5 lessons one doctor learned from the times he almost died

How five near-death experiences drove David Fajgenbaum to live his life to the fullest, and discover a novel treatment for Castleman's disease.

Listen 18:16

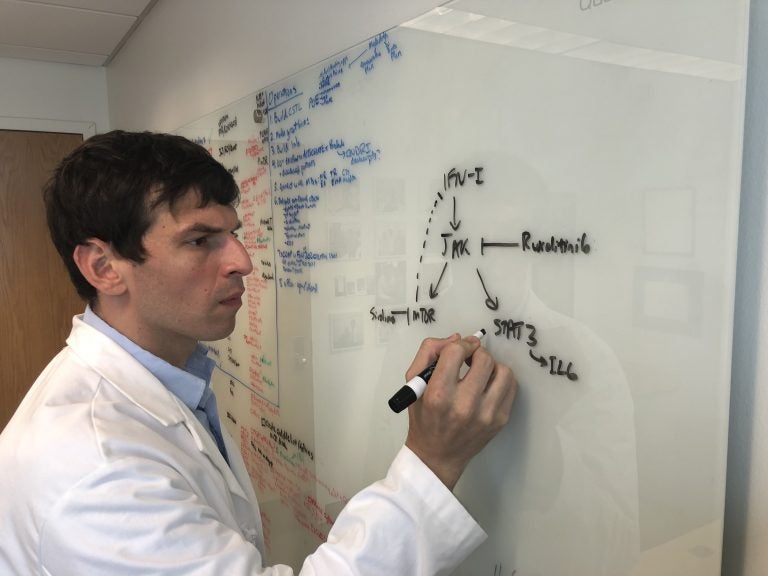

David Fajgenbaum leads a research lab at the University of Pennsylvania dedicated to studying Castleman disease, a rare illness that nearly killed him five times. He has recently shifted his focus to look at ways of treating COVID-19. (Courtesy of David Fajgenbaum)

David Fajgenbaum was 25 years old the first time he almost died.

He was in his third year of medical school at the University of Pennsylvania. His goal was to become an oncologist — an ambition born several years before, after watching his mother die from brain cancer.

In the summer of 2010, he was closer than ever before.

“I was done with my book work and now finally treating patients in the hospital,” he said. “I was loving it, and I felt like I was finally achieving the things that I had been setting out to achieve and becoming a physician.”

And then, out of nowhere, came the symptoms — abdominal pain, lumps in his neck, fluid in his legs. But worse than anything was the insatiable fatigue, which eventually forced him to take micro-naps between each patient.

Finally, after struggling his way through an exam, Fajgenbaum went to the emergency department.

“And that’s when they did blood work and they informed me that my liver, my kidneys and my bone marrow were all shutting down,” he said. “I was hospitalized right away.”

That was the beginning of a 3 ½-year saga, during which Fajgenbaum — a former football player whom his friends had nicknamed “The Beast” — would descend into an illness so great, so resistant to treatment, that it brought him to the brink of death no fewer than five times.

Eventually, Fajgenbaum was diagnosed with idiopathic Multicentric Castleman disease — a rare illness that, at that time, had an expected survival rate of just a couple years.

“I thought a lot about my mom,” he said. “I thought a lot about what it was like when she got such a bad diagnosis with her brain cancer. And it was terrifying.”

Because it’s so rare, Castleman disease isn’t well understood. That was especially the case 10 years ago. Fajgenbaum describes it as a cross between cancer and an autoimmune disease.

“At its most basic sense, it’s just the immune system becoming hyper-activated and then attacking your vital organs for an unknown cause,” he said.

Fajgenbaum sought out the world’s leading expert on Castleman’s, and over the next couple of years, exhausted all known treatments for the disease.

He remembers the moment his doctor told him that the latest experimental drug wasn’t working — and that there were no more options left.

“Within just a couple of minutes, I went from being this really optimistic Penn med student who was fighting cancer and who just hoped and prayed that this drug would work, to realizing that this drug was not going to work for me and that I was out of options,” he said. “And that I would need to start fighting back and start to try to identify drugs and treatments that could maybe help me and other patients.”

So that’s exactly was Fajgenbaum did. In between his relapses, he launched the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network, a nonprofit aimed at coordinating and pushing ahead research on the illness.

He also started doing his own research — using himself as a subject. But before the projects could bear fruit, Fajgenbaum had another relapse, which attacked with terrifying speed.

“Everything failing, fluid everywhere, organs shutting down, difficult to breathe — just within days in the ICU,” he said.

It was his closest brush with death, and offered a frightening wakeup call.

“I was in denial — I was like, it can’t be a relapse,” he said. “I haven’t made enough progress yet. This can’t be it — I need more time.”

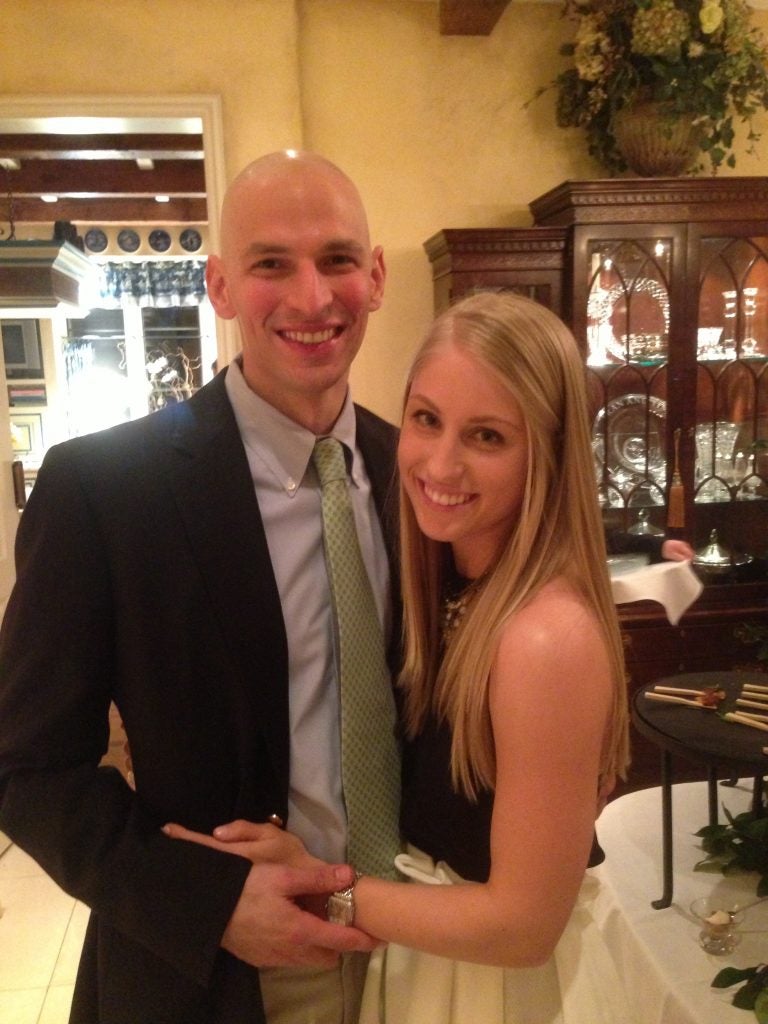

He needed more time to find a cure — but he also needed more time to live. By then, Fajgenbaum had become engaged, and was desperate to survive long enough to attend his own wedding.

“This is when I realized that I needed to study my Castleman disease,” he said. “If I was going to make any progress for Castleman disease, for other patients, for all these patients around the world, I needed to survive.”

So Fajgenbaum doubled down on his own personal research. He started poring through his own medical records, along with data from the experiments he’d done on his own samples.

“I knew I couldn’t develop a new drug,” he said. “That would take 10 years and $1 billion. But maybe I could find something in my data that would suggest that something was wrong, where there was a drug that already exists that could target that thing.”

After several weeks of intense work, Fajgenbaum found what he was looking for — signs that his immune system had started gearing up for a fight as much as five months before his latest relapse.

Fajgenbaum speculated that if he could block the specific communication line that triggered that activation, called the mTOR pathway, maybe he could stop his immune system from overreacting and causing a relapse.

As it turns out, there was already a drug out there that does exactly that, called sirolimus.

“This drug was dropped 30 years ago for kidney transplantation,” Fajgenbaum said. “It had never been used before for Castleman disease — but I was out of options, and so I decided to try it on myself as the first patient with Castleman’s.”

As of January 2020, Fajgenbaum has been in remission for about six years — though, even now, he counts his progress in months.

“Today, it’s now been almost 71 months — I think it’s like 71.92 months,” he said. “I can’t round up; I don’t know if I’m going to make it to 72 months. But I also won’t round down because we worked really, really hard for each portion of this remission.”

He runs his own lab at the University of Pennsylvania dedicated to Castleman research, and helps lead the Penn Orphan Disease Center, in addition to continuing with the organization he founded, the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network.

He said he spends most waking hours either working on a cure for Castleman — or with his wife, Caitlin, and their 15-month-old daughter, Amelia.

“The fact that I have this disease is what has me working as hard as I do during the day,” he said. “It’s what makes me spend so much time, as much as I can, with Caitlin and Amelia.”

He’s forever conscious of the fact that he could relapse at any moment — and that the drug that’s kept him in remission isn’t a cure for everyone. So far, research indicates that, like other Castleman treatments, it works for some patients, but not all.

That sense of urgency has transformed the way Fajgenbaum lives.

“It’s not just like, ‘We have a certain amount of time, we need to make the most of it,’” he said. “It’s that if we can make the most of it, the way that I think we can in the lab and through our research, then we can actually make more time for me and for a lot of other people. And so it’s kind of like a race against the clock.”

It’s a stressful way to live — but Fajgenbaum’s had good training.

“I nearly died five times over the course of a 3 ½-year period after my diagnosis,” he said. “And with each of those near-death experiences, I learned a lot about life and about living.”

Fajgenbaum recorded everything he experienced and learned in his recent memoir, “Chasing My Cure.” Here, he distills five of the lessons he gleaned — one for each time he almost died.

Lesson 1: Treat every moment like overtime

Fajgenbaum’s first big lesson arrived after weeks of illness, when he was so close to death that the hospital sent in a priest to deliver his last rites.

“I remember it being very dark,” he said. “I remember being pretty confused. But I remember seeing the priest and knowing somewhere in my brain what this meant.”

Through the haze of his illness, the priest’s visit flipped a switch in Fajgenbaum’s brain. He was supposed to be dead, and the fact that he wasn’t was a gift — a chance to squeeze just a little more life from whatever time he had left.

“I’ve kind of considered that moment to be the start of my overtime,” he said.

“If you think about the Eagles or any sports team, you can make a mistake in the first quarter, and you can make up for it. But in overtime, you can’t make a mistake. Every second truly has to count.

“And in overtime, there’s this profound sense of focus, where everything has to be so intentional and there can be no wasted movement, no wasted time.”

It’s a lesson, Fajgenbaum said, that everyone should take to heart.

“I can appreciate being in overtime because of how close I’ve come to death and because I can hear the clock ticking,” he said. “But I also appreciate and realize that we should all live like we’re in overtime.”

Lesson 2: ‘Think it, do it:’ Live without regrets

It was during another brush with death that Fajgenbaum had an epiphany: “I realized I didn’t regret anything that I had done or I had said. I only regretted the things that I had not done or had not said and would not be able to do.”

Specifically, at that moment, Fajgenbaum regretted losing his girlfriend, Caitlin. The two of them had broken up six months before, when work and school forced them to go long-distance.

“When we broke up, we both looked at one another and we said, ‘You know, if it’s meant to be, it’ll work out. We have all the time in the world,’” Fajgenbaum said. “And then, there I was, dying in a hospital bed, and realizing I didn’t have any more time.”

As soon as he was well enough, Fajgenbaum got in touch with Caitlin, and the two reunited.

The experience imprinted on Fajgenbaum the importance of action.

“I had this really profound sense that, moving forward — if I survived — I would not just think about things,” he said. “If I was thinking about it, I should do it.”

It led to one of Fajgenbaum’s life mottos: “Think it, do it.”

Lesson 3: Humor can be one of your greatest weapons

Around the time of Fajgenbaum’s third relapse, his father came to visit him in the hospital.

He was feeling better after high-dose chemotherapy, but looking the worse for wear. He was bald from the treatment, and had accumulated pounds of fluid around his middle because his liver and kidneys had stopped working.

But on that New Year’s Eve, he was feeling well enough for a walk around the hospital. On one of their laps, Fajgenbaum and his father encountered a drunk guy in the waiting room.

“He was kind of like swaying in his chair,” Fajgenbaum said.

On their next lap around, they found that the man had fallen to the floor.

“And so my dad ran over and helped him back into his chair,” Fajgenbaum said. “And he looked at my dad and I, and he said, ‘Thanks so much. Good luck to you and your wife.’ And I was like, `What is he talking about?’ And I looked at my belly, and I realized he thought I was my dad’s pregnant wife. And so I turned to my dad, I said, ‘Dad, you’ve got an ugly wife!’ And the two of us just burst into laughter.”

Only a few months before, Fajgenbaum said, he wouldn’t have been able to laugh at something like that. But the more he learned about his own resilience, the more important humor became.

“I think laughing in the face of death and disease is kind of the last thing that you think that you would want to do,” he said. “But actually, it kind of gave me like a sense of like, I don’t know if it was like power over the disease, that like, ‘Yes, disease. I know you’re awful. I know you’re killing me, and I know you’re making me get chemotherapy and you’re even making me look like a pregnant woman. But I’m going to laugh with my dad, and this is going to be something that we’ll never forget — that time when this guy thought that I was, you know, my dad’s pregnant wife.’ And even though the disease was clearly winning, it made me feel like I was like doing something to fight back.”

Lesson 4: How to save yourself: Turning hope into action

It took finding out that he was out of options that made Fajgenbaum decide to take matters into his own hands.

After finishing medical school, he attended the prestigious Wharton School of business at the University of Pennsylvania, and launched the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network — an organization designed to push forward the search for treatments.

He also started doing his own research, using himself as a subject.

For years, he’d put his trust in the medical powers that be. But desperation made him realize that if he wanted a cure, he might have to find it himself.

“The concept of turning hope into action is probably the thing that’s made the biggest impact on my life,” he said. “I was a very hopeful person before I became ill. I believed that there was kind of an order to things. I just felt like, if it was important, that it would be done by someone somewhere. But I’ve since learned that if it’s something that I’m hoping for, or something that I or someone else is praying for, that we should figure out ways to actually make that a reality.”

Lesson 5: Solutions hide in plain sight

With the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network, Fajgenbaum had put into motion a project that united researchers from around the world, and enlisted some of medicine’s finest minds to move the ball forward.

In general, developing new medications can take years and millions of dollars. But in the end, Fajgenbaum found his very own cure in a medication that’s stocked in pharmacies on every corner.

“With this fifth time I nearly died, I think the biggest lesson that I took from it is that solutions can sometimes be hiding in plain sight,” he said. “How many other drugs are there — out there? How many other solutions are there — out there for diseases and for other industries where they already exist? Just someone has to find it.”

You can read more about David Fajgenbaum’s journey and the five lessons he learned in his book: “Chasing My Cure: A Doctor’s Race to Turn Hope Into Action”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.