Does a mom’s stress affect her offspring for generations?

Researchers are studying the factors that can make epigenetic changes to DNA. A mom's stress, diet and daily habits may become an inheritance of sorts for her kids.

Listen 15:33

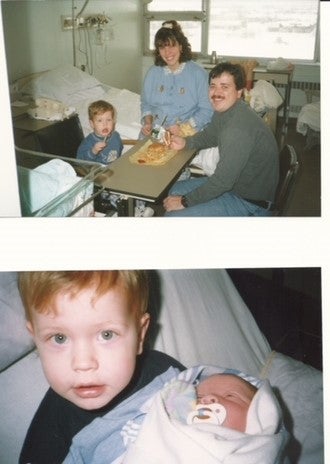

Vincent Turcotte and Valérie Hayes are both ice storm babies, born shortly after a massive storm debilitated their city. Scientists are trying to figure out if the stress their mothers experienced during the natural disaster has helped shape who they are as people. (Courtesy of Julie Groleau.)

In early January, 1998, a massive ice storm blanketed the areas around Ottawa and Montreal in Canada. Thick ice encased trees, roads and utility lines and shuttered gas stations, grocery stores and other basic services. Power failed.

“It was like a war zone … There was nobody in the street,” said Julie Groleau. “It was pretty scary.”

And stressful.

At the time, Groleau was eight months pregnant. She hunkered down with stranded friends in her little house in Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu, a city southeast of Montreal.

Her home had a fireplace for heat, so they took turns staying up to tend the fire and cooked canned spaghetti on the wood stove. This went on for a couple of weeks.

“I was telling my baby, ‘Don’t come out now, don’t come out now. Stay in. You’re better in than out.’”

She started delivering on January 22. And, while she was laboring at the hospital, there were intermittent blackouts because that facility was relying on generator power.

She welcomed her son Vincent without problems, though, and soon after the power in her home returned.

But, when Vincent started having allergies and other health issues, Groleau wondered if his health problems had anything to do with the stress she experienced during the storm.

In Montreal, Suzanne King, a psychiatry professor at McGill University, was asking similar questions.

She launched a study looking into whether the storm would affect children born to mothers who were pregnant during the weather event. Her team wanted to understand which aspects of the mom’s stress would affect the child and in what ways: cognitive development, motor development, physical or behavioral development.

The storm was a good opportunity for studying the repercussions of stress in pregnant women because it was an independent event; it could be isolated from other everyday stressors, like work or money problems.

Groleau signed up.

King and her team have been following Groleau and nearly 200 other mother-child pairs for two decades. They’ve also launched similar studies after other natural disasters: a flood in Iowa, another in Australia, a fire in Alberta. In each case, they’re asking slightly different questions.

Their finding: a mother’s stress does influence her child.

Researchers were surprised that different kinds of stress caused different outcomes. In the ice storm cohort, the mothers’ objective stress from the storm was the best predictor of the children’s cognitive development, like IQ and language. It also affected physiological development. For example, they found that ice storm kids are more likely to have obesity.

Subjective stress is linked to behavioral outcomes. King says the ice storm kids’ levels of anxiety and depression are increasing as a group to above average for children their age. And as these now young people grow older, they’re also becoming more anxious and more passive.

The researchers believe these trends are due to epigenetic changes.

Basic genetic changes in a person usually mean changes to the sequence of their DNA. Epigenetics is how traits can change without altering the actual sequence. Instead, shifts occur when genes receive signals that activate or deactivate them. Researchers think the signals may be the body’s way of programming the developing child for the world they’re emerging into — to prepare them. But stress could send the wrong signals, resulting in a mismatch when the child is born. And some studies suggest that mismatch could be passed down to future generations.

Julie Groleau’s son, Vincent, still suffers from serious allergies. As a 20-year old he’s very quiet and low-key — he could fit some of the characterizations of the ice storm babies. One can’t really connect these traits to any particular child and say the storm caused them, but Groleau, his mom, still wonders about that.

Meanwhile, researcher Suzanne King is looking for ways to stop stress from sending improper signals to developing babies. Since August 2017, when Hurricane Harvey devastated Houston, King and her partners in Texas have been recruiting women who were pregnant during or right after the storm. The scientists want to test a writing intervention.

Johanna Bick, a University of Houston researcher working with King, said they’re testing whether a writing exercise could reduce stress in participating women and protect their babies.

“If we can establish that this is effective then this would be really valuable for future events like Hurricane Harvey that we know are going to occur,” Bick said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.