In violent times, West Philly man lifts mood by bringing water guns to kids worldwide

Gabriel Nyantakyi is raising money to expand his effort — called Waterarms Over Firearms — in Philly and Chicago, two cities plagued by gun violence.

Listen 2:48

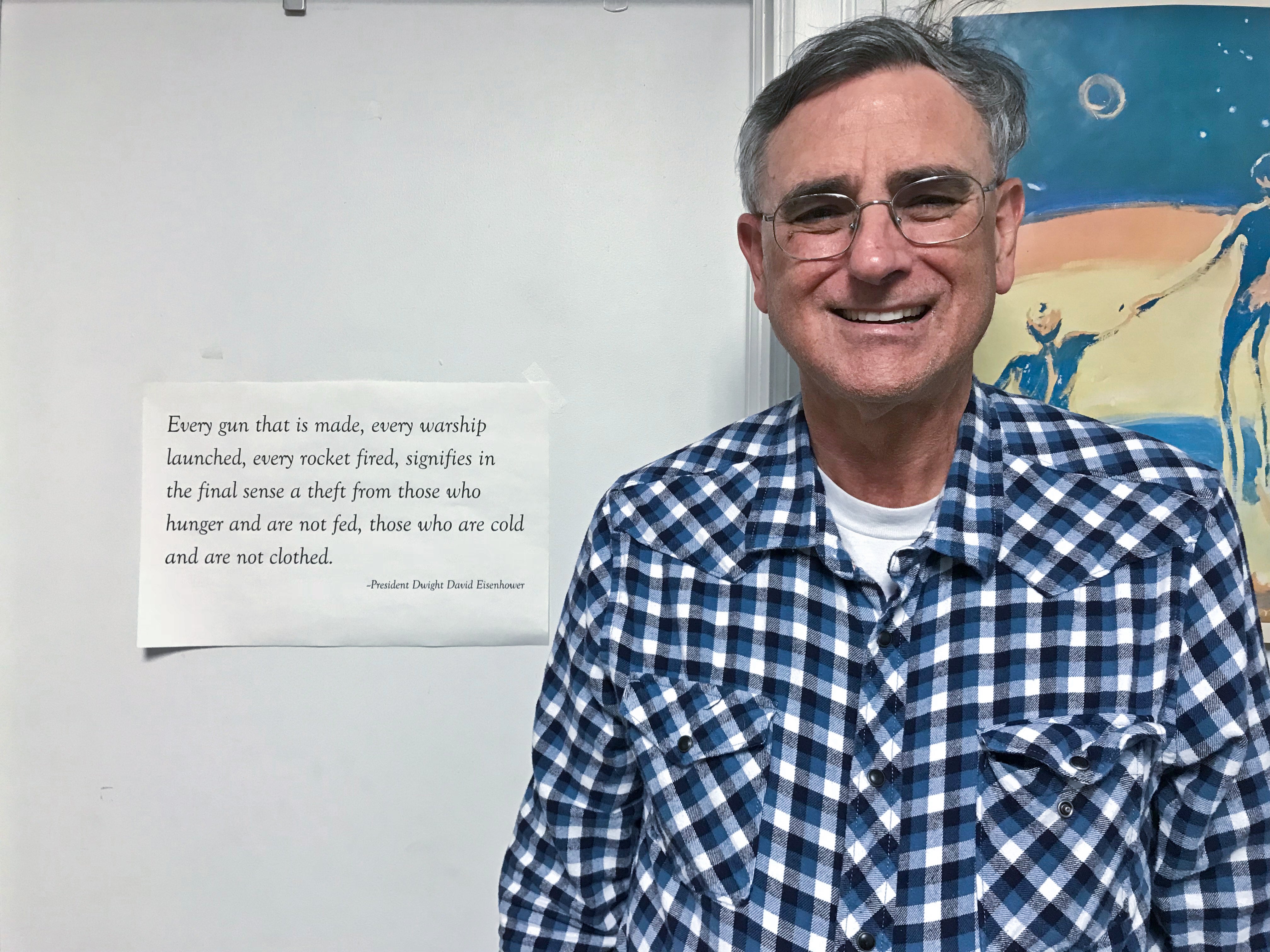

Gabriel Nyantakyi collects super soaker toys and orchestrates water play days all over the world. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Gabriel Nyantakyi is besotted with Super Soakers.

The West Philadelphia man found so much joy in water guns as a child that he became an avid collector — and even has a Super Soaker tattooed on his stomach. Several years ago, he began giving Super Soakers out to everyone from kids in his own hardscrabble neighborhood to young Syrian refugees and other children he encountered during his travels in Iraq, Ghana and Turkey.

“I have some keepers, because I want to play too!” he laughed.

Now, he’s raising money again to expand his effort — called Waterarms Over Firearms — in Philly and Chicago, two cities plagued by gun violence.

The idea, besides bringing kids joy, is to redefine guns at a time when shootings dominate the headlines, he said. Brightly colored, unrealistic-looking Super Soakers have a “metaphorical power” that he hopes can mitigate the damage real guns have done to many neighborhoods, especially in inner cities, he said.

“This is a gun that the whole purpose is to have fun, and the outcomes are wholly positive,” said Nyantakyi, 35, who works as a handyman, dance and archery instructor, and driver for the nonprofit Food Connect. “It’s a gun that shoots water, the thing that’s the essence of life. There’s a poetry there, a message of hope, that I wanted to share.”

He sees his crusade as a sort of psychological sublimation in a gun-obsessed country.

“Guns have proliferated in the area and the culture so much, it’s become normalized, and people have become so numb and desensitized to gun violence,” Nyantakyi said. But “you can take negative behaviors and link it to something positive and harmless as a way of a therapy. This changes the narrative. It’s small, but it’s something within my means to do. This is how I want to contribute.”

Nyantakyi also aims to organize a youth workshop exploring the scientific principles behind Super Soakers’ technology and encouraging participants to design their own water arms.

With the slaughter in Parkland still a fresh wound, not everyone shares his optimistic zeal.

Fake guns have been a serious concern among gun-control activists since at least November 2014, when police in Cleveland gunned down 12-year-old Tamir Rice as he played in a park with an Airsoft pellet gun.

Lately, some worry that even a fake gun can create panic or be misconstrued in today’s climate.

Since Parkland, Walmart announced it plans to end sales of Airsoft and toy guns that resemble assault-style rifles. In Ridgewood, New Jersey, school officials have encouraged students to quit playing an annual “Dart Wars,” a months-long battle in which students ambush one another with Nerf guns around town. And some schools are cracking down on a popular “assassin game,” in which kids use Nerf or other fake and water guns to attack each other.

“You don’t want to be encouraging belligerent play between young people, and things that actually shoot projectiles could do that,” said the Rev. Robert Moore, executive director of the Princeton, New Jersey-based Coalition for Peace Action. “You have to think of the various ways that people might encounter this, especially in a school setting where large numbers of youngsters have been killed.”

Still, Moore, 67, has many fond memories of playing with a water gun during his childhood in West Lafayette, Indiana.

“I got in trouble when I brought a squirt gun to my high school on the last day of school,” he laughed. “The principal didn’t like it at all.”

“I can see that they’re fun, especially in the warm weather,” he said. “Why not run and play (with a water gun)? In general, outside the school setting, I don’t see any significant problem. When it’s used in context of a school, though, there is a little more of a gray area there. Sensitivity has been heightened in our schools, and that may be a good thing. But it has a bad side to it, because we don’t want this to be the new normal.”

Celebrating black scientist’s creation

But Nyantakyi said his crusade has benefits that surpass spreading joy.

The Super Soaker celebrates black excellence and serves as inspiration for children of color, because it was invented by a black man, he said. Former NASA engineer Lonnie Johnson created the Super Soaker, which he first called Power Drencher, in the 1980s.

“That’s also inspiration for me, that it was this black scientist that developed a gun that changed the world in a positive way,” Nyantakyi said. “I’m just proud that a black man did this. He was able to bring joy to a lot of people. It was a beautiful invention, and I try to let people know that piece of history.”

Nyantakyi understands the sensitivity to any sort of gun, even plastic water-blasters.

But anyone demanding that kids put their Super Soakers in storage “probably hasn’t been in a Super Soaker fight in a long time,” he said. “It’s fun!”

“If you’ve been displaced by a civil war, or you’re in a place where every day in the news you hear of people dying because of gun violence, it’s a beautiful thing to hand a kid a water gun and see, within a few minutes, them shooting themselves in the mouth like: ‘I was so thirsty and now I’m not anymore,’ ” he added. “In an ideal world, yes, children would be protected from gun violence and firearms. But it’s going to be a struggle for us to remove firearms from our culture. This is a way to shift our focus in a more positive direction.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.