Whether painting or working in stone, Elyn Zimmerman keeps her hands dirty

A new art movement was taking shape in Southern California in the early 1970s. An outgrowth of Minimalism, building on the idea that the world didn’t need more objects, the Light and Space movement put the viewer into the space to perceive the work and, through this perception, help create it.

Elyn Zimmerman, a Philadelphia native, was a grad student at UCLA at the time, and the Light and Space movement had a profound influence. Elyn Zimmerman: Wind, Water, Stone, a major solo exhibition, is on view in Grounds For Sculpture’s East Gallery through January 7, 2018.

Zimmerman is best known for her large-scale monolithic installations in granite, marble and limestone, situated in public spaces surrounded by reflecting pools. The transport of these massive works to the Hamilton-based sculpture gardens is, alone, a major feat, requiring cranes and forklifts and heavy lifting specialists. The exhibition is rounded out with Zimmerman’s works on paper.

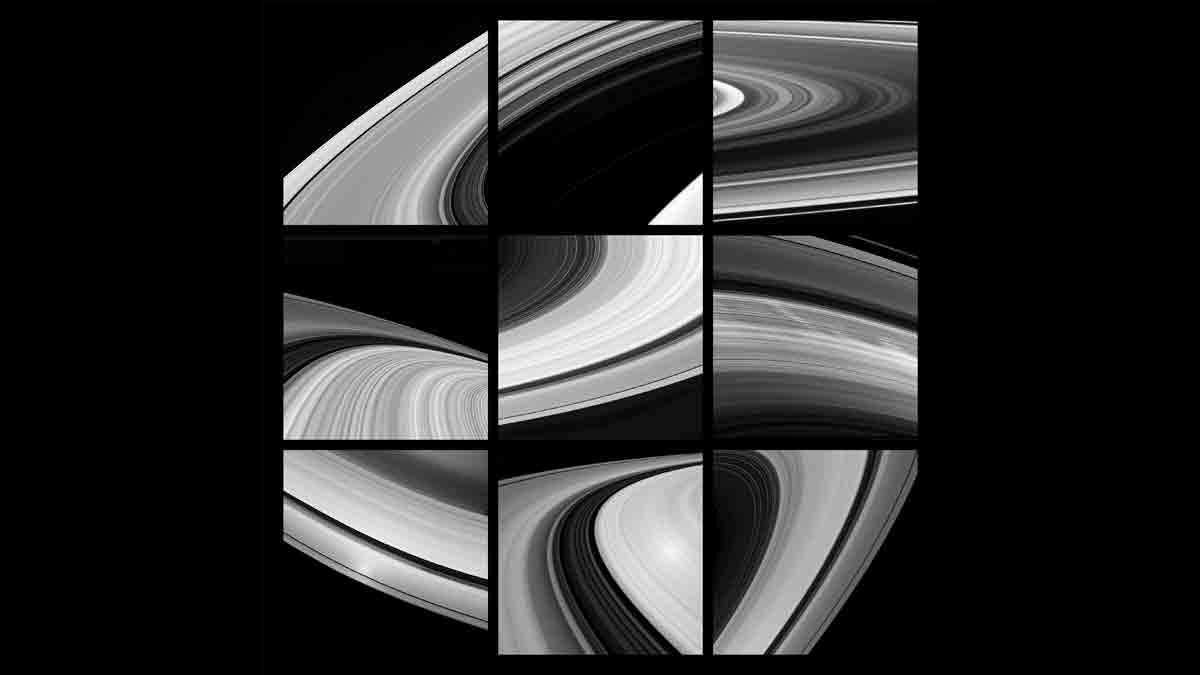

The 2016 winner of the Isamu Noguchi Award—it “recognizes innovators aligned with the global-mindedness embodied in the craft of trailblazing” sculptor Noguchi—has been exhibiting drawings and photographs since earning an MFA in painting and photography from UCLA in 1972. The East Gallery focuses on her public sculptural works and the relationship of these to her archeological photography. Stone sculptures are on display in the adjacent outdoor hedge gardens. The West Gallery will further explore Zimmerman’s works on paper, juxtaposing recent photographic collages of the night sky with lush pastel drawings of clouds, beginning in February.

Her public commissions can be seen from New York City and Washington, D.C., to San Francisco and Vancouver, Canada. Closer to home, Zimmerman’s public art is situated along the pond at the Institute for Advanced Study—a piece commemorating the Institute’s 75th anniversary. Consisting of three curved granite panels 40 feet in length, it is suspended from and surrounded by groupings of powder-coated stainless steel poles of varying heights and thicknesses and appears as a sinuous bench floating amid slender trees. Each of the sculpture’s three benches is inscribed with a quotation from key figures in the Institute’s history, including Albert Einstein. Visitors, among them leading scientists and scholars, are invited to stop, sit and contemplate the surroundings.

At UCLA Zimmerman studied painting with Richard Diebenkorn and photography with Robert Heineken before joining James Turrell, Robert Irwin and their circle of Light and Space artists.

“I was fortunate to be both an undergraduate and graduate student with this group of artists who began questioning the art object, that it is something you experience, not a thing,” Zimmerman recounts. “You didn’t have to have a permanent art object to create an experience, so they began doing exhibits in empty store fronts or in studios. What you’d see would be light coming in through the windows in a certain way, or sound controlled in a certain way. It’s how you perceive and experience the world. We are constantly assaulted by noise from TV, the street, and now the internet—we’re distracted and not paying attention. They wanted us to pay attention, to attend to something in a new way. It grew out of the ’50s and an interest Zen Buddhism, meditation and distilling things to an essence.”

Among the other groups that influenced her were the Earthwork artists. “In the late 1960s art world, painting was dead,” she says.

Zimmerman lives and works out of a loft on Soho’s Greene Street. When her late husband, Kirk Varnedoe, the chief curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art from 1988 to 2001, was alive, she had a separate studio six blocks away, on Franklin Street. After his death in 2003, the 3,200 square foot space that floods with natural light from five 12-foot-high windows on both the front and back, seemed enough.

She met Varnedoe in 1974 when, as an art historian at Columbia University, he reviewed her work in the Whitney Biennial for ARTnews. Their lives together were filled with travel, scuba diving and ice skating, opera and reading poetry aloud. Varnedoe was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1996; he stepped down from MOMA, and the Institute for Advanced Study offered him a position, knowing his cancer was terminal. She and Varnedoe moved to Princeton, and Zimmerman commuted to her studio in New York but enjoyed dinners in the Institute dining room with faculty. Varnedoe died a year and a half later, at age 57.

Zimmerman was comforted by Varnedoe’s Institute colleagues. His collection of art books was donated to the Institute library, and Jasper Johns made a commemorative book plate.

Among Zimmerman’s losses is a monument she created for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing—it was destroyed during the 2001 attacks. ”Here I made a memorial out of a couple of tons of granite, and you think it’s not going anywhere ever, and then, something like this happens, something inconceivable, and you realize that people, things just disappear,” she said.

These days, she only works in stone when she has a commission. “I’ve always been interested in drawing and painting,” she says. “Pastel is a nice medium, I like the colors and density. I like working with my hands and getting them dirty.”

________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.