Woodmere offers new look at Violet Oakley, whose murals stand timeless at Pa. Capitol

The Woodmere Museum in Philadelphia's Chestnut Hill neighborhood will host an exhibit of the work by Violet Oakley, once one of Pennsylvania's most prominent artists.

-

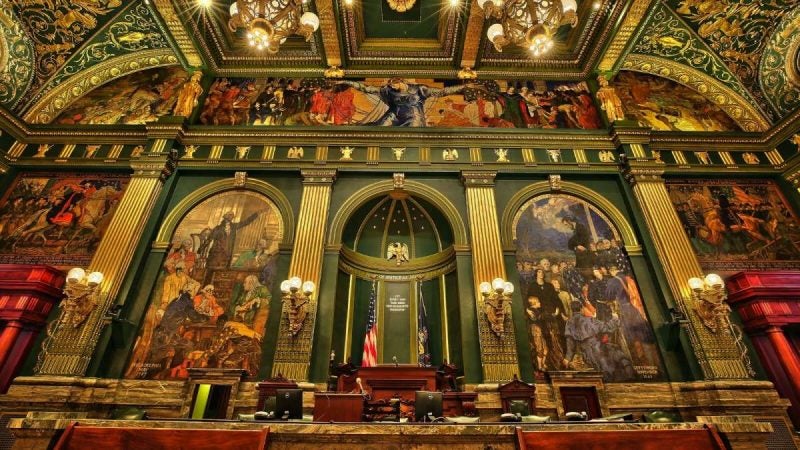

Although they're a hundred miles away, the murals in the Senate Chamber of the Pennsylvania Capitol in Harrisburg are a significant part of the new Violet Oakley exhibit at the Woodmere Art Museum. (Woodmere Art Museum)

-

A silhouette shows the actual size of Abraham lincoln in Violet Oakley's Senate chamber mural. The work is explored in the Woodmere Art Museum exhibit ''A Grand Vision: Violet Oakley and the American Renaissance''. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Violet Oakley was commissioned to paint the lunettes for a domed entrance hall in a private residence in Philadelphia. The missing piece was recently recovered and was restored for the show. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A detail from the lunette shows members of the Charlton Yarnal family, who lived in the home at 17th and Locust streets. The murals were removed when the building was converted into offices. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

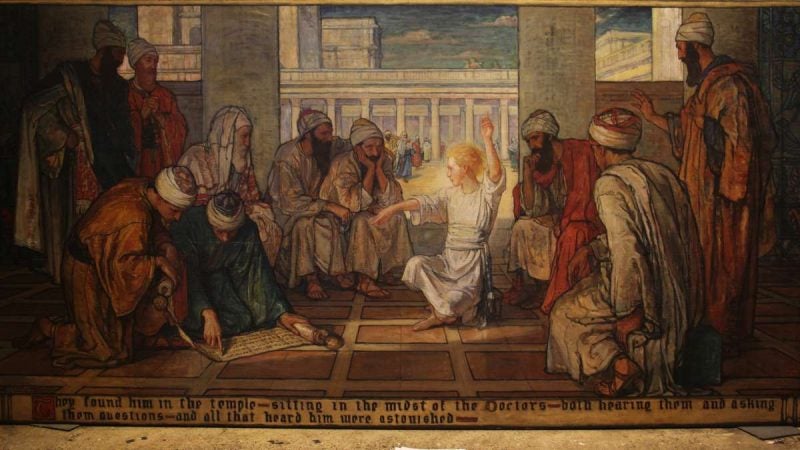

Violet Oakley's mural depicting young Jesus teaching in the temple was commissioned to inspire the students at Chestnut Hill Academy. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Violet Oakley, 1874 - 1961, painted this self-portrait in 1919. (Glenn Castellano)

-

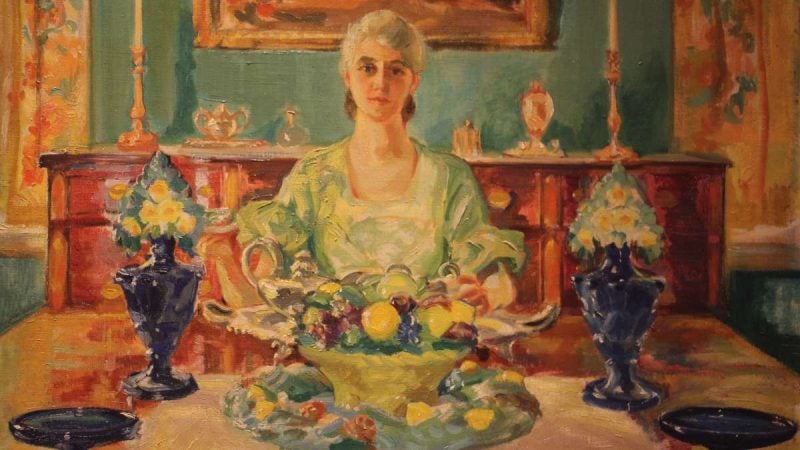

A portrait of Violet Oakley painted by her life partner, Edith Emerson, is included in the exhibit. (Woodmere Art Museum)

The Woodmere Museum in Philadelphia’s Chestnut Hill neighborhood will host an exhibit of the work by Violet Oakley, once one of Pennsylvania’s most prominent artists. Best known for the murals she painted in the state Capitol building in Harrisburg, she led a busy career of public and private commissions spanning six decades.

“Violet Oakley had an incredible career, but today you cannot find her name in textbooks about American art,” said Patricia Ricci, curator of “A Grand Vision: Violet Oakley and the American Renaissance.”

“I think it’s because she was marginalized as a woman artist. She still belongs in a box of ‘women who did things first,’ and never entered the mainstream.”

The Harrisburg murals, started in 1905 and finished 25 years later, represented the first art project in an American government building commissioned to a woman.

“Art lovers generally don’t go to Harrisburg,” said William Valerio, Woodmere’s president and CEO. “Government officials do, but not lovers of art. Hopefully that will change.”

The Woodmere Museum could not bring those murals to Chestnut Hill, of course — they still preside in the Governor’s Reception Room, the Supreme Court room, and the Senate Chamber. So curators did the next best thing; they took high-definition pictures of them — the first time they have been properly photographed, according the museum — and tapped Oakley herself to explain.

In 1955, on the occasion of an exhibition of her work at the Harrisburg library, she gave a tour of the murals in the Capitol. The nearly 100-minute walking lecture — largely about the founding of Pennsylvania as Quaker William Penn’s experiment in religious tolerance — was recorded.

“My hope in doing the work was not only the miracle of Penn’s ‘Holy Experiment’ would be recorded as history, but that the holy experiment might live again,” said Oakley, who died in 1961 at age 86.

The gallery at the Woodmere Museum features large-scale photographic reproductions of the mural, and a video projection of the Capitol rooms narrated by Oakley’s archival recording.

“It is the pilgrimage of a painter seeking peace,” she said. “Not the cessation of action, but of course the cessation of all hostilities. Peace means constant vigilance, truly a diligence in love.”

Healing inspiration

While designing some the imagery for the 43 murals, she was in England juggling other projects. She recalled a stormy night in London when she could not figure out how to adequately tell the story of Penn in pictures — from his persecution as a Quaker in England to his “Holy Experiment” of religious tolerance in America.

“I thought the Thames was a good place to jump when you knew you couldn’t carry out what you were asked to do,” said Oakley.

Feeling despondent and desperate for inspiration — and to get out of the rain — Oakley ducked into the National Gallery in London.

“My hair was coming down, and the wind was blowing, and the rain was pouring, and I was very miserable indeed,” she said. “With difficulty, I climbed all those steps to the central hall and dropped upon a bench in the center.”

“I looked up and saw a beautiful Italian painting, an early painting. I suddenly realized that time had nothing to do with art. Art was not for an age, but for all time. It was the expression of the eternal qualities of beauty and harmony,” she said. “And I was immediately healed.”

The story of Violet Oakley is often told by how she lived her life — as a young woman she shared a house in Philadelphia with two other working artists. They called themselves the Red Rose Girls, and their situation was frowned upon by many in society.

Violet stands out amid Red Roses

Later, she established a lifelong, committed relationship with another woman, Edith Emerson, who was the Woodmere Museum’s director for many years. As such, the museum has become a kind of unofficial repository of Oakley’s work, with an inventory of about 2,000 pieces.

Oakley is certainly not an unknown figure to Philadelphia art lovers and history buffs. Her work often appears on the walls of the Woodmere, in particular, but Valerio wanted a more ambitious exhibition that showed the breadth and length of her artistic life.

“An exhibition that shows Violet Oakley not as a Red Rose Girl — which was really a small part of her career — but an exhibition that shows her to be the major figure in art that I believe she is,” he said. “The story had to be told.”

Like the whole of Oakley’s career, “A Grand Vision” is anchored by the Harrisburg murals. The work established her reputation at an early age, and the historical research she did to accomplish it — particularly into Quakers and William Penn — shaped the soul of her subsequent work.

Raised in the Episcopal faith and later converting to Christian Science, Oakley adopted the political philosophy of Quakerism. Her Capitol murals show conflict between the forces of capitalism and the military against the oppressed. Slaves are prominently featured.

“She was critical of American policies,” said Ricci. “Most mural painters celebrated America. They would imitate Renaissance religious paintings, and typically had a woman enthroned who represented America or Justice, with angels holding plaques. Through her study of Quakers, Violet Oakley tackled religious prejudice, racial prejudice, and gender conflicts. She put that into the murals.”

Although she may have intended to make art “not for an age, but for all time,” Oakley’s work included contemporary figures, such as Jane Adams helping the poor on one side, facing off against uniformed World War I soldiers on the other. That mural explicitly critical of militarism was hung in 1916, right before the United States entered the first World War. Had she finished it a few months later, she might have been arrested for sedition.

“It’s an interesting contradiction,” said Ricci. “It’s a remarkable combination of contemporary and historical figures. Just not done in mural painting by anyone but Violet Oakley.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.