Bill seeks to streamline faster wireless broadband, steamroll local control of the streetscape

Opponents, however, fear the bill will simply preempt local control of an inherently local issue.

Listen 3:44

One of Doylestown's decorative street lamps near the intersection of Main and State streets. (Google Maps)

Jack O’Brien was explaining how Doylestown got into this legal mess when the call cut out.

There was some static, some garble, and then the connection strengthened a bit. “That’s the other part of this,” the president of Doylestown’s Borough Council said, “there [unintelligible] coverage spots in town.”

Just what, exactly, O’Brien was trying there to say wasn’t clear, much like a lot of the cellphone calls in this small town, but the gist was this: Doylestown could do with better wireless coverage. Yet its objections to how one company intended to upgrade mobile broadband infrastructure in the area was why he was calling in the first place.

O’Brien made this cellphone call while on his way to lunch with his wife at the Bagel Barrel — “I grew up in New York City, this is the closest to a New York bagel I’ve ever found,” he raved — on State Street, just a few blocks from Main Street, in the heart of Doylestown’s historic downtown. It’s a charming part of the Bucks County seat, where faux-historic street lamps no taller than a basketball hoop dot the sidewalks every few yards, accenting the neighborhood’s vintage chic. Even the utilitarian traffic lights are adorned with decorative capitals, the kind of attentive flourish that beguiles would-be residents into checking out local real estate listings.

So when wireless-network builder Crown Castle International Inc. wanted to attach a bunch of “small cell” wireless antennas to Doylestown’s street and traffic lights, the borough fought back, enacting a zoning ordinance that strictly regulated where and how such wireless infrastructure could be built.

“In the center of town here, we have historic light poles, they’re cast iron-looking and decorative, and we wanted to maintain the sense of that in the center of town,” said O’Brien. “They were proposing coming in and just putting wooden poles in, and [in] some cases they’d be 50 feet high and they just don’t fit with the nature of the town.”

Crown Castle sued the borough in both state and federal court. Eventually, the two sides settled, agreeing to allow most of the cellular infrastructure, but requiring that the company make the antennas and attached boxes less noticeable. Crown Castle also agreed to pay a small rent for the right to install its equipment on borough property.

It is precisely this kind of give-and-take, hard-fought negotiation that a bill working its way through Harrisburg now seeks to prevent. If it passes, supporters say, HB 2564 would provide “uniformity” to how the commonwealth’s 2,562 municipalities review and approve applications to build next-generation wireless infrastructure. Opponents, however, fear the bill will simply preempt local control of an inherently local issue: what can and cannot be put on a town’s utility poles, streetlights, and traffic signals.

It’s a legislative fight that pits the theory of small-town accountability against the competitive mandates of the free market, and threatens to mar historic streetscapes in the name of technological advancement.

HOW YOU’RE READING THIS ON YOUR PHONE (IF YOU’RE READING THIS ON YOUR PHONE)

In little more than a decade’s time, smartphones have become ubiquitous. According to Pew Charitable Trusts, 77 percent of Americans own smartphones. Increasingly, those without broadband access at home rely on their smartphones to access the internet. When they do, they either log on to a local Wi-Fi router or rely on the area’s wireless network.

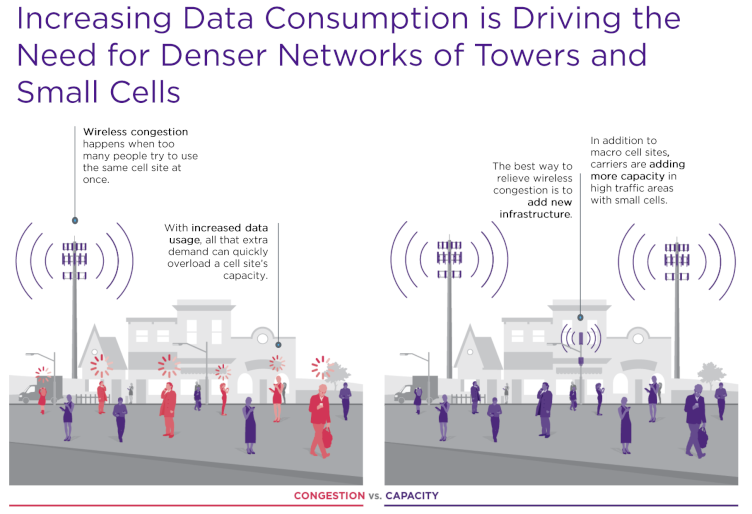

All those cellphones doing increasingly data-hungry things — like movie streaming and live video chats — tax the existing cellular networks, which largely rely on a web of 150,000 antenna towers spread across the country, each covering a range of a few circumferential miles.

Those towers are more densely packed in more densely populated areas, though, to provide enough service for the greater number of users. And as wireless carriers ramp up for the next iteration of cellular technology — 5G, a step up from the current high-end of 4G LTE — the demand for even more mobile antennas in even more tightly packed clusters will grow.

The incipient rise of America’s 5G network is being built on the back of “small cell” infrastructure — cellular antennas that are smaller both in size and in coverage area than the massive towers that mostly provide wireless connections today. Small-cell antennas are roughly five feet tall and connect to boxes roughly the size of a small refrigerator.

While cell towers have a range of a mile or two, these small cells cover only a block or two — or even less, depending on how much collective cellphone data you might want to provide. They’re already popping up in cities like Philadelphia to clear up congestion on 4G LTE networks: A few strategically placed small cells are why you can post a video of a Phillies home run to Instagram without leaving the nosebleed section of Citizens Bank Park.

According to Colby Synesael, an equity-research analyst with the investment firm Cowen, about 70,000 small cells were built across the United States last year. Over the next five years, Synesael estimated, the wireless industry will build another 200,000.

The next generation of smartphones, set to hit the market starting in 2019, will be built for 5G — meaning download speeds three to four times faster than the usual 4G LTE connection today, and with a fraction of the latency, or lag, between devices.

It’s 5G that finally will unlock the future imagined for us by “The Jetsons” and Epcot, backers say. Everything from the Internet of Things, to autonomous vehicles, to uses we can scarcely imagine will be made possible by the magic of faster downloads and reduced lag — or, at the very least, you’ll be able to stream movies on your phone with ease.

Just as the four major wireless carriers — Verizon, Sprint, AT&T, and T-Mobile — courted customers with the size and robustness of their 4G and then 4G LTE networks, soon they’ll fight for bragging rights to the biggest and best 5G networks. And it’s companies like Crown Castle that will help them get there — leasing spaces to install small cells, then subleasing the infrastructure out to the carriers. Currently, Crown Castle is the largest player in this field, but it’s far from the only one. Competition is fierce.

“5G is coming to every community in America,” said Rory Whelan, regional director of government relations at Crown Castle. “The question is: Who is at the front of the line, who is at the back of the line?”

KEEPING PACE IN THE 5G RACE

Without a law streamlining the regulatory approval process statewide, Whelan said, Pennsylvania risks winding up closer to the back of the line. Just how long a wait that will mean, Whelan can’t say. But Synesael, the analyst, noted that the future of 5G in Pennsylvania isn’t exactly hanging by this legislative thread.

“It’s not black and white,” Synesael said. “Even if the bill is denied, I wouldn’t expect Crown Castle to completely ignore the Philadelphia marketplace. It’s just the magnitude of investment which they make will most likely be something less.”

Crown Castle and its competitors will, to a certain extent, chase the easier investments — the towns and states that have laid out the red carpet. Twenty states have passed versions of the uniformity bill backed by the Pennsylvania Partnership for 5G, an industry lobbying group formed by Crown Castle, among others.

But regardless of the statutory landscape, Pennsylvanians will start seeing small cells popping up in more populated areas. Indeed, they already are. The wireless carriers that contract with companies like Crown Castle are chasing smartphone users, after all, which means they’re looking to expand their networks first in places where cellular networks are already running into bandwidth-traffic snarls.

“Absolutely, that’s where the carriers go,” said Crown Castle’s Whelan. “They go where the people are, meaning the demand and capacity warrants the building out of the network, and then we go where they ask us to go.”

The corollary to this is that rural areas will continue to lag in cell coverage, legislation or no legislation.

The bill’s sponsor, State Rep. Frank Farry (R-Bucks), said the bill will help prevent some areas — like Doylestown — from holding out and slowing the advance of 5G for their neighbors.

“Are [wireless infrastructure companies] going to roll out [5G]? They sure are,” Farry said. “Is it going to be delayed? Absolutely. Will there be as many municipalities completed here in Pennsylvania? No. I’m sure there won’t, because it’ll be a more expensive process.”

Roderick Hills, a professor at New York University who studies land-use law and preemption, thought that was overstating the problem.

“It’s a little bit silly to say that the cost of going through the local zoning process is so exorbitant that the telecommunications system would be ruined if one had to undergo local approvals,” said Hills.

“Cellphone towers are a regionally necessary LULU — a locally undesirable land use,” Hills explained. “Everybody needs cellphone towers, but no one wants them right next door — they want them in the next neighborhood over, that way they get all the benefits of the LULU but none of the worries about health risk or the aesthetic worries.”

“But of course,” he continued, “if every neighborhood fought LULUs successfully, then every neighborhood would be frustrated in the desire to get cell service. So, some people say, ‘Look there’s a collective action problem if local zoning authorities have control over regionally necessary LULUs.’ ”

The bill would curtail local government’s ability to regulate the placement of small-cell infrastructure along public rights-of-way such as streets. It would effectively treat companies like Crown Castle as utilities — something Commonwealth Court recently ruled they are, reversing the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission’s ruling that they were not — thus allowing them more leeway to do what they want in public spaces than other, non-utility companies are permitted.

“We just don’t think that the local government rights of zoning and right-of-way management need to be preempted in order to do this,” said Rick Schuettler, executive director of the Pennsylvania Municipal League.

Crown Castle’s Whelan took exception to that characterization of the bill. “I don’t think it’s an accurate description to say that this usurps local control,” he said. “It does afford a more uniform approach going forward.”

Other than citing regulations that apply evenly to everyone — like traffic safety rules that forbid blocking an intersection’s sight lines with bulky cellular equipment — cities would be hard-pressed to deny permits to install small cells on existing city infrastructure if there were room for it. The bill also would give companies the right to build new utility poles if they saw fit.

Schuettler said his group is open to compromise — they’re not knee-jerk obstructionists or Luddites opposing technological advances just for the sake of it. If the bill could be amended to allow localities more control over areas like historic districts and neighborhoods that run all their utilities underground, they’d be open to supporting it. The fees — currently just $25 per year per small cell — and the regulatory processing time limits — just 15 days to process an application — also need to increase, Schuettler said. But his group is not philosophically opposed to the idea of surrendering a bit of local control over the streetscape to speed along technological advancement.

If it does pass, the bill would not disrupt existing agreements like Doylestown’s. Still, that doesn’t make O’Brien feel much better about the proposal.

“I really think taking that kind of control or opportunity away from the local municipalities is a mistake,” he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.