‘Too sick to rest’: How long COVID helped one doctor learn to slow down

For a Philadelphia physician, rest seemed out of the question during the early part of the pandemic. But she learned an important lesson about the need to slow down.

Listen 19:20

Shreya Kangovi is the founding Executive Director of the Penn Center for Community Health Workers. | Courtesy of Penn Medicine

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

The persistent buzz of hovering helicopters cast an air of agitation over Philadelphia during the summer of 2020. For Shreya Kangovi, the buzzing was inside her head, too.

“Saturated. COVID. Unrest,” Kangovi wrote in her journal in June. “I’m sick. I have a helicopter in my brain.”

The pandemic was in full swing, demonstrations against racism were erupting in the streets of Philadelphia, where she lives, and Kangovi felt like she was falling apart.

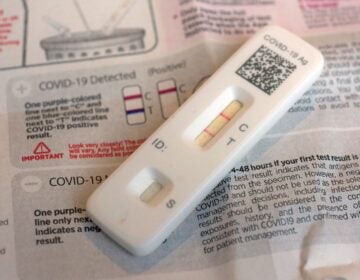

She had gotten COVID-19 in April, and, two months later, she was still not feeling better.

But Kangovi didn’t feel as if she could slow down or take a break. Her work was more intense than ever: A family medicine doctor, she not only sees patients at a federally qualified health center, she also runs a center for community health workers at the University of Pennsylvania.

Community health workers care for individuals in their own neighborhoods. They set health goals with patients and figure out how to achieve them. That can mean anything from making certain medical appointments, to battling an eviction notice, to planting a garden.

With so many questions about COVID-19 and everyone stuck at home, those services were in high demand. Kangovi had to figure out how to reorganize her entire operation so that her team could do the job safely. She also felt as if that moment could be a huge opportunity for her cause to gain wider public recognition and support.

“There were bread lines, there was massive economic insecurity, and there were mental health crises,” she said of the early months of the pandemic. “These are the kinds of things that community health workers address.”

For Kangovi, it was not a time to take a step back.

But as she tried to power through her lingering symptoms, they only got worse. The less she rested, the more she needed to and the harder it was to function in her day-to-day life.

At the time, no one had even identified long COVID as a condition, leaving Kangovi in the dark for answers, at times doubting whether her symptoms were even real.

And so she pressed on, fighting for her cause and caring for her family in the midst of a public health crisis, exhausting every last ounce of energy, until her only option was to rest.

‘Trapped in a snowglobe’

By May, Kangovi’s hair was falling out. Her sinuses were inflamed; she was always exhausted. She felt a constant buzzing, not just in her head, as she noted in her journal, but a restlessness coursing through her body. She noticed that she had written in her notebook backwards — something she’d never done before. She had trouble recalling words: doing so felt like an engine revving on neutral inside her head. Her brain function felt muted, or muffled — as if a soft slice of bread was coating her brain.

But the single biggest issue plaguing Kangovi was her sleep.

Normally, she was a “great sleeper,” yet Kangovi’s sleep was now shallow and restless.

“My sleep felt like dozing on a bus,” she recalled. “I would drift off and still be able to trace the thought pattern that I was having before I had fallen asleep. I didn’t dream. I just kept thinking,”

When she did fall asleep, she would awaken with a sudden, electric jolt of energy and be wide awake. She estimated she had these interruptions roughly 20 times a night.

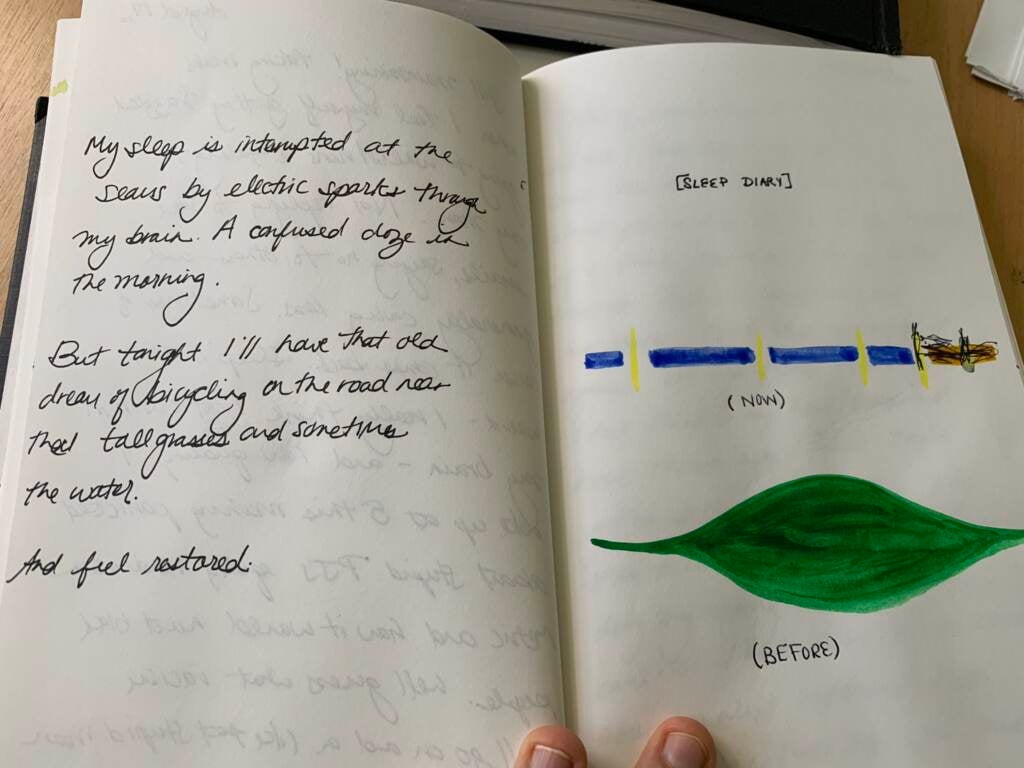

In her journal, Kangovi drew a diagram of how she imagined her sleep looked:

A horizontal line, broken up by bright yellow electric jolts every hour or two, with a confused, restless period in the early morning hours. Beneath that image, she drew a picture of how she envisioned her old sleep: a ballooning green leaf, full in the center and tapered at the ends. She wrote she hoped to dream of bicycling near the tall grasses and along the water. But that sleep did not come.

Kangovi’s symptoms persisted while her work was still remote, so she kept up with her Zoom meetings. She knew something was wrong, but nobody else did.

“I felt like I was trapped in a snow globe,” she said.

During the first months of her illness, long COVID, or post-COVID conditions, hadn’t been identified yet. So there was nothing for her to point to and say, “I have that.”

Sometimes, she wondered if her symptoms were even real. She did have a lot on her plate. On top of her work, Kangovi also had a 1- and a 2-year-old at home.

“When I would complain to friends or family members that I was exhausted, they’d be like, ‘Hashtag mom life!’” Kangovi recalled.

She thought maybe that was just what she was supposed to be feeling. After all, she reasoned, she treated patients who dealt with much worse.

“People who’ve lost family members and they still take care of their kids and they get out of bed and they take the subway to work,” said Kangovi.

“I was like, I’m doing this.”

That attitude is how Kangovi has always approached her work, according to her colleagues.

“Her famous thing is: ‘Do what you say you’re going to do,’” said Mary White, a community health worker who’s worked with Kangovi for over a decade. “Don’t leave people hanging, you know, follow up with them.”

White, who Kangovi considers a mentor, said Kangovi’s perfectionism is appropriate, given the high stakes in their line of work — dealing so intimately with people’s lives.

But, said White, that persistence and drive also led Kangovi to press beyond her own limits, without letting anyone know she was sick.

She didn’t even tell her mom, Sita Kangovi, who lived nearby in New Jersey and whom she spoke with on the phone most days.

Sita Kangovi said she wasn’t surprised her daughter was working so hard during such a turbulent time. Her daughter has always been deeply committed to and affected by social justice work.

She recalled an incident when her daughter was a little girl and some kids on the school bus had stolen an inhaler from another child with asthma.

“She yelled at them and got the inhaler back to the kid,” Sita Kangovi recalled. “She came home crying, ‘I want to help all these people.’”

But it wasn’t until she saw her daughter up close that Sita Kangovi realized just how sick her daughter had been all along.

“I was horrified,” Sita Kangovi recalled. “She had sunken cheeks, deep, dark circles under her eyes. She had lost weight. She’s generally a very tough cookie, but she was very ill.”

Shreya Kangovi still wasn’t sleeping. She knew it was the thing her body needed most to recharge, but it just wouldn’t come. It was wearing on her. She lost her sense of joy. The world faded to a muted gray. She was becoming delusional — she saw rats scurrying across the floor out of the corner of her eye that no one else saw.

Still, she couldn’t nap or rest, so she just kept working. In a sense, she said, she was too tired to sleep.

“It was my Dante’s circle of hell,” she said.

And then one day, the physical exhaustion pushed her to a point that, a year ago, she never would have thought was possible. She called her mom and told her she was going to quit her job. She told her if she didn’t, she actually thought she might die.

That was so unlike her daughter Sita Kangovi knew she had to intervene. She suggested that she and her husband move in with their daughter and her family to help watch the kids and take care of things around the house. Kangovi agreed.

There wasn’t room for everyone in Kangovi’s rowhouse, so she and her husband put their place on the market and bought a bigger home where everyone could fit comfortably.

Sita Kangovi tried to get her daughter to rest by recounting the stories of Hindu saints, which she knows and loves. She told her the story of Ramana Maharshi.

“He always used to say, for individuals to have their own sense of doership is like passengers sitting in a train with their luggage on his head,” said Sita Kangovi. “The train will take you to the destination. The train will take the luggage to the destination, but you might as well take the load off your head and sit at ease.”

Finally in March 2021, after much hand-wringing and concern that she was abandoning her team, Kangovi decided to take a break. Long COVID had been identified at this point, so she could name the thing that was happening to her. She announced she was taking a sabbatical from her job. No one had realized how sick she was until she told them. But they weren’t mad she was leaving. If anything, they just wished she’d done it sooner.

Subscribe to The Pulse

‘Light your own candle, and move ahead’

Very slowly, Kangovi gave in to rest. She started going to the doctors’ appointments she hadn’t made time for before, beginning with a specialist at the University of Pennsylvania’s new clinic devoted to long COVID.

A doctor there asked her to do a memory exercise: He listed a string of five words, and then asked her to simply repeat them back to him. She could remember only one. He gave her a hint: It was a body part. Still nothing. He gave her a few to choose from: leg, arm, or face? She couldn’t recall.

Perhaps the most important specialist Kangovi saw was Indira Gurubhagavatula, a sleep doctor at the Penn Sleep Center.

Sleep disorders associated with long COVID are new, so doctors don’t know much about what causes them. It could be that a small amount of virus is still hiding out in various tissues, and a person hasn’t fully gotten rid of it yet. Another possibility is that excessive fatigue is caused by an prolonged autoimmune response, in which antibodies that fight the virus are also attacking native cells, causing a feeling of shakiness or exhaustion. For some, it could be anxiety.

To get a better sense of what was happening for Kangovi, Gurubhagavatula and her team created a diagram of Kangovi’s sleep patterns called a sleep histogram. It looked remarkably similar to the one Kangovi had drawn in her journal.

They found that Kangovi was spending too much time in the shallow phases of sleep, and not enough in the deep rejuvenating phases. They also noticed she was sliding in between the phases of sleep way more often than normal.

This can happen with other sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy. In that case, instead of waking up in the middle of the night without warning, people can fall asleep suddenly in the middle of the day.

Gurubhagavatula was careful not to jump to conclusions, but wondered if something similar might be happening here: if the virus, or an autoimmune response, might actually have damaged some cells in Kangovi’s brain that regulate the sleep phases.

That sounded right to Kangovi.

“It just felt like my sleep was unhinged at the seams and it was just popping open every time I had to connect to sleep cycle,” she said.

The sleep histogram showed that Kangovi was finally able to enter into a deep sleep by the early morning hours, starting around 6 a.m. But she was rarely able to get there, because that’s when she needed to wake up to take care of her kids. Until her parents moved in.

“Probably the single most useful intervention was having my family, my parents watch my kids from like 6 a.m. to 8 a.m. so I could sleep until 8 a.m.,” Kangovi said.

Once her parents moved in, Kangovi started to sleep more and more. There was a period when she was sleeping up to 18 hours a day.

The idea of building up a sleep debt is a real thing, said Gurubhagavatula: There is a well you can dip into and repay later. But, she said, you can’t live on borrowed sleep forever. At a certain point, you do max out.

Kangovi believes she came really close to that point.

During her time resting, Kangovi did a lot of yoga. She let her mind wander. She relinquished control.

She spent time reading the Gita, one of the holy scriptures of Hinduism. She paged through history books of ancient Hindu art.

One image struck her in particular. It was a sculpture of a man from India seated in the lotus posture, his spindly arms made of fishbone. The caption dated the sculpture to the third millennia B.C.

Kangovi said it was that notion — that beneath her feet lay the remnants of civilizations that had been struggling for millennia — that put her fight for social justice in perspective.

“I’m marching through my day, like all pissed and righteous about the thing that I’m doing right now,” said Kangovi. All of a sudden, that seemed trivial.

She realized she’d been thinking of her own anger and suffering as a way to level the playing field with her patients.

“I wanted to suffer as much as they were suffering, and I just was very privileged and lucky, so my suffering was going to come from just beating myself up over getting the work done,” she explained.

But in her time off, Kangovi realized that suffering for suffering’s sake wasn’t getting her anywhere.

“Don’t worry about all the darkness in the world,” her mother had told her. “You just light your own candle, and move ahead.”

Kangovi is back at work now. She wouldn’t say she’s fully recovered. She still has bad days, bad weeks. But she feels calmer, more balanced. Her mom agreed, and so does Mary White, her mentor.

During the pandemic, the country hasn’t turned its health care system inside out to embrace community health workers as the new model for medicine, as Kangovi had thought might be possible. But when she went on sabbatical, the community health workers on her team did just fine. In fact, they thrived.

She was proud of them. She was humbled. It was the reminder she needed that the world can go on without her. It always has.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.