After the spotlight: How a book ban fight changed one Pa. community

A book ban put the Central York School in the national spotlight. Meet the people who defeated it — and discover how it changed them.

Listen 23:43

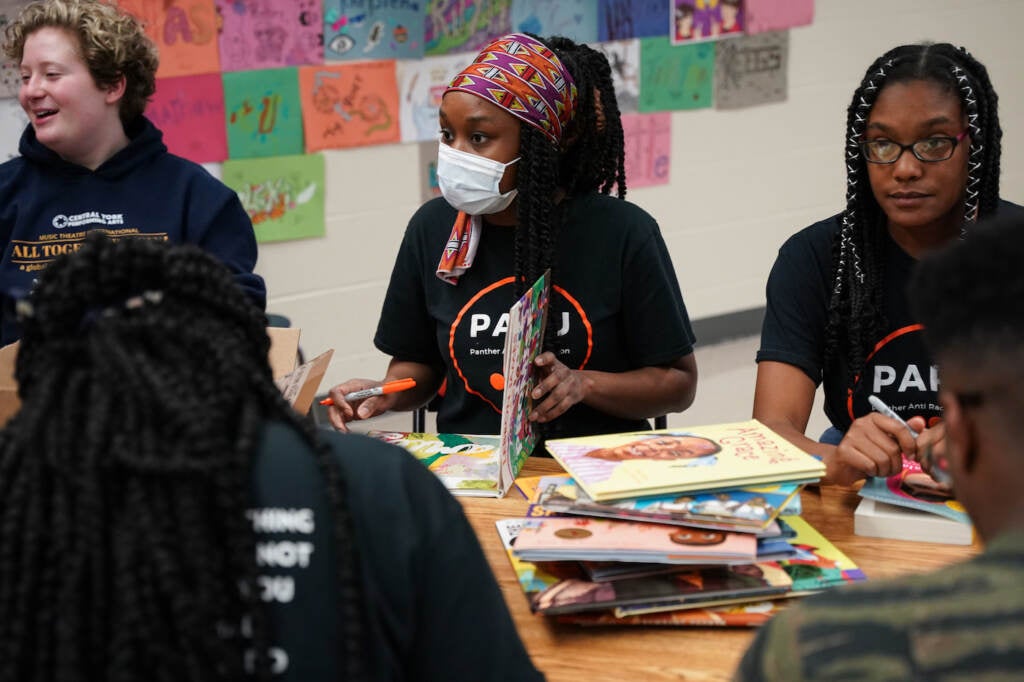

Students gather during a meeting of the Panther-Anti-Racist Union at Central York High School. When the school board barred educators from using hundreds of teaching materials in their classrooms, the group organized peaceful protests. (Matt Smith for WHYY)

This is the third episode in the 2022 season of WHYY’s podcast “Schooled,” which tells the inside stories of people in our K-12 education system.

Note: The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

___

Avi Wolfman-Arent: By now it is a familiar story. All across the country, books are getting banned from school classrooms or pulled from library shelves.

Newscaster 1: Around the country efforts to ban specific books or even whole categories of books …

Newscaster 2: We’ve reached the inevitable book-banning, purge list portion of the …

Newscaster 3: … challenge these books saying they contain inappropriate material for students. Now the district has formed a committee to review the books.

AWA: There’s a range of claims about these books. That they’ll make white kids feel bad about themselves or guilty. Even that they’re pornographic.

Parent: Does equity and inclusion also include incestuous relationships?

AWA: Between last July and this March, there were book bans in 86 school districts across 26 states, according to a report from PEN America. It defines bans as any instance where a book has either been made harder to access or removed entirely. Over 1,100 different books were challenged.

Pennsylvania was not immune.

In this two-part episode, we’re visiting two school districts with very different book ban stories: Central York and Central Bucks.

The fact that both of these districts have “Central” in their name is telling. Both are suburban districts — the kind where people of different races and religions and political persuasions mix.

And they are — in their own ways — microcosms of America. Right now, both are at the center of a very American fight over who belongs.

This is “Schooled.” I’m Avi Wolfman-Arent.

In the first of these two episodes, we’re taking you to the Central York School District. It’s actually just outside the city of York — which is in South-Central Pennsylvania, right near the Maryland border.

It’s one of those places that is diversifying fast. A decade ago, about 24% of Central York students were students of color. Today, it’s 36%.

And amid that shift, Central York recently found itself in the national spotlight.

One note before we begin: This episode does contain references to sexual assault.

Reporter Mallory Falk takes it from here.

Mallory Falk: Let’s start this story on a quiet cul de sac, where a woman named Erica Bowie lives with her two daughters and their trusty guard dog, an elderly Shih Tzu.

Erica Bowie: His name is Buster, and our old man will be 14 in September. He’s partially blind and deaf. He’s always gonna bark when someone comes in the house. So that still works.

MF: Erica moved to Central York from Baltimore, where she still works as an auditor. It’s a pretty common story here. Over the past decade or so, lots of families have moved here from bigger cities. It’s kind of a crossroads of America — with urban, rural, and suburban distrcts, all in one county.

EB: We moved here for the resources. The schools were better. It was less populated. We could move slower. The cost of living was so different and so much cheaper. Nothing like I’d experienced.

MF: She felt like her kids were in good hands when they started at the Central York School District. Then one day last September, she got a call from her grandmother.

EB: She was like, “Hey, what’s going on up there in York, Pennsylvania?” I was like, “I don’t know.” And she was like, “Well, apparently you can’t read any books by any Black people.” And I was like, “I don’t think that’s true.” So I cut the TV on and it’s on there.

Newscaster 4: In York County, students at Central York High School holding a protest this morning in response to the school district banning materials by Black and Latino authors that discuss race in America.

Newscaster 5: That list includes a children’s book about Rosa Parks, Malala Yousafzai’s autobiography, CNN’s “Sesame Street” town hall on racism.

Elmo: Racism? What’s that?

Newscaster 5: And much much more.

MF: OK, so what actually happened? Why had the national media descended on this sleepy suburban district in Central Pennsylvania?

Back in 2020, after Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin’s murder of George Floyd and nationwide protests for racial justice, the district’s diversity committee got together. They came up with a list of resources teachers could use to help students process what was happening.

It included hundreds of books and other materials, like documentaries. But then the school board stepped in and barred teachers from using those resources.

They said they had received complaints from parents and wanted to review everything on the list before they’d approve it.

But that review process never happened. By the following school year — fall of 2021 — the list was still frozen.

This all happened pretty quietly. That is, until the high school principal sent out an email at the start of the school year, reminding teachers not to use the banned materials.

A local paper, the York Dispatch, picked up the story. That’s how a lot of people found out, like Renee Ellis, a junior at Central York High School.

Renee Ellis: They don’t say that it’s directly targeting people of color and authors of color. But when you look at the resources that they banned, it’s pretty evident.

MF: Scrolling through the list, she saw a couple of books that had meant a lot to her back in middle school, some of the first ones she’d read with Black characters at the center, like “The Hate You Give” by Angie Thomas.

RE: They helped me to feel less alone in a school where I didn’t see a lot of people that looked like me. So those books were just — they felt safe, in a way. That sounds weird, in a book. But when you find something that you can relate to and that you can connect to, it makes you feel a little less alone in a world that’s kind of against you, in a way.

MF: Seeing them on the list …

RE: It just hurt because I knew how important they were to me and I knew they could be important to someone else as well.

MF: Parent Erica Bowie had a similar reaction. She saw the list included children’s picture books — about a young Black girl who loves science and another who loves styling her hair. She thought about her younger daughter, a second-grader at the time.

EB: It denies my daughter a sense of belonging. To me, it’s saying you don’t belong. To me, my daughter gets the message that you don’t belong here, but we tolerate you.

MF: And she thought about that decision to move to Central York about a decade ago.

EB: It’s kind of like, so you moved out here for the resources that aren’t even including you.

MF: Renee would end up helping organize protests against the ban — every morning, outside the high school, for weeks. They would grow and gain attention, with people like Erica joining in. And eventually, the school board reversed the ban.

RE: We made an impact. And it was good. And I’m glad that it was reversed. We were all really excited.

MF: It’s a little unusual to tell you how this story ends at the beginning.

Normally, we’d start with that moment when news of the book ban spread and build momentum and tension as we followed the fight against it. Maybe end with the scene when a couple of the students testified in front of Congress during a hearing about book bans and academic censorship.

Christina Ellis: Banning books of those of minority background and unique backgrounds silences their voices and erases their history and arguably is taking away their right to express themselves. These are words on the page that have the power to change a cold heart to warm. It’s not indoctrination, it’s education. Thank you.

MF: That was Renee’s older sister, Christina.

But we wanted to give you something you don’t normally get.

All over the country right now, there are battles over books and school curriculum — about how history is taught, and whose stories are included.

But who are the ordinary people who take a stand as these fights play out? What compels them to get involved? And how does this experience change them?

Eli Holland-Garcia: It’s really universally cosmic how them being so hateful and so outwardly, just, disgusting towards us and towards this book and everything actually helped heal me.

MF: Patricia Jackson teaches language arts and creative writing at Central York High School. Books and stories are her thing. But at first, she was a little hesitant to get involved with the student protests. Patricia grew up here in York County, in what she describes as a mostly white world.

Patricia Jackson: I rode horses for goodness sake.

MF: And for most of her life, she tried not to draw much attention to herself. It’s a lesson she learned from her dad. He grew up in Alabama in the ‘30s and ‘40s. Patricia says, as a kid, he witnessed a gruesome lynching, and it shaped how he moved through the world. That had an impact on her.

So did growing up as a Black sci-fi nerd in a white community. She’s a big “Star Wars” fan — even has a special drawer in her classroom with not one, not two, but three lightsabers. She jokingly waves them at students who need to settle down. But that franchise — and the others she loved as a kid — doesn’t have leading Black characters.

PJ: Even if you have the token Black person in there, they’re not center stage. They’re the ensemble cast.

MF: She didn’t see herself represented in her community or in her favorite stories. So when she started writing fiction, as a kid …

PJ: My characters were blue-eyed and fair-skinned and blonde-haired, because that’s what the world told me was beautiful. It was not until my 20s — when I started writing “Star Wars” fiction — that I started to say, “Oh, well, this character is dark-skinned.” But that’s all I would say.

MF: Then, a few years ago, she started to write what would ultimately become her first published novel. It’s called “Forging a Nightmare.”

PJ: My book is about an FBI agent who is tracking down a serial killer, who is taking out people born with 12 fingers and toes. And when he finds out that they are the Nephilim — descendants of angels — the only way he can save them is to saddle up as one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse.

MF: Early on, this secondary character came to her: a loud, proud Black woman.

PJ: Dreadlocks, the whole nine yards.

MF: It’s something that hadn’t happened before. And she started to reimagine her book. The protagonist — that dogged FBI agent — should he be Black, too?

PJ: And I’m like, well, he’s part angelic. Are angels Black? You know. So you go through this whole litany in your mind of: But we’ve never seen that before. So, yes, I made angels Black. And just did it proudly. And there was this freedom. And I call it my exorcism, where I came to love myself as a Black woman. Because at that point, I don’t think I did.

MF: Patricia describes this process as tending to a wound that either had to start healing or start festering. And it primed her to step up, when a fellow teacher asked for guidance after the resource ban. His name is Ben Hodge, and he’s the faculty advisor for the Panther Anti-Racist Union, or PARU, a student group that formed in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. The high school mascot is a panther.

Ben said his students wanted to protest the ban and asked if Patricia could help support them. The two are close. They trust each others’ judgment and bounce ideas off each other.

PJ: So he comes to me, and I don’t want to be involved. I want to keep things as quiet as possible and attract no attention to myself. But I see my friend being so passionate about this and I know they will come for him. And I cannot and will not allow that. Nor will I allow them to come for the children.

MF: After writing a book with a leading Black character, and coming to embrace her own Blackness, Patricia says she didn’t want to crawl back under a rock. She wanted to support those students — to serve as a kind of protective shield as they put themselves on the line.

So she got on board. And that had a ripple effect.

Remember Renee Ellis? That student who was so disheartened to see some of her favorite books on the banned list? She was like Patricia, someone who kept a low profile.

RE: I was naturally a little quieter than most people, especially in school. I don’t really say much. I’m just trying to get the good grade and get out.

MF: Her sister, Christina, is the extrovert, with the take-charge personality. She and her friends were the ones who started to talk about a protest. But Renee wasn’t so sure.

RE: I’m one of those people, I like to organize my thoughts and get things in order first before I move. When things happen spontaneously, you don’t have the opportunity to do that. So I was wanting to wait back, and then I also didn’t want to cause a fuss. I knew that it wasn’t right, but when you’re faced with a school board, you’re a little intimidated.

MF: Just a few days after learning about the ban, Christina hopped on a Zoom with other members of PARU, along with Patricia and Ben. Renee sort of lurked in the background.

RE: And I was listening to them talk. I was like, “I have a couple ideas.” You know, raising the one finger. And they were like, “OK.” And Miss Jackson told me — I was like, “Is it OK if I be a part of the group?” And she was like, “Listen, we’re going to do this. This is going to move. You’re drafted. Let’s go.” And so ever since then I’ve kind of just been on the train and we’ve been moving and growing as a group.

MF: This teacher who had been hesitant herself — now she was encouraging Renee, who, over time, became integral to the protests. For Renee and Patricia, the book ban unlocked something inside them. But there was another Central York student who already had that activist streak, who already was an outspoken kid. The book ban led him to reckon with something more personal.

There’s this idea that the best way to pique a kid’s interest in a book is to ban it. That’s exactly what happened with Eli Holland-Garcia.

Eli Holland-Garcia: The funny thing is, all of those people were like, “We need to keep the kids away from reading this. Prevent them from seeing it at all costs.” Yet them doing that is exactly what brought it to my attention to read it.

MF: Eli had tuned into a school board meeting where people were railing against one particular book: “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” by George M. Johnson. It’s a memoir about growing up Black and queer. And it’s been challenged in school districts across the country.

EHG: The one comment that I couldn’t get over was calling it porn when it was talking about a person’s experience as a child. It felt like I got punched in the chest with a jackhammer, emotionally, when I watched that. Because the whole point of that is to make gay people … is to sexualize them and then make them seem like less of a person.

MF: Eli decided he wanted to speak up at the next school board meeting on behalf of himself and other LGBTQ students. But he knew that before he defended the book, he should probably read it.

EHG: Mainly just to give me background. I had no intention of it becoming very important to me in a lot of ways. I had no intention of that. It was solely just to read it just to get a grasp of the information in it. But then I read it and I was like, “Oh, wow.” It made me cry and it made feel like I wasn’t crazy with a lot of the things I experienced as a child.

MF: Johnson wrote about getting beat up as a kid for being too feminine — something Eli also experienced. And he wrote about being sexually assaulted by an older male cousin. Remarkably, a very similar thing had happened to Eli.

EHG: And I always thought that it was my fault, that I was wrong and weird and disgusting and whatever for it.

MF: Sometimes he’d zone out — see it happening all over again — and then ask himself why he hadn’t stopped it. But reading Johnson’s account of a very similar experience reframed Eli’s understanding of what had happened to him.

EHG: Reading that made me really realize that it wasn’t my fault and that I’m not some weird, disgusting creature like other people make us out to be. Now I can look at it and be like: It’s not your fault. You were too young. You were too young to understand. And you were also scared because you had no representation or anything.

MF: This wouldn’t have happened if that book had never ended up on his radar.

EHG: It’s really universally cosmic how them being so hateful and so outwardly disgusting towards us and towards this book and everything actually helped heal me. And I feel like that’s just something really special, kind of. Their being so hateful helped me heal myself.

MF: This all strengthened his resolve to speak in front of the school board. Before, he was a little on the fence.

EHG: And then once I read the book, I hopped the fence, hopped over the frickin’ trench, ran through the frickin’ woods onto the other side of the continent and I was ready to go.

EHG (before school board): Good evening. Hi, I’m Eli Holland-Garcia, an 18-year-old student of Central York High School. And I want to say, first, thank you for your service to this district.

MF: And when Eli shared his story, the response was overwhelming.

EHG (before school board): I read the book this weekend and not only was it beautiful, it gave me an insight to my own assault that I would have never had otherwise.

MF: The room erupted in applause. Eli knows his one speech in front the school board doesn’t change everything. People are still speaking out against certain books. But he also wants to believe people can evolve — like his grandparents, who he says used to be very conservative. Now, they get excited for his drag shows.

EHG: I mean I send them my makeup looks. My grandpa has, in the past, sent me makeup looks. He’s like, “You need to try this.” And so they’ve come such a long way. So I know people can change. I just know that it also sometimes takes 60 years.

MF: In a lot of ways, what happened in Central York is a success story. A small group of students decided to fight back against a book ban. Their movement grew, and received national attention. And they won. Now, they’re a model for other student activists.

It even led to the election of school board candidates who opposed the ban. Again, student Renee Ellis.

RE: Coming from a Black person’s perspective, there’s people who believe you should be dead, or not in this country, or inferior, or enslaved. So you just have to go through that. You have to know how to best survive that. So when we came to those community protests, and there was a whole bunch of people there it was like, “Whoa, this is our community.” That was really encouraging to see because you have those select few that — a little scary. And then you have those people that show up and they show out and they really support students.

MF: Renee’s dad says he used to worry about her, because she was so shy. But over the past year, he’s watched her blossom. That quiet girl is now the director of communications and outreach for the Panther Anti-Racist Union. When she gets to college, she wants to minor in political science so she can continue her activism.

But the move to censor books hasn’t stopped. Teacher Patricia Jackson says both she and her mom received threats after she started speaking out. And for some, it’s hard to unsee the side of the community that this fight exposed.

That brings us back to Erica, the mom you heard at the beginning of the story. Yes, the board lifted that freeze on teaching materials. But the fact that they were frozen to begin with — Erica says it confirmed something she hadn’t wanted to admit.

EB: You know what the book ban really, really did? All of that, “It’s not racism, it’s something else. It’s a bad day.” The book ban made it like: “Oh, no, that is what it was all that time.”

MF: It’s changed how she views some of what she — and her kids — have experienced in York. She’s re-litigating all these past moments. And now, when something feels off, she wonders if it has to do with race. Like recently, when she says her older daughter texted from school to say she’d been called into the office and told to cover up.

EB: It’s warm outside. She has on a crop top, which all of the girls are wearing. But why, you know? So before the ban I don’t know if I would have just put race, pop, right in my mind when she sent that to me. But of course race pops right into my mind.

MF: Whether race is at play or not, it’s exhausting to always have that seed of doubt. All of this has made Erica wonder if her family should stay in Central York. She moved here because it seemed like one of the better places to raise her kids.

EB: Does better equal white? And it shouldn’t be like that. Better should just be better. I wanted better for my kids, so we moved out here. But my daughter doesn’t have any friends that look like her. All of her friends are beautiful little white girls and she’s the only beautiful little Black girl. It’s hard for her to identify — if all of the books in her school look like all of her friends. And none of the books in her school look like her. It’s just hard.

MF: Students like Renee Ellis are working to help make sure that won’t be the case. At a Panther Anti-Racist Union meeting this spring, she pointed to a table piled high with picture books — with stories about a Mexican family making tamales for Christmas and a Black family passing down musical traditions.

Renee explains they’re headed for a community bookshelf.

RE: And so we actually purchased books to donate to their bookshelf. We would love it if you guys could sign the books. Put inspirational messages to the kids. Put PARU stickers on there, just as a way for us reach out to the community, right? To do something good for the children.

MF: The students grab sharpies and get to work. “You’re amazing,” they write. “Keep dreaming.”

AWA: “Schooled” is produced by WHYY in Philadelphia. This episode was written by Mallory Falk. It was edited by me, Avi Wolfman-Arent, with help from Emily Rizzo. Engineer Mike Villers helped mix the sound. WHYY’s vice president of news is John Mussoni. For more information on “Schooled,” visit WHYY.org/schooled.

Next week, in part two, we travel to Central Bucks in the Philadelphia suburbs. A different fight over books and representation, with a very different outcome. Stay tuned.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.