An unexpected item is blocking cities’ climate change prep: Obsolete rainfall records

Heavy rain from the remnants of Hurricane Ida flooded roads and expressways in New York in 2021. In a hotter climate, rainstorms are becoming more intense. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

American cities are poised to spend billions of dollars to improve their water systems under the federal infrastructure bill, the largest water investment in the nation’s history.

Those new sewers and storm drains will need to withstand rainfall that’s becoming more intense in a changing climate. But as cities make plans to tear up streets and pour cement, most have little to no information about how climate change will worsen future storms.

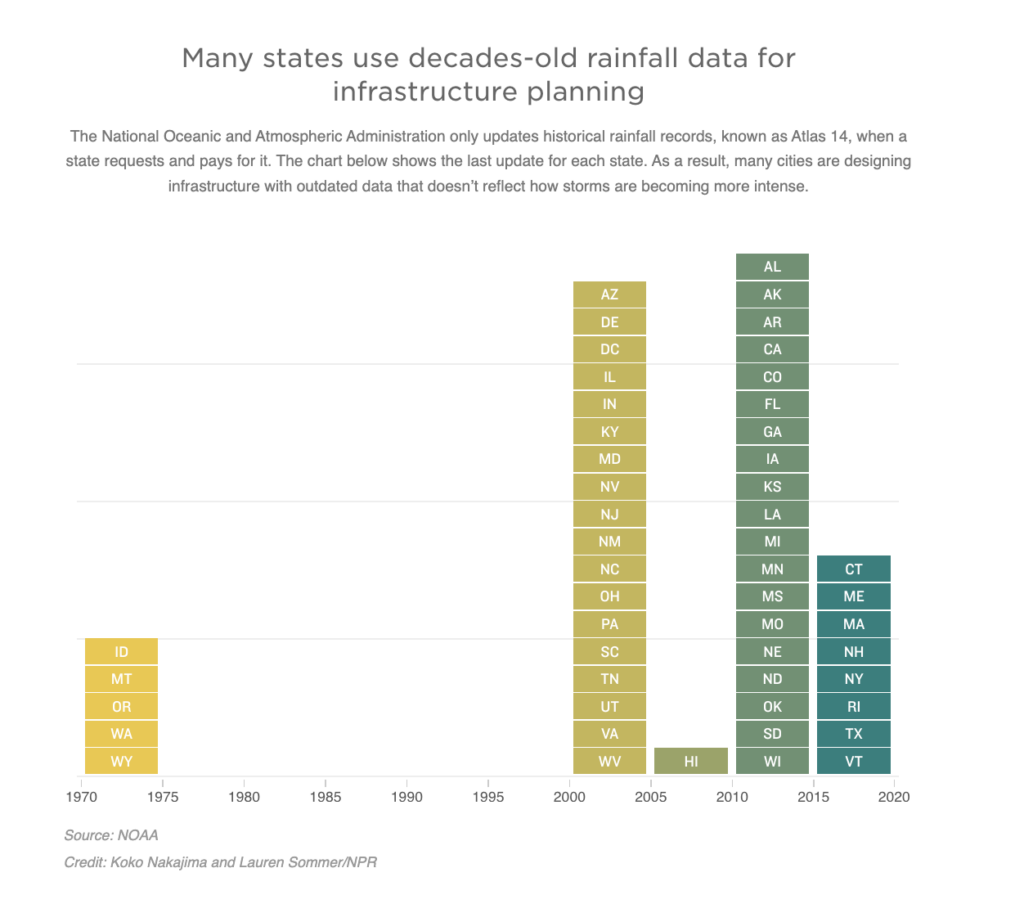

Many cities are still building their infrastructure for the climate of the past, using rainfall records that haven’t been updated in decades. Those federal precipitation reports, which analyze historical rainfall data to tell cities what kinds of storms to plan for, are only sporadically updated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Rainfall reports for some states are 50 years old, which means they don’t reflect how the climate has already changed in recent decades. And states themselves have to pay for those updates.

The disconnect between the kinds of upgrades a changing climate demands and the data available to communities is already imperiling lives. Heavier downpours are taking an increasing toll on cities, inundating homes and roads. Last summer, for example, fifty people drowned when the remnants of Hurricane Ida overwhelmed urban stormwater drainage systems in the Northeast.

Now, as NOAA determines how to spend its own infrastructure bill funding, many cities are hoping the agency commits to doing regular, nationwide updates of its precipitation reports, known as Atlas 14, to provide a systematic snapshot of how storms have already intensified.

Still, those up-to-date records won’t show how the climate will continue to change in the future. So many flood planners are also pushing NOAA to fund and release local forecasts of how rainfall is expected to intensify going forward, to ensure that infrastructure projects built today won’t become obsolete as temperatures warm.

“It’s core to probably hundreds or thousands of development decisions everyday,” says Chad Berginnis, executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers. “If we have over a trillion dollars going out the door in infrastructure, then let’s have the very best standards and data so we’re designing this stuff right.”

Infrastructure built for the climate of the past

When Hurricane Harvey hit Houston in the summer of 2017, the slow-moving storm dropped as much as 60 inches of rain. The destruction left in its wake cost $125 billion, with more than 100,000 homes damaged.

But even before the hurricane hit, city planners had begun to realize that storms, much weaker than Harvey, were becoming a greater danger because the infrastructure wasn’t designed for them.

In any city, the only thing stopping rainwater from flooding roads and homes is a lowly, unglamorous piece of infrastructure: the storm drain. In heavily paved areas, rain isn’t absorbed into the ground, and the run-off needs somewhere to go. Storm drains connect to miles of underground pipelines that carry runoff away.

The size of storm drains and pipes limits how much water the system can handle. When they’re overwhelmed, flooding can happen in neighborhoods far from any river or creek, where residents likely lack flood insurance.

Cities decide on the size of a stormwater system by using a particular kind of storm, known as a “design storm.” In some places, the stormwater infrastructure is designed for a storm that’s considered a 1-in-5 year storm, or that has a 20% chance of hitting. Other cities plan for an even more severe storm, like a 1-in-25 year storm.

To figure out how much rain those storms will unleash, many communities turn to the federal government. NOAA releases precipitation records through its Atlas 14 reports, which analyze the historical rainfall in a given region and then tell local planners how much rain is produced in both common and extreme storms.

But for many states, those records are outdated. Prior to Harvey, some local agencies in Texas were using NOAA records last released in 1961. Harris County, where Houston is located, analyzed rainfall data on its own, but the records were still two decades old.

Regional planners knew urban flooding was on the rise. Intersections and roadways were getting swamped with water in heavy rain. But to get new precipitation data that captures how storms have already changed in recent years, local or state agencies need to pay the federal government for it under NOAA’s policy. The agency itself has historically not had the budget to conduct the studies. A group of local flood agencies in Texas, along with the regional office of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, raised $1.75 million for a statewide study in 2016.

The results confirmed what they suspected: rainstorms have already gotten more intense.

The NOAA analysis found that a major storm, known as the 1-in-100 year storm, had become almost 30% wetter. Instead of 13 inches of rain, it now dropped almost 17 inches of rain in Harris County.

“It may have been a case of: be careful what you wish for,” says Craig Maske, chief planning officer at the Harris County Flood Control District. “We did anticipate it increasing somewhat, just not quite that much.”

Beefing up infrastructure at a cost

The new information had a ripple effect through the various entities in Houston responsible for the metro area’s infrastructure. Rainfall numbers not only determine how stormwater systems are built, but also roads, highways, bridges and housing developments.

“Everybody, after taking the collective gasp of seeing how the rainfall depths had increased, knew this was going to affect how they developed and where they developed,” Maske says.

Transportation agencies suddenly faced building their projects to withstand more water. The Houston-Galveston Area Council, which oversees transportation planning in the area, says major projects in planning stages became $150 to $200 million more expensive, largely due to the flood safety needs. One-third of the major roads and highways there are vulnerable to flooding, according to an agency analysis, including critical thoroughfares needed by first responders in a disaster.

Despite the added cost, experiencing a record-breaking disaster seemed to change the conversation in the community.

“The fallout from Hurricane Harvey is still ongoing here,” says Craig Raborn, director of transportation of the Houston-Galveston Area Council. “So when we do public engagement processes for major infrastructure projects, major roads, we hear a lot more comment now about flooding than we used to see in the past.”

Extreme storms getting more extreme

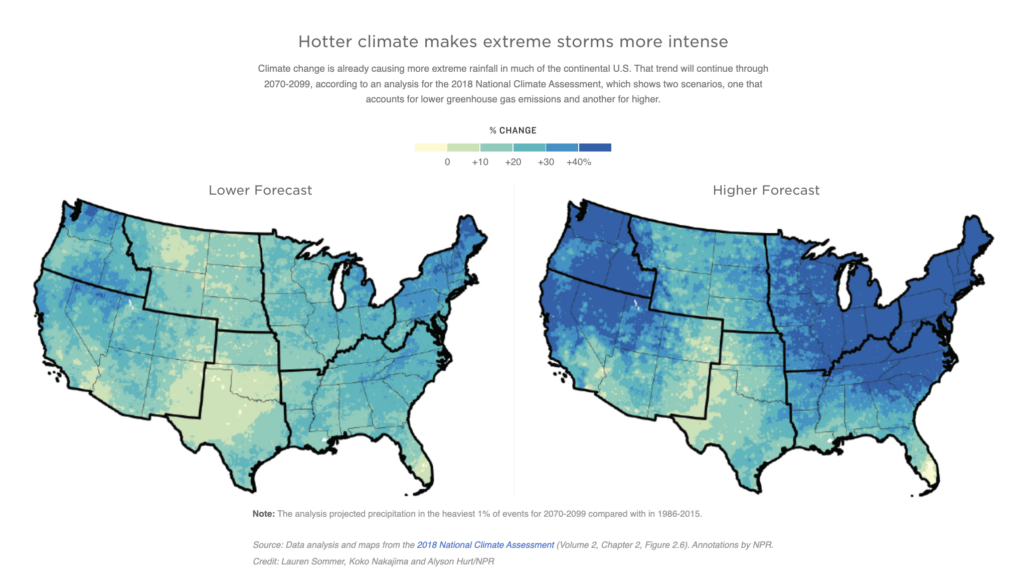

As temperatures get hotter, heavy storms are producing more rainfall because warmer air can hold more water vapor.

“Throughout most of the country, big storms are happening more often,” says Daniel Wright, assistant professor in civil and environmental engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “There’s every reason to expect that rainfall will continue to intensify in the future.”

The Northeast and Midwestern U.S. have seen the biggest increases, with the heaviest storms producing 55% more rain today in the Northeast compared to 1958, according to the 2018 National Climate Assessment.

Outdated rainfall records don’t reflect those changes. Wright and his colleagues looked at the Atlas 14 reports and found that in some places, extreme storms are happening twice as often as those reports predicted.

Under its current system, NOAA only updates the Atlas 14 information when states both request and pay for the reports. As a result, many states are using data from the early 2000s. The last update for the Pacific Northwest was in 1973.

Officials at NOAA say this haphazard system is far from ideal, since it creates a patchwork of climate data. Analyzing data for only a few states at a time also adds to the overall cost.

“It would be much more efficient to do the whole country all at once,” says Mark Glaudemans, director of NOAA’s Geo-Intelligence Division, which oversees Atlas 14. “So by doing it in the piecemeal fashion that we have now, it does make it more expensive.”

Updating precipitation data is briefly mentioned in the $2 trillion infrastructure bill passed by Congress last year. NOAA officials say they’re currently developing the agency’s spending plan for the funds and can’t comment on whether Atlas 14 will be part of it.

Flood experts are urging the agency to prioritize nationwide rainfall reports. Without that information, cities aren’t able to strengthen their infrastructure to handle today’s storms, as Houston is doing.

“The cost to do this is almost decimal dust when it comes to the overall federal budget,” says Berginnis, whose group wrote to NOAA about the matter. “We’re only talking about $3 to $5 million dollars a year to produce these data.”

Two bills now pending in Congress would also commit NOAA to doing regular updates, beyond what the infrastructure bill provides for the next decade. The PRECIP Act specifies that Atlas 14 would be released every 10 years, while the FLOODS Act would set the updates for every five years.

Cities lack climate change forecasts

Still, even with the most up-to-date rainfall information, climate scientists warn that infrastructure is still likely to fail, since NOAA’s Atlas 14 reports look at the past, not the future.

Nationwide studies, like the 2018 National Climate Assessment, show extreme precipitation will continue to get worse around the country as temperatures get hotter. A study last fall from the Northeast Regional Climate Center found extreme rainfall in New Jersey would likely increase by 20% by 2100, as compared to 1999. Some counties could see a 50% increase.

But when cities look for climate-driven rainfall information tailored to their region, they’re mostly out of luck, since NOAA doesn’t conduct that analysis.

“There’s no book,” says Anna Roche, project manager at the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. “There haven’t been plans that have been developed for any of this stuff. So every city in the United States is grappling with this.”

San Francisco, along with a handful of other cities around the U.S., have partnered with local universities and researchers for localized climate change projections, in the absence of relevant information from NOAA. San Francisco is working with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory scientists, who are running complex computer models that forecast future rainfall change.

In the Pacific Northwest, both Portland and Seattle partnered with the University of Washington’s Climate Impact Group. The research team created an online tool so cities in Oregon and Washington could see how extreme rain would shift. In Seattle, the 1-in-25 year storm could be more than 20% worse by the 2080s.

Realizing the scale of that change, Seattle enhanced a major stormwater control project that was underway. The Ship Canal Water Quality project was planned with a 14-foot diameter tunnel, designed to capture stormwater so the system isn’t overwhelmed in big storms. The climate change projections spurred the city to upsize it to 18-feet wide.

“We’re thinking this is a 100-year investment, so we need to be using our best information about what 100 years is going to look like and not designing things now that will be obsolete,” says Leslie Webster, drainage and wastewater planning manager at Seattle Public Utilities. “We’re confident that the change in sizing will provide a lot more resilience in the future. But, you know, it also increased the price tag significantly.”

Still, while major cities are beginning to integrate climate data into their planning, smaller cities without connections to leading universities have little information to go on. Many are urging NOAA to release climate projections, along with a new nationwide Atlas 14 update, to provide reliable information for infrastructure planning. Other federal agencies already provide localized climate projections, like the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s map showing how plant growing zones could shift.

“Rural and smaller communities simply don’t have the resources and typically access to technology to make those estimates,” Berginnis says.

The added cost of preparing for climate change comes at a tough time for most cities, which already have a backlog of maintenance for their stormwater systems. In 2020, municipal utilities nationwide faced a combined funding shortfall of $8.5 billion dollars, according to a study from the Water Environment Federation.

“Municipalities are facing an unbelievable gap in trying to keep up with stormwater,” says Darren Olsen of the American Society of Civil Engineers. “It’s expensive to upgrade infrastructure and stormwater infrastructure, because it’s out of sight, it’s out of mind.”

Upsizing a city’s entire stormwater system, with miles of underground pipes that would need to be dug up, is far too expensive for most cities. Instead, many are looking at using green infrastructure, where pavement is replaced with plants that allow rainwater to soak into the ground. The hope for many is that the infrastructure bill provides much needed funding to make their systems climate-ready with both traditional and green projects.

“I do think it’s like a cultural shift that we have to make in terms of how we plan for our future,” says Nishant Parulekar, civil engineer with the City of Portland. “We’ll have to be very adaptable in terms of how we plan and build.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))