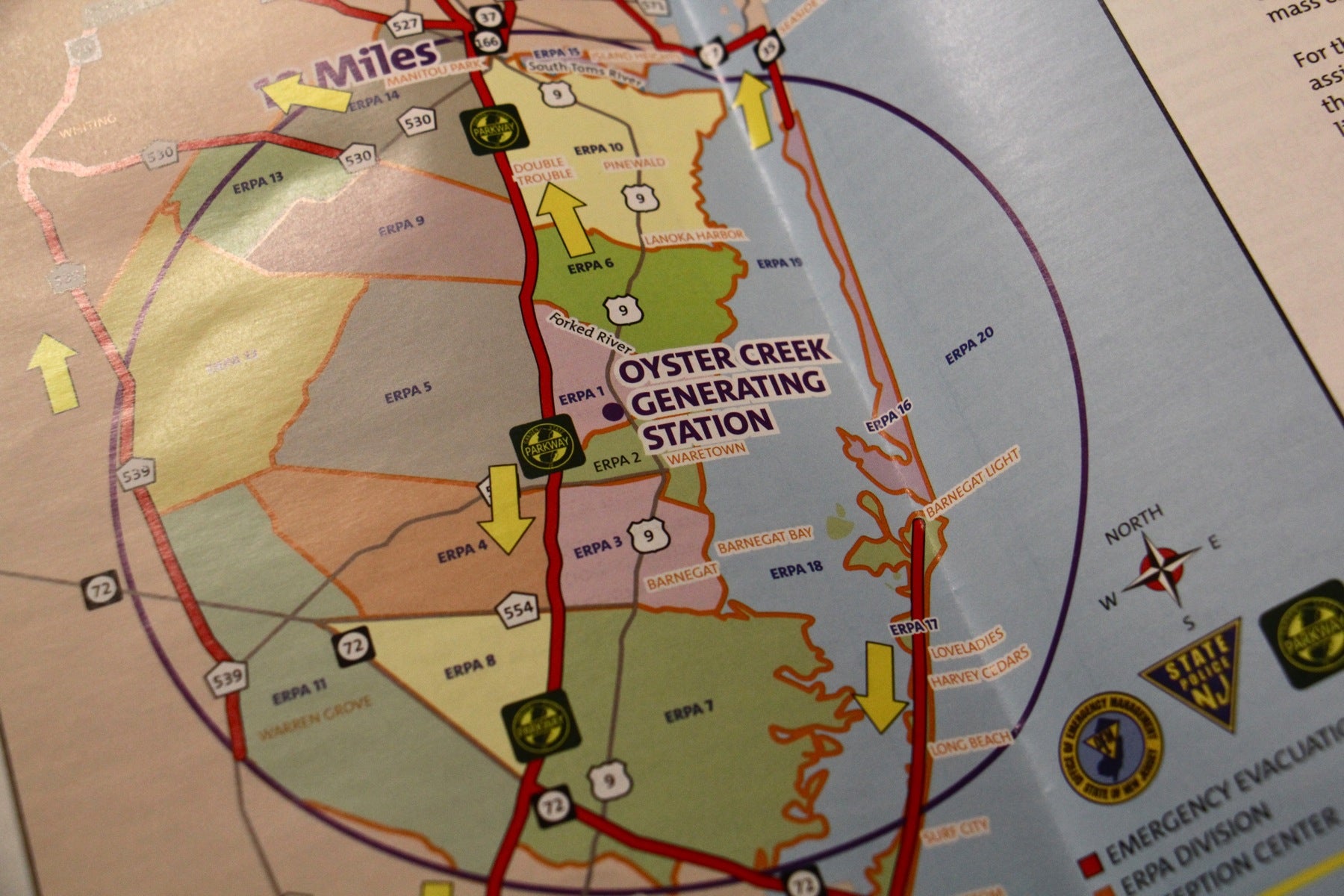

But Lacey is not only losing the economic benefits of hosting the nuclear plant. The township will be stuck with 753 metric tons of nuclear waste because the U.S. has no plan for its disposal. Oyster Creek’s used nuclear fuel now goes to the plant’s spent fuel pool, a specially designed area where the fuel cools for five years. After that, it’s moved to dry cask storage in metal canisters safely contained within a massive concrete structure.

Nevada: No, thanks

Gary Quinn, Lacey’s former mayor and a current committeeman, said the town never anticipated having to deal with the spent fuel, which stays radioactive for hundreds of thousands of years.

“When it was first built, it was never agreed upon that it would become a spent fuel storage facility — which … at this point in time appears to be what we’re facing,” Quinn said.

For more than a decade, the federal government collected billions of dollars from plant owners and ratepayers to pay for permanent storage at Yucca Mountain, but Nevada policymakers successfully blocked that plan.

In response, most U.S. nuclear plant owners sued the federal government for failing to honor its commitment to remove the radioactive waste from their plants. They won, and the government was required to pay Exelon and other plant owners for the cost of keeping spent nuclear fuel in their sites.

Quinn said host communities also deserve to be paid.

“Our feeling is — and we spoke with other municipalities around the state that are host communities to these facilities — that if we’re going to be keeping this fuel in our town, we certainly should be receiving some of the compensation that is currently being paid by every single ratepayer to the electric companies around the country,” he said.

There is no way to replace the shuttered nuclear plant with any other business, Quinn said. Even if Exelon cleans the site as it is required to do — no one wants nuclear waste in their backyard.

“It will be very difficult to build any kind of a major residential or commercial or any kind of development, on a site where you have concrete casks sitting next to the parking lot that are storing spent fuel — it just doesn’t work.”

Community costs left out of debate

Christina Simeone, director of policy and external affairs at the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, said the federal government should be paying Lacey and other host communities some kind of rent.

“I think the communities are getting shortchanged, because the nuclear plant operators are getting compensated from the federal government for their investments in building the infrastructure needed to safely store the waste on site,” Simeone said. “But the communities are not getting paid for their services as waste host communities.”

It’s a growing problem nationwide. As the low-cost natural gas industry continues to grow, more and more nuclear plants struggle for revenue. In March, electric utility FirstEnergy announced it will close three nuclear plants in Ohio and Pennsylvania, citing “market challenges.” New Jersey, finally passed a bill to give a $300 million per year subsidy for two nuclear power plants operated by PSEG, the state’s largest electric utility.

Most of the arguments to keep the plants open address the desire to support nuclear power because of its zero carbon emissions and the need to address climate change. But Simeone said she wonders why the debate is not addressing imposition of new socio-economic costs and risks to communities that host nuclear plants.

“In the process of talking about subsidies to compensate these plants for the environment attribute of zero carbon, it’s very surprising that there’s not a discussion about the waste that’s accumulating on these sites,” she said.

Even if the federal government is responsible for long-term disposal of spent nuclear fuel, Simeone said, the states still must protect those communities. According to the Nuclear Energy Institute, Pennsylvania is second only to Illinois in its accumulation of nuclear waste; New Jersey is 10th.

“Because we haven’t done a good job, there’s a real possibility that we lose low carbon power, and this waste just becomes stranded and these communities are decimated — that seems like a really bad outcome,” Simeone said.

Congressional solution stuck in committees

Last year, bills authorizing federal funds to compensate Lacey and other communities for storing the nuclear waste were introduced in the U.S. House and Senate. The Stranded Act of 2017 establishes that — because the federal government failed to keep the waste — the communities hosting nuclear plants are “interim nuclear waste storage sites” and should be paid what the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 set as a rate for states operating waste sites: $15 per kilogram of spent nuclear fuel.

In the case of Oyster Creek, which by the end of 2018 will have approximately 1.66 million pounds of nuclear waste, that would work out to $11.2 million a year for Lacey Township. That’s exactly what the town could be losing in energy tax receipts.

But the bills, which have been referred to committees, have gained no traction.

Meanwhile, the Prairie Island tribe in Minnesota negotiated payments directly from a plant owner. And two proposals for interim spent fuel repositories are under review, one in New Mexico and one in Texas.

Quinn, the Lacey committeeman, said because the original plan to store the nuclear waste in Nevada is not happening the money should go to the de facto storage sites like Lacey Township.

“Why is it that billions of dollars were spent in Nevada to be able to build this and be able to store this material safely, whereas every other community throughout the country that is doing the Nevada job now has received no compensation whatsoever?” Quinn said.

But right now there’s no guarantee the town will get anything but the radioactive waste, which sits in a concrete structure, next to a parking lot, a few miles from the beach.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.