From slums to sleek towers: How Philly became cleaner, safer, and more unequal

The reinvention of Society Hill in the 1960s is widely considered one of the first instances of gentrification — although no one called it that at the time.

Listen 6:37

A view of Society Hill taken from inside the Society Hill Towers. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Harry Schwartz, 84, remembers when his neighborhood, Society Hill, was one of the poorest parts of Philadelphia. But by the time he moved there as a young lawyer in 1969, things had changed. City planners had fixed up crowded blocks of crumbling old houses and razed a congested, old wholesale produce market to make way for majestic modernist towers. Schwartz and his pediatrician wife were attracted to Society Hill’s architectural gems, tucked among its cobblestoned, walkable streets. Soon, they found themselves surrounded by a community of artists, activists, and young professionals like them.

They loved it. Society Hill allowed them to bike to work and walk to friends’ houses for Julia Child-inspired dinner parties. Today, Schwartz lives in an airy, sun-lit condo in the soaring towers that replaced the old Dock Street Market. His living room windows overlook some of the city’s most coveted addresses.

The reinvention of Society Hill in the 1960s is widely considered one of the first instances of gentrification — although no one called it that at the time. The term was coined in 1964 by a British sociologist to describe the nascent phenomena of the middle-and-upper-class moving into the meaner parts of London. Since then, the term has only become more fraught, hard to precisely define, and often racially loaded. No one wants to identify themselves as a gentrifier, not even a half-century later.

“What happened in Society Hill in our experience, and I speak only from that, was not displacement,” says Schwartz, who moved in about a decade after city government spurred the redevelopment of the neighborhood. “But rather [by the time they moved in 1969], re-occupation and restoration.”

Society Hill’s transformation from one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods in the 1950s to one of its richest by 1970, appears in textbooks today as a model of urban renewal. But in its time, the neighborhood’s rebirth was an isolated instance amid a prolonged and widespread exodus of wealthier, usually white, residents from city centers across the U.S.

No longer. Although America is still a suburban nation, almost every big city in the country has at least a handful of central city neighborhoods that are seeing an influx of wealthier residents and an accompanying increase in housing prices.

“[In the later 20th century] people start marrying later and having fewer children, so you have a rise in the number of single adults, a demographic more drawn to central city living,” says Lance Freeman, Professor of Urban Planning at Columbia University and author of There Goes The ‘Hood.

“You have economic changes, the decline in central city manufacturing, and an increase in service industries that benefit from concentrating in downtowns. After many central city neighborhoods were divested, the conjunction of those forces [left] cheap opportunities to acquire real estate.”

It’s a phenomenon that is a reshaping parts of Philadelphia, bringing new residents, higher rents, and towering gray townhouses to neighborhoods where investment has been scarce for decades. A 2016 study from the Philadelphia Federal Reserve showed that between 2000 and 2014, the city lost 23,628 rental units available at $750 or less per month, with these low-cost units in gentrifying areas vanishing at five times the rate of non-gentrifying areas. There are only a handful of neighborhoods — eight of the city’s 337 residential census tracts — that experienced “intense” gentrification between 2000 and 2014, most of it concentrated in Center City and adjacent neighborhoods, or sections of West Philadelphia closest to University of Pennsylvania’s leafy campus. Yet for many people across the city, the upscaling comes with tricky questions of belonging, along with new economic pressures.

Displacement is notoriously difficult to track, especially because low-income renters move more frequently than the average population. The studies that have come out with conclusive data have found that gentrification is associated with minor levels of direct displacement, but that rising housing costs make it less likely for lower-income people to move into gentrifying neighborhoods. “This represents a form of indirect displacement where vulnerable residents face barriers to entering improving neighborhoods and are relegated to living in more disadvantaged areas,” authors of the 2016 Federal Reserve study wrote. Lower income residents who stay often experience hardship too, in the form of higher housing costs and added strain on their finances, the report noted.

Yet for less vulnerable residents who remain in gentrifying neighborhoods, benefits abound, according to a 2014 study from the Fed. For those incumbent residents, increased financial health came with the influx of wealth into the neighborhood. They were less likely to move than peers in non-gentrifying areas, the Federal Reserve researchers found. While gentrification hasn’t budged the city’s stubbornly high poverty rate, the city’s job growth rate has climbed in recent years, outpacing national averages, and crime rates have dropped. The city’s public schools are making gains and Mayor Jim Kenney is banking on increased tax revenue from property taxes and real estate transactions to cover the school district’s yawning budget deficit.

“It’s hard to say, gentrification is good or gentrification is bad, because it really can play out and affect people in different ways,” says Freeman.

But good or bad may be the wrong question. The towers that replaced Society’s Hill’s old wholesale market aren’t going away and neither are the chic, roof-deck-topped rowhouses sprouting up on weedy lots in neighborhoods like Point Breeze, Kensington, and Northern Liberties. This week, WHYY’s Keystone Crossroads and PlanPhilly teams are examining those changes from the ground up, talking to people on all sides of the issue, exploring its origins and what’s next.

The long flight from Center City

It’s difficult to imagine now, but for most of the 20th century, the urban cores of most American cities were undesirable places to live. “I remember being in kind of a dingy environment,” says Schwartz, recalling a 1940s trip to a Jewish tailor in the neighborhood that would become known as Society Hill. “But apart from that, I never really got down to this area. There was really no reason to come.”

This kind of unappealing vista wasn’t unusual in mid-century Center City or in most American cities. Sooty factories and other industrial uses had risen in the heart of urban communities, where workers could easily access them on foot. Their smokestacks mingled with the coal fires from densely crowded neighborhoods. Raw sewage and other effluent was dumped directly into the rivers, which let off noxious fumes that would nauseate dockworkers. (One of the reasons why highways run alongside the water in Philadelphia and a lot of other cities is that no one really wanted to live nearby.)

The nation largely lacked air pollution controls until Congress passed the Clean Air Act of 1963, and didn’t effectively regulate water pollution until the Clean Water Act was rewritten in 1972. Before then, pollution alone made city life unpleasant, and the suburbs didn’t just promise a yard with white picket fence — they offered relatively smog-free skies.

The mass white flight of the 1950s and 1960s represented the apex and most destructive phase of a long middle-class movement out of the city, as new federally subsidized and racially segregated suburbs were thrown up along brand-new, government-built highways. The astounding growth of these communities, outside the political boundaries of older cities, starved the old urban hubs of revenue. At the same time, crime rates skyrocketed, propelling further flight and new costs for beleaguered cities.

The tower that Schwartz lives in came as a response to that crisis. By 1960, Philadelphia politicians, fueled by a massive injection of federal dollars for urban renewal, were beginning to experiment with how to compete with the suburbs. That year, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, then a relatively new agency at only 15 years old, condemned any property in Society Hill that was vacant or in poor condition. They transferred ownership to a group called the Old Philadelphia Development Corporation which then interviewed potential buyers to ensure they had the wherewithal to fix up or demolish the buildings.

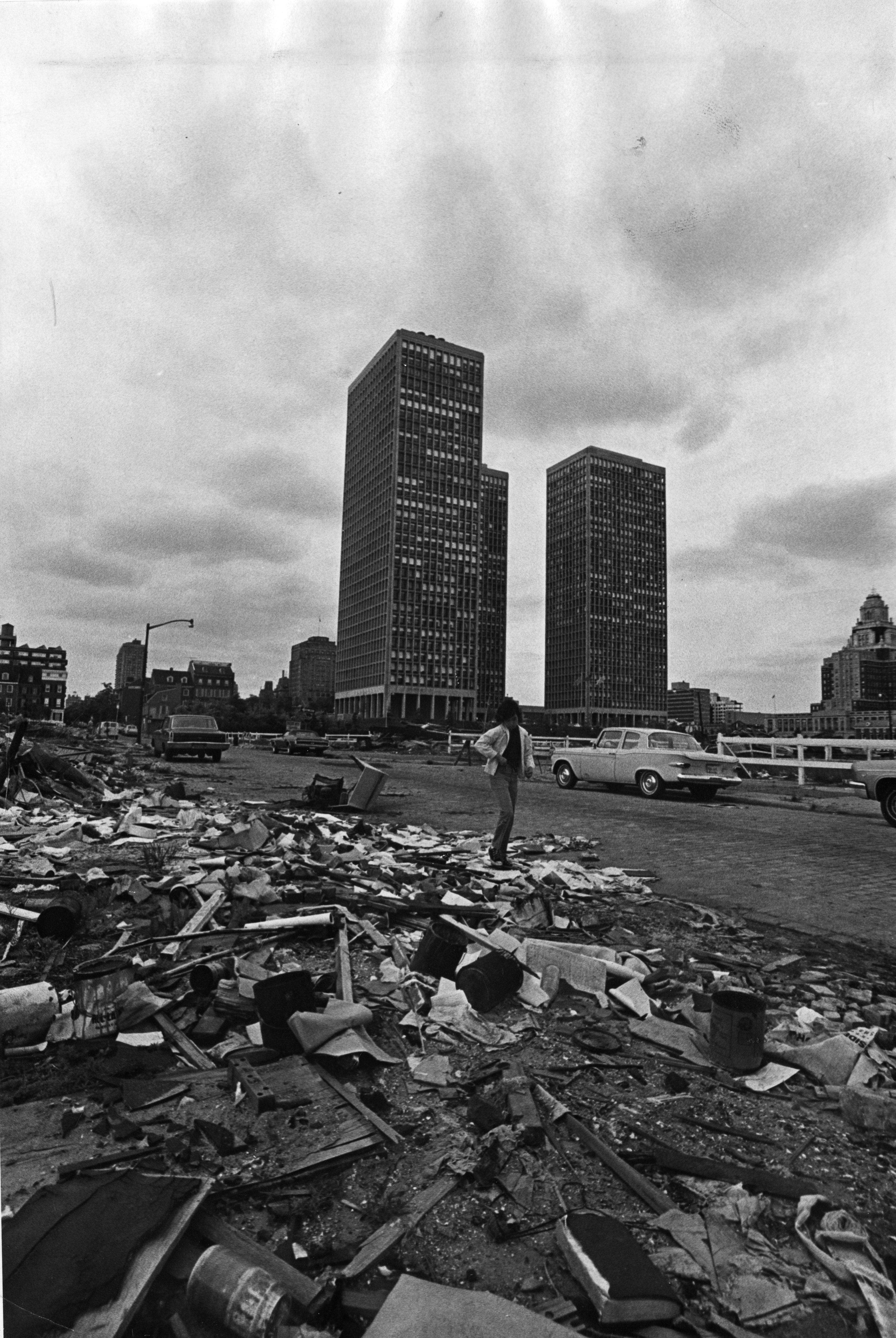

Existing homeowners could keep their homes, but they had to prove they had the resources to repair them. The Redevelopment Authority would claim these buildings and then issue a new deed with a restrictive restoration agreement attached. Planners leveled the Dock Street Market for the Society Hill towers, designed by prominent modernist architect I. M. Pei.

“Society Hill became increasingly exclusively affluent,” wrote Greg Heller, now the head of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, in his biography of Edmund Bacon, the planner behind the neighborhood’s reinvention and many of the city’s other post-World War II redevelopments including Penn’s Landing and Market East.

“In many ways, [Society Hill] was the first true example of the kind of urban gentrification cities across the country have since experienced,” Heller wrote.

Can Philadelphia prove gentrification doesn’t have to hurt?

In hindsight, Bacon’s transformation unfolded in ways that are more transparent than the messy reality playing out in Philadelphia today. Policymakers went into that urban renewal-era reinvention with the understanding, based on the city Planning Commission’s calculations, that 34 percent of existing residents would be displaced. “It was more important to restore this area than to maintain the low-income residents,” Bacon remembered decades later.

For those pushing back against neighborhood upscaling, it was their darkest fears realized in daylight.

To attempt a wholesale clearance of a working-class population in the name of urban betterment would be political suicide for someone in Bacon’s position today. “What we understand today is that the issues that communities face are multi-faceted and deal with a whole variety of not just physical, but social and economic, issues that are tied together and correlated in all kinds of ways,” said Heller in a 2016 interview.

For Heller and his peers in city government, the question is how to navigate that complex web of cause and effect so that Philadelphia can prosper in a way that benefits all residents. Ken Steif teaches urban planning at the University of Pennsylvania. He says Philadelphia still has the opportunity to ensure development happens equitably.

“Look at cities like New York and San Francisco that were in similar places 30 years ago. Trying to find equity in those cities nowadays is almost a lost cause,” says Steif. “We should be figuring out whether Philadelphia is going to undergo the same kind of shock that New York and San Francisco have, and how can we ensure that everyone is better for it.”

The West Philadelphia resident and professor says cities must be more proactive in supporting low-income residents before they are priced out of gentrifying neighborhoods. He points to programs like the Healthy Rowhouse Project, which helps vulnerable homeowners with repairs so they can stay in their homes, and to recent City Council legislation, also designed to help low-income Philadelphians rehabilitate owner-occupied residences. In that way, homeowners can decide whether they want to stay in growing neighborhoods, or cash out their equity by selling close to the market rate.

“We want these neighborhoods to change,” says Steif. “We want neighborhoods to have safer streets, to have better schools, to be true neighborhoods of opportunity, and we want folks of all races and classes to be able to take advantage of those amenities.”

How to get there is an open question. Most community leaders say they want to address gentrification’s negative impacts, yet attempts to do so are often met with resistance. Many experts believe that creating more housing catering to the full spectrum of consumers will help alleviate market pressures and lead to more affordable options. Yet when developers want to build, they face opposition from neighbors. In the city’s most desirable historic pockets, getting approval for projects often becomes a Sisyphean task. A recent proposal to erect a condo tower over a one-story grocery store in Society Hill was scuttled after an enormous community backlash.

The hurdles extend to affordable housing initiatives. Witness, for example, the stalemate in City Council over an inclusionary zoning proposal that would require developers building in dense sections of the city, most of them in already gentrifying Center City and University City, to include affordable units in projects. The city’s controller Rebecca Rhynhart recently announced an investigation into a controversial 10-year tax break for new construction that critics say disproportionately subsidizes the wealthy, while starving the city of tax revenue that would go to support public services and schools.

Rhynhart has said that her study will consider alternatives to the current abatement, including “continuing it only in neighborhoods most in need of investment,” according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Schwartz, for one, understands the conundrum. The city’s investment created the neighborhood where he chose to buy a home and make a life not once, but twice. His family left Philadelphia in 1976, so he could work for President Jimmy Carter’s administration in Washington. He and his wife stayed in D.C. until he retired in the early 2000s. At that point, there was only one place he and his wife wanted to move: Society Hill.

“I wanted to live in the city as we had, because I remembered how good it was,” says Schwartz. “Why not live in a place where we can walk to where our friends live, the way we did before?”

—

This article is the first in a series, “Gentrified: stories of rapidly changing Philadelphia.” The series is a collaboration of PlanPhilly, Keystone Crossroads and WHYY News, supported by a grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.