At Millersville University, students are clamoring for cadavers

Biology students fearful that climbing costs could end cadaver studies have mobilized to support the program. But administrators say the activism is unnecessary.

Listen 2:02

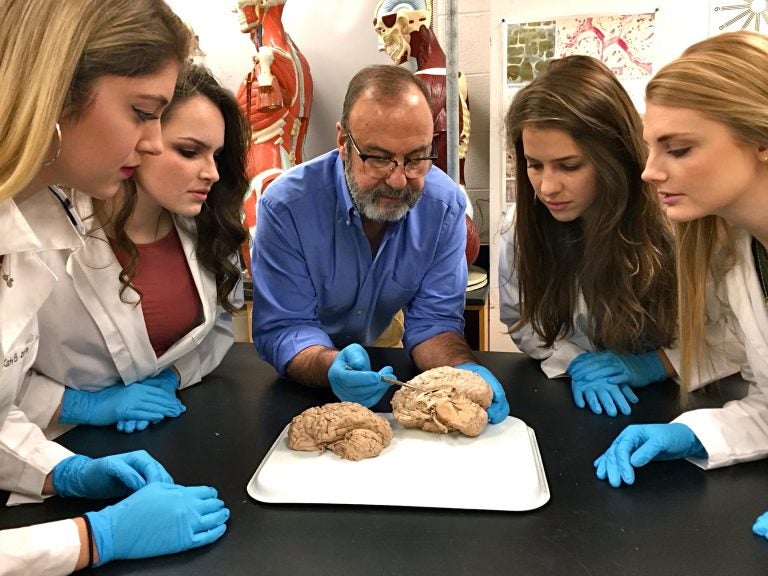

Biology professor James Cosentino (center) examines a brain at Millersville University with students (from left) Katy Good, Lexi Colgan, Clara Forney, and Jessica Hanner. (Photo provided by James Cosentino)

At other colleges, students protest everything from mascots and class times to cafeteria food and the closure of beloved bars.

At Millersville University near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, they’re mobilizing to keep their cadavers.

Four students in biology professor James Cosentino’s anatomy and physiology classes have collected more than 600 signatures on an online petition and plan to present a letter to administrators to save the cadaver program, which they fear may end when Cosentino, the professor who procures the bodies for Millersville, retires this month.

“Without the continuation of the cadaver program, this important aspect of learning retires with Dr. Cosentino,” students Katy Good, Jessica Hanner, Lexi Colgan and Clara Forney wrote in the letter. “The ability to study cadavers at the undergraduate level is rare and something that our university should be justly proud to promote.”

Cosentino, who is retiring after 30 years at Millersville, said his department’s budget for cadavers has stagnated at $2,000 a year for the past 20 years while their cost has quadrupled. That pricetag covers such expenses as embalming, shipping, storage, and cremation.

The petition and letter are the students’ first steps: They say they’re prepared to crowdfund to ensure they and future students can continue studying cadavers — and they even have a hashtag in mind for social media: #OverMyDeadBody

“This is something that’s necessary and needs to be funded,” said Colgan, 19, a chemistry major from West Grove, Chester County.

But administrators say there’s no need for anyone to lose their heads just yet.

“The cadaver program will continue. That was never in question,” university spokeswoman Janet Kacskos said.

Current funding will continue, and a new endowment should ease budgetary concerns, agreed Mike Jackson, dean of Millersville’s College of Science and Technology.

Dr. Joseph Choi, a 1996 Millersville graduate who now works as an orthopedic surgeon in north-central Pennsylvania, recently donated money to create The Choi Family Biology Endowment for Anatomic Studies at Millersville. The endowment is so new that even Cosentino, who gets the cadavers for Millersville, wasn’t aware of it. Jackson and Kacskos declined to divulge how much money is in the endowment, except to say at least $25,000 is required to create one.

Still, Jackson said he appreciated the students’ advocacy.

“We have no intention of getting rid of things that help our students be competitive and successful once they leave Millersville, and this is one of those,” Jackson said. “It is nice that they’re that vested and interested in their education. It’s always a very good thing to see that they enjoy the experience, and that they want to see it continue for future students.”

Cadaver study rare for undergrads

While it might seem unusual that cadavers would incite students to activism, the program’s appeal lies, in part, in its rarity. Besides Millersville, just a handful of undergraduate schools statewide — Salus University, Messiah College, Lycoming College, and St. Francis University among them — have cadaver labs.

“It puts us steps ahead, already knowing things that graduate students don’t know going in to their degrees,” Colgan said.

Physiology professor John E. Hoover, who chairs Millersville’s biology department, agreed: “It’s not a very common experience for undergraduates to have an opportunity to study anatomy with the use of real cadavers. More and more universities are going to software programs and things like that.”

Pennsylvania’s nine medical schools have cadaver programs, but, even there, cadavers are in short supply, according to Clariza Murray of the Humanity Gifts Registry.

The state created the nonprofit registry in 1883, when there was no legal way for medical schools to obtain bodies for scientific study. Now, it distributes about 700 cadavers a year to Pennsylvania’s medical schools. That’s about 200 fewer than needed, Murray said.

“We can’t meet our need,” she said, especially considering how for-profit cadaver companies such as LifeQuest Anatomical and Science Care have lured away donors with promises of no-cost donation and free cremation.

Learning about biology, life

Cosentino and Murray agree that cadaver labs are worth the expense, because bodies offer lessons students can’t get from textbooks alone.

“The cadaver program has been very, very popular here,” Cosentino said. “Looking at these structures in three dimensions and true size is so much more valuable than looking at charts, and there’s quite a bit of difference in different animals.”

He added: “There’s all kinds of different things we can see. People who want to be physical therapists are going to be able to see the muscles and how they attach and interact; they’ll also be able to see the nerves that are enervating the different muscles.

“For students going into respiratory therapy, we can take a look at the thoracic cavity. I’d say 25 percent or so of the cadavers I’ve gotten have died from smoking-related illnesses, and they can see the effects of smoking on the lungs quite directly.

“If a patient has died of heart attack, we can see the damage to the heart. We often get patients who have died of leukemia, and they can see the accumulation of white blood cells throughout the body. We often get cadavers that have some sort of prosthesis. One had an artificial knee, so students got to see how the artificial knee was fitting in. Others have had pacemakers.”

Cadavers offer less tangible lessons too.

“You definitely can’t be squeamish every time you’re in an [operating room],” said Hanner, 22, a biology student from Lancaster. “Aside from being able to see all the different muscles and organs and things, a key aspect of keeping the program (is learning if you are) able to desensitize yourself and seeing: Does this make me squeamish? Is this the right career choice for me? Am I going to be able to step in an OR and do what I need to do and not have any other emotions attached to it?”

Millersville used to have four cadavers at any given time for students to study, but had to reduce that to two, as costs have climbed, Cosentino said. The biology department keeps each cadaver for up to two years for dissection and examination before returning cremains to the donors’ families, he added.

Cosentino applauded his students’ effort to save the cadavers, even if they don’t need saving. Student activism is every bit as instructive to life success, he said, as cadavers are to scientific study.

“I went to college in the ‘60s, and we would do things like, in order to get rid of the ROTC requirement, we would take over the administration building. We haven’t seen that kind of activity amongst students since then,” Cosentino said. “But I’m starting to see that more and more as students are getting very much involved in politics and things that are going to change their world around them. This is a whole different generation, just in the past 10 years. I’m very optimistic.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.