How redlining segregated Philadelphia

Decades after civil rights laws overruled racist policies that starved non-white neighborhoods of investment, new analysis shows that deep disparities linger.

Listen 6:38

Alex Peay in his North Philadelphia neighborhood (Joshua Albert/Next City)

About a third of the homes on West Oakdale Street between 15th and 16th in North Philadelphia are empty. Six vacant lots interrupt the narrow rowhouse block. On a recent November afternoon, brown tendrils of dead ivy cling tightly to the roof of one abandoned home and blanket the brick below. A thriving colony of feral cats boldly holds court among the piles of litter at the east end of the street, within sight of Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority’s North Philadelphia station.

Nearby there are blocks in worse shape, so blasted that they appear touched by the hand of God or by some implacable force of nature. Closer to Broad Street and along major thoroughfares like Lehigh Avenue stand the faded remnants of North Philadelphia’s 19th-century past.

When Alex Peay moved to Philadelphia from New York City 10 years ago, the scale of the disinvestment astounded him. He now lives about a 15-minute walk from West Oakdale Street.

“I’ve seen it in New York, but not to this scale,” says Peay, who runs a nonprofit called Ones Up, which helps disadvantaged youth learn professional skills. “There are just blocks and blocks of abandoned houses. And you go down Broad Street and notice that at one time that was a busy, high-end area. Now there’s nothing. You’re like, ‘what the hell happened?’”

There are many reasons for North Philadelphia’s desperate state. But one of the most profound can be traced back to an 80-year-old social engineering effort, when the federal government exacerbated racial wealth disparities and housing segregation across the United States.

Beginning in the 1930s, the federal government involved itself in the national economy as never before. But as it struggled to revive the housing market after the Great Depression, it spurned the opportunity to maintain or foster integrated neighborhoods. Instead the federal government encouraged mortgage lenders to withhold credit from older urban neighborhoods, immigrant communities and, especially, areas where African-Americans or other people of color lived.

The process came to be known as “redlining,” because of the way that banks and federal agencies marked maps of the neighborhoods where mortgages should be withheld, chalking them off from the rest of the city with red ink. North Philadelphia and its cousins across the U.S. were choked off from credit, the lifeblood of any healthy community.

“The federal government may not have had their hand in every transaction, but they are the ones who shaped the commercial lending culture across the country,” says N. D. B. Connolly, professor of history at Johns Hopkins University. “It was a feedback loop between the federal government and the local level.”

In many parts of Philadelphia, the cycle remains largely unbroken today.

How the new deal segregated Philadelphia, and America

The New Deal gave birth to an array of federal agencies intended to stabilize the capsizing housing market, and create jobs in a moribund construction sector and shelter for those in need. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) staved off foreclosures by refinancing hundreds of thousands of existing mortgages, while the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) jump-started housing construction by insuring millions of mortgage loans issued by skittish private lenders. During the same period, the federal government began to finance the construction of public housing units to provide homes for working-class families.

All of these efforts were integral parts of the New Deal and helped save millions of Americans from foreclosure, unemployment and homelessness. But they were also each, to varying extents, segregationist.

Until civil rights activists brought the Federal Housing Administration to heel during Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, the government agency refused to insure in black neighborhoods and worked relentlessly to enforce segregation in America’s rapidly growing suburbs. The FHA operated with such blatant racism that, in 1955, one of the nation’s leading housing experts wrote that its policies “could have been culled from the Nuremberg laws.”

But while the FHA’s influence endures in today’s hypersegregated metropolitan regions, the most infamous maps created during the New Deal’s dabble into residential real estate came from HOLC. These “Residential Security Maps” graded neighborhoods on their perceived investment risk and creditworthiness. Areas deemed to carry the least risk of mortgage default got graded “A” and colored green, while those neighborhoods considered “hazardous” and high-risk got a D grade and red shading.

The HOLC maps are where the term “redlining” originated. They represent some of the starkest visual images of 20th-century housing discrimination.

Operating on the principle that older neighborhoods could not be restored and were inevitably trending downward, many historic urban neighborhoods were rated D by HOLC. But it wasn’t only the age and condition of an area’s buildings and infrastructure that determined its rating.

The agency hired armies of local real estate agents to appraise the properties and neighborhoods, many of whom had already done racist mapping projects for the private sector and brought the same biases into their new government gig. The appraisers hired to conduct the mapping often employed discriminatory judgments against African-American neighborhoods. (One HOLC map in Richmond, Virginia, contained a scribbled appraiser’s note that a neighborhood’s weathered building stock was “Bad for whites; Fair for darkies.”) These resulting maps largely reflected earlier documents used by the real estate industry.

Areas populated by African-Americans were inevitably considered high-risk and rated D. Recently immigrated European groups, like Jews and Italians, warranted lower grades too.

In Philadelphia, many D-rated areas remain wanting for investment. Segregation remains endemic, if unofficial. In 2015, 41.6 percent of people in Peay’s North Philadelphia neighborhood were living below the poverty line, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Two-thirds of the population identified as black.

Yet some of today’s trendiest neighborhoods like Fishtown, Manayunk and all of South Philadelphia were redlined as well, despite having small brown and black populations (if any) in the 1930s. Instead these areas were rated D because of their dense rowhouse nature, their mix of recently arrived European ethnics, and the factories that were interlaced with residential building stock. Appraisers colored tony Rittenhouse Square yellow, rating it as declining, while more suburban areas of the city, sections like West Oak Lane, earned the highest ratings and have since weathered white flight and economic destabilization. Society Hill is today one of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods but on the HOLC map it is red. The urban renewal movement that would come after World War II hadn’t yet transformed the area into a stronghold custom made for well-to-do urban dwellers.

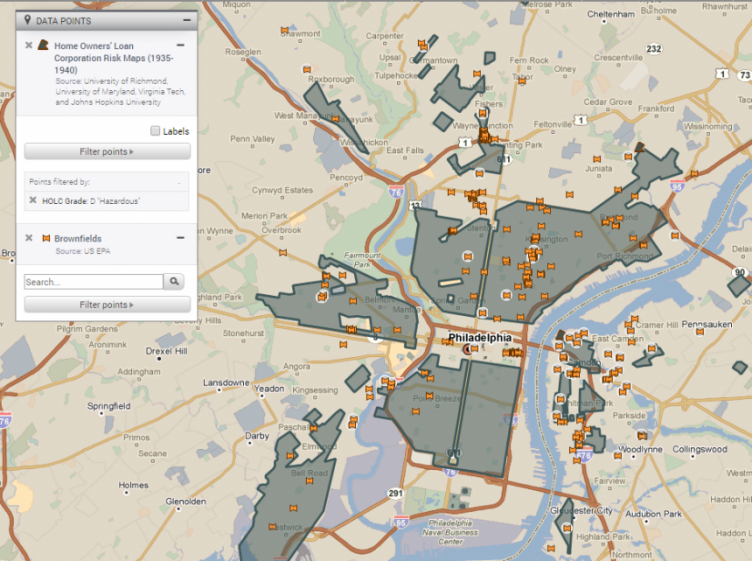

(Map by Azavea/Next City)

Recent scholarship by the University of Pennsylvania’s Amy Hillier calls into question how responsible HOLC itself was for the devastation that followed. It’s unknown how many other public or private sector entities used the agency’s maps. And HOLC itself still made plenty of loans in D-rated areas, despite the harsh judgments of their appraisers. In Philadelphia, Hillier found, the agency made 60 percent of its loans in the areas shaded red.

“To call them redlining maps implies that they caused the redlining, when in some ways they reflected practices already underway,” says Hillier, who’s a professor of social policy. “Those areas colored red and considered hazardous had already experienced disinvestment, and it was hard to get mortgages there.”

But, Hillier adds, her argument isn’t intended to dispute the overall narrative about redlining. “The arc of the story is definitely still true: Systemic disinvestment between the federal government, private sector and individual citizens caused long-term damage, in particular to urban neighborhoods of color,” says Hillier. “I think my version of the narrative — that private sector, academics and multiple federal agencies were all working together and buying into the same racist view of neighborhood change and ‘good’ investment — is even more insidious.”

Even if the HOLC maps are not the smoking gun they were once assumed to be, they do reflect the patterns of real estate discrimination that existed as the FHA began its stint as one of the most influential federal agencies of the 20th century.

And because the maps highlight areas that real estate industry players and the FHA strived to avoid, they still today show how undesirable development tends to crop up in neighborhoods inhabited by people of color. Take pollution-generating industrial and waste sites. A contemporary map of toxic brownfield sites overlays with the HOLC to show that a majority sit within D-rated areas.

Or consider public housing, which began as a segregated service with different complexes designated for white and black workers. But by the 1950s, public housing became mostly populated by black Philadelphians, and so the location of the sites almost perfectly correlates with the areas of the city that HOLC rated D and colored red. Of the over 60 public housing sites in Philadelphia mostly built by the government in the years between the issuance of HOLC maps and 1967, only six rose outside the D-rated sections of the city. In the entire 51 square miles of Northeast Philadelphia, largely developed after World War II and overwhelmingly white until the 1990s, there is only one small neighborhood that was given a D rating. It is this exact tiny area where the Northeast’s only public housing complex lies.

But if there is only correlation, and not causation, between the HOLC maps and Philadelphia’s hypersegregation, there is no such ambiguity about the role of the era’s other major housing agency. The Federal Housing Administration was profoundly biased against neighborhoods like the sections of the city graded D in the HOLC maps, areas like Peay’s North Philadelphia.

How the Federal Housing Administration (really,really) segregated Philadelphia, and America

Although comprehensive FHA maps do not survive in the way that HOLC’s do, the agency did leave other materials behind. In its 1939 “Underwriting Manual,” appraisers are warned that neighborhood property values are reliant upon consistency in “social and racial occupancy.” A particularly helpful way to conduct healthier lending, the book notes, is to insure white neighborhoods that are separated from black or mixed-race areas by physical impediments like waterways or railroad tracks.

“Natural or antically established barriers will prove effective in protecting a neighborhood … from adverse influences,” reads the manual. These barriers aid in “the prevention of the infiltration of … lower class occupancy and inharmonious racial groups.”

The monumental power of the FHA is hard to exaggerate. The FHA’s policies set the standard for mortgage lending in America. When the nascent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) started insuring mortgages for those returning from World War II, it simply adopted the FHA’s preexisting model. By 1950, half of all new mortgages in America were insured by the two federal agencies.

The agency’s racism ran deep. In 1938, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People got a tip from a sympathetic FHA employee that, “Unofficially, the FHA is making as one of its requirements for guaranteeing mortgages that the builders insert … [a] deed … clause prohibiting sale, rental, or occupancy by persons of African descent.”

A drumbeat of negative stories about the agency’s practices appeared in the black press, but the FHA did not fundamentally change its practices until forced by a 1968 act of Congress. Until then, they could be devastatingly petty in the enforcement of their discriminatory standards. Richard Rothstein’s book “The Color of Law” recounts a story from 1958 in which a white school teacher got an FHA-backed mortgage but couldn’t move in immediately. In the interim, he rented the house to an African-American friend. The FBI ended up investigating how the tenant managed to live in an all-white neighborhood, and the FHA blacklisted the white buyer from ever again obtaining a government-backed mortgage.

To Peay, in North Philadelphia, the inability of many African-Americans to obtain mortgages in the mid-20th century still hampers the community today.

“It was hard for black residents to buy houses in this neighborhood because all the lenders were redlining,” says Peay. “That affects the equity wealth and property ownership of black Philadelphians today. If your parents and your grandparents never owned a house, well, there’s a huge lack of ownership to this day because in history we didn’t get access to it.”

Black neighborhoods like the part of North Philadelphia where Peay lives weren’t the only ones slighted by the FHA. Racially mixed neighborhoods, or even just white neighborhoods adjacent to black populations were considered a bad risk.

The FHA’s bias also ran against urban areas in general. The 1939 underwriting manual warned against “crowded neighborhoods,” smoky environments and even single-family houses that could be used as a commercial property. Instead the agency preferred detached, single-family homes separated from commercial or industrial buildings. During the 1950s, in comparison to multifamily dwellings, they insured these kind of classic suburban homes at a rate of seven to one.

But there wasn’t an equivalency between the housing discrimination visited upon urban white communities and black city neighborhoods. White residents had an out: the suburbs.

Whitelining in the suburbs

“Redlining is just a small part of a much bigger story of segregation in urban areas like Philadelphia,” says Rothstein. “Levittown isn’t on a HOLC map. The biggest effect of these midcentury government policies was to give white families single-family homes with low-cost mortgages in suburban neighborhoods. [The FHA and VA] gave them an investment with value that appreciated for the next three or four decades.”

Rothstein argues that the FHA’s greatest contribution to the hypersegregation that defines American metropolitan areas today is the agency’s guaranteeing of massive loans to suburban developers like William Levitt. The plans and designs for the famed Long Island development, and its sister in the Philadelphia suburb of Bucks County, had to be submitted to the FHA for approval so he could then secure low-interest bank loans. One of the necessities for FHA approval was that Levitt and the dozens of other suburban developers like him, agree to not sell their new homes to African-Americans. Today, Pennsylvania’s Levittown is still overwhelmingly white.

“A government offering such bounty to builders and lenders could have required compliance with a nondiscrimination policy,” wrote Charles Abrams, in his 1955 book “Forbidden Neighbors.” “Instead, the FHA adopted a racial policy that could well have been culled from the Nuremberg laws. From its inception FHA set itself up as the protector of the all white neighborhood.”

Government-sponsored suburban developments like Levittown explain a big part of why public housing ended up being mostly African-American. The housing prices were so low in the FHA-insured suburbs that the monthly mortgage payments were often less than the rent in public housing, especially if a white family received veterans’ benefits.

The impact of redlining in today’s cities

The discriminatory practices of the FHA were outlawed in the last great civil rights law of the 1960s, the Fair Housing Act of 1968. But by then it was too late. The federal government’s appetite for investing in urban housing would soon radically diminish. (HOLC had been disbanded in the early 1950s, and nothing like it would be created during the Great Recession, while Richard Nixon would soon end the construction of new public housing units.)

By that time many of the industrial jobs that had drawn black Southerners to Philadelphia had vanished, especially from areas like North Philadelphia.

“They kept a lot of black residents from buying houses outside black neighborhoods,” Peay says. “That’s the other part of housing discrimination. A lot of the jobs around that time moved out, and it was hard for us to get those jobs outside the city because we couldn’t get housing outside the city. With no jobs, there’s no money. That means crime increases, drug abuse, all that.”

Residents of areas like North Philadelphia were trapped. Housing stock had deteriorated because loans for home repair or home purchase were so hard to come by. That led to a predatory rental market, where rents were jacked up for those who struggled to move elsewhere. Small business corridors fell apart for similar reasons, and because of the conflagrations of the 1960s and the movement of upwardly mobile African-Americans into new parts of the city and surrounding suburbs.

Predatory alternative mortgage products targeted the old redlined areas and newer African-American neighborhoods as well. Those who wanted to purchase homes had to go beyond the bounds of FHA-secured mortgages, and utilized more treacherous financial products. Even as the African-American population moved into surrounding white neighborhoods and beyond the areas delineated by the old HOLC maps, speculators and other housing predators followed them across West Philadelphia and north into Nicetown, Olney and West Oak Lane. Whites subsequently fled. These newly segregated areas, and the old African-American neighborhoods of the mid-20th century, were heavily targeted by subprime lenders before the recent Great Recession.

For all of these reasons and more, areas like North Philadelphia have languished, sprouting blighted properties and weedy lots. Conditions spawned of federally sponsored segregation breed fresh evils, and make it hard to attract new investment and new residents. Even heroin-wracked Kensington is experiencing more development than much of North Philadelphia, despite the latter area’s closer geographic proximity to transit and the jobs of Center City.

The city of Philadelphia has tried to help where it can. Recent efforts include the city’s land bank, created in 2013 to try and take control of the tens of thousands of vacant buildings and lots that have proliferated in the most divested corners of the city. This year, City Council is beginning to steer $100 million toward the Basic Systems Repair Program, which is meant to help low-income people fix their homes, and a loan program designed to offer a safe alternative to populations that cannot access traditional lending. An inclusionary zoning effort, promoted as a means to create mixed-income housing, is underway as well. But the city’s ability to reverse these trends is extremely limited, given its resource constraints and the long retreat of the federal government from urban affairs.

For Peay, at least, North Philadelphia’s problems can begin to be addressed if more people know about them and how things got to be so hard.

“Redlining and all that is an issue that no one knows about now,” says Peay. “It’s good we’re talking about this.”

—

This article originally appeared on Next City as part of the Philadelphia in Flux series supported by the William Penn Foundation.

Join Next City, Little Giant and WHYY for a free public discussion of redlining in Philadelphia on Saturday, Dec. 9 at WHYY. The panel discussion is part of Next City’s Philadelphia in Flux series and the launch event of Little Giant’s A Dream Deferred project.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.