What does an equitable city street look like?

Bike safety advocacy has a problem. While a significant share of the growth in bicycle ridership in recent years has been coming from non-white, lower-income riders, the people elected officials most commonly hear asking for better bike infrastructure are disproportionately white and higher income.

Because of who’s asking, many elected officials and political observers appear to have developed the impression that white professionals are the group that stands to benefit most from street safety improvements like protected bike lanes, and that limits the appeal of these types of interventions as a political priority. For many politicians who want to trumpet their pro-equity bona fides, bike lanes are often the go-to example of the sort of unserious business they would deprioritize in office.

The cycling advocacy community seems to be putting some serious thought into overcoming this political challenge, as evidenced by the “Bikes +” theme at this year’s National Bike Summit, which will look at “how bikes can add value to other movements and how our movement can expand to serve broader interests.”

There is also a challenge in that many of the traditional Democratic interest groups in large US cities aren’t quite sure yet whether to let bicycle advocacy, or urbanism more generally, into the club. To borrow Patrick Kerkstra’s distinction between the Michael Nutter/Paul Levy side of Philadelphia’s Democratic Party, and the Bob Brady/John Dougherty side, the bicycle advocacy community is firmly rooted in the Nutter/Levy camp.

So one way to think about this new “Building Equity” report from the advocacy groups Alliance for Biking and Walking and People for Bikes is that it’s presenting the case for how “complete streets” policies complement and reinforce broader progressive movement goals like equity and affordability.

The first thing they do is situate the current moment within the troubled class and racial history of transportation and planning politics:

American urbanism has been a process through which communities—diverse in ideology, in interest, in income, in ethnic background and in racial identification—have negotiated space. Some of this evolution has been brutal. Today’s cities are, among other things, the result of generations of racism and classism and struggles in the face of those discriminations. As decades and centuries have gone by, racial boundaries in the United States have shifted; discrimination has remained. Transportation has been near the heart of that struggle from the start. From housing choice to bus frequency to freeway routing to sidewalk quality, cities have often failed to equitably distribute the costs and benefits of mobility.

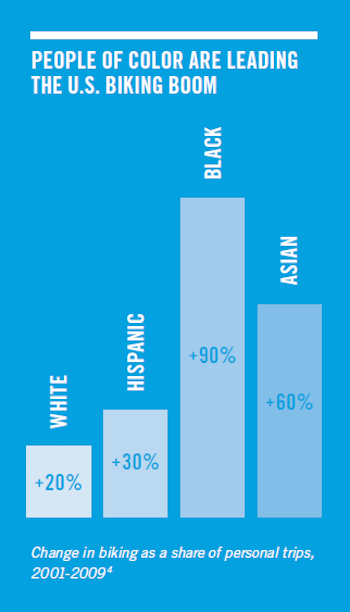

From there, they point out that (nationally, at least) people of color are leading the increase in bicycling, and whites actually account for the smallest percentage of the growth.

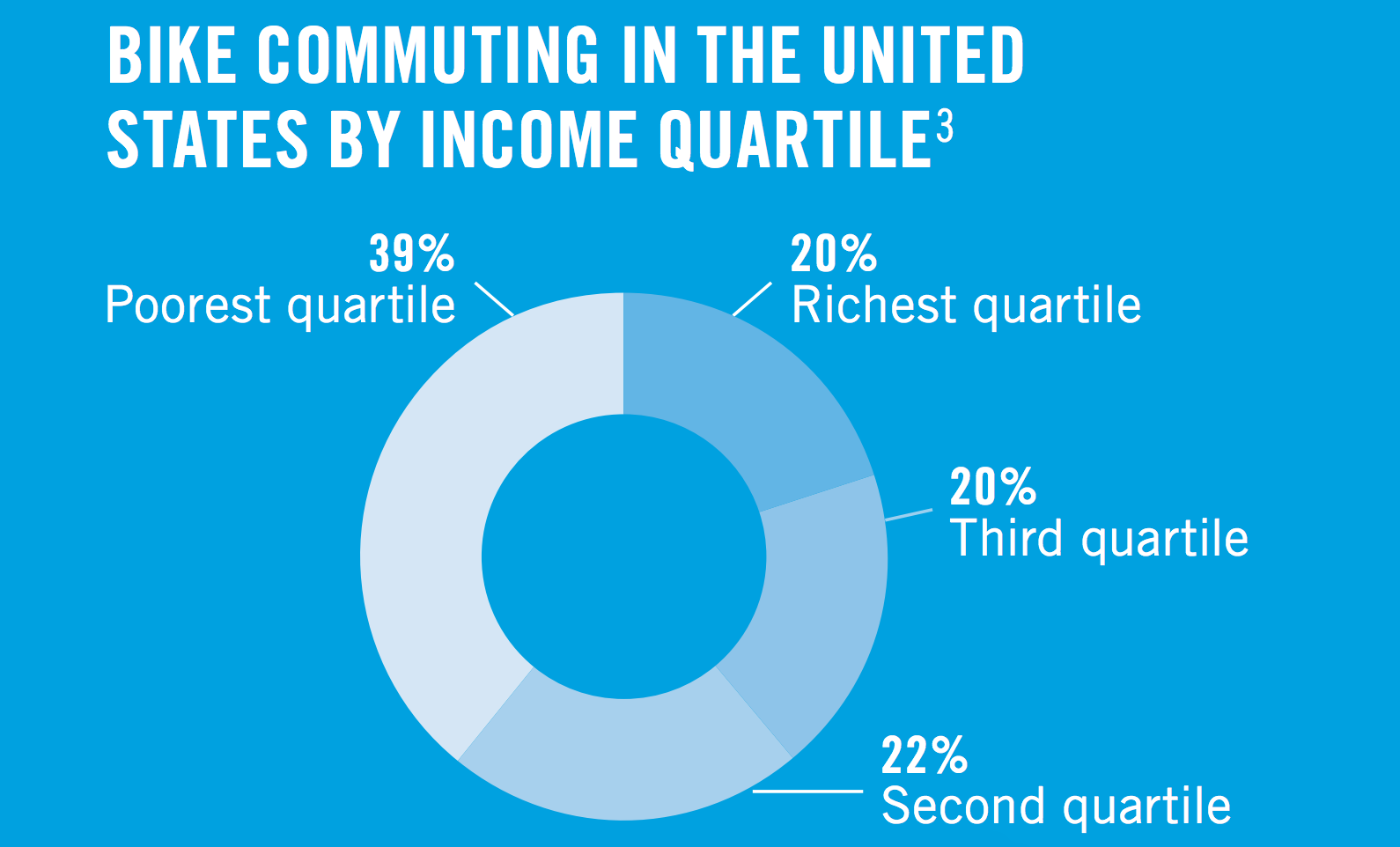

And looking at it in terms of income, the poorest quartile makes up the largest percentage of bicycle commuters nationally.

Some other facts of note:

- African-Americans are significantly more likely not to own a car than white households

- Latinos and African-Americans are somewhat more likely to be the victims of fatal bike collisions than whites.

- African Americans and Hispanics were more likely than whites to say biking is a convenient way to get around, and were more likely to bike for pleasure than whites.

- Every demographic group says they would bike more if there were more protected infrastructure

Taken together, these facts tell a story that turns the popular caricature of bike and pedestrian advocacy as a boutique cause for white elites on its head.

How can streets policy become a force for equity then?

The report gives the microphone to several local transportation advocates from Atlanta, California’s Inland Empire, Denver, Queens, Pittsburgh, and some international cities as well to tell their stories and highlight specific projects and policy changes that they’ve championed in their areas.

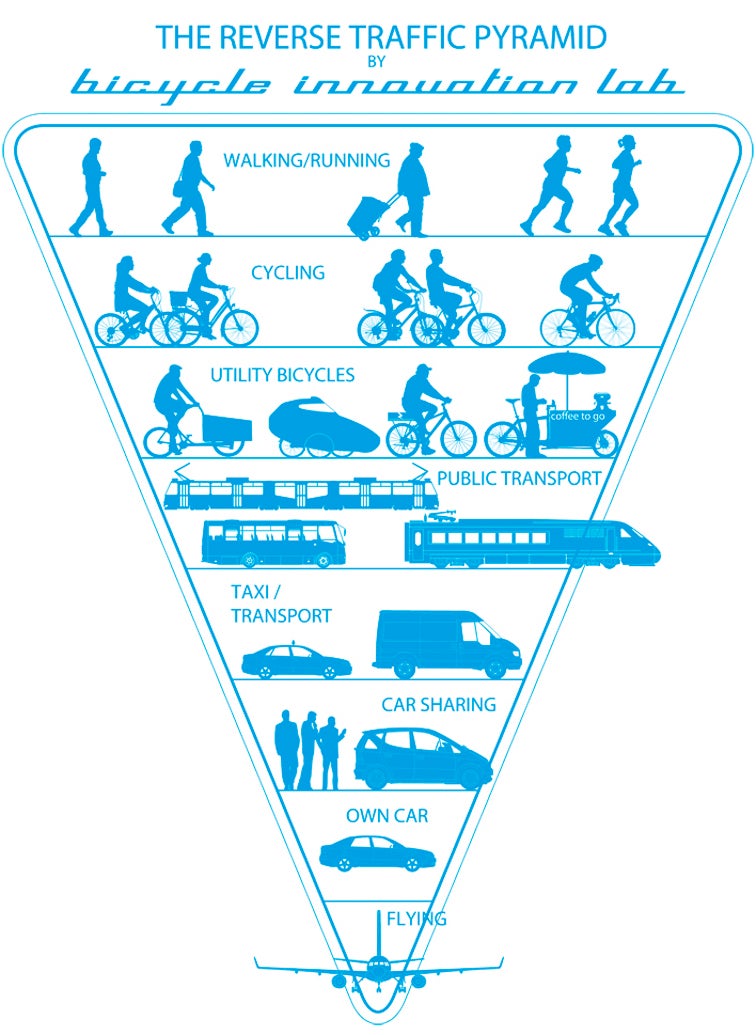

What all the projects had in common is that they redistributed space on the public streets from the most expensive mode of personal transportation (private cars) to cheaper ones (walking, biking, transit) so that the cheapest ways of getting around become the most convenient.

To sample the political logic in its purest form, jump to the section about Bogotá, Colombia.

“[A] pair of young Bogotano politicians began to make an interesting argument: if everyone is equal under the law, then public road space should be distributed to everyone equally.

“A city could find oil or diamonds underground, and it would not be as valuable as road space,” Enrique Penalosa, one of the politicians, explained in 2013. “A bus with 80 passengers has a right to 80 times more road space than a car with one.”

During the decade that Penalosa and his contemporary Antanas Mockus alternated mayoralties, this radical idea—democratizing space—became the basis for two initiatives that transformed Bogotá: the TransMilenio bus rapid transit system and the ciclorutas, a 180-mile network of protected bike lanes that integrate with and feed the bus lines […[

“A citizen on a $30 bicycle,” Penalosa says, “is equally important as one in a $30,000 car.”

Penalosa’s argument starts from the premise that people have an equal right to use of the public right-of-way in the street. From there, it follows that the least space-intensive ways of getting around deserve priority treatment. This image from Bicycle Innovation Lab makes the point even more clearly:

To this way of thinking about equity, people walking or biking take up less space per traveler than any motorized vehicle, so they come first. Bus traffic comes next because a bus carries more people than a passenger vehicle. Taxis carry more people per day than a typical Zipcar, so they take priority. And then lowest of all is the personal car, which for most Americans remains parked 23 hours a day, not carrying very many people at all.

Right-of-way politics in Philadelphia are basically the reverse of this. Space for parked cars is considered to be of paramount importance, and two lanes are occupied by parking wherever it fits (and in many cases where it doesn’t). Meanwhile buses, bikes, and general traffic share one or two lanes on most streets, with even the most popular buses stuck in mixed traffic. Even on corridors that the city and SEPTA have designated as “Transit First” areas (where, by definition, transit is supposed to take priority over general traffic), transit still takes a back seat to general traffic.

For a concrete example, recall that the restored Route 15 trolley was supposed to get transit signal priority (nerd-speak for coordinating traffic lights so as to reduce dwell time for buses and trolleys) enhancements along the whole route, but concerns over general traffic flow won out. Double parking also keeps the line from running on time, but thus far there’s been no political appetite for enforcing the rules of the road. Interestingly, trolleys actually have legal authority to the middle lanes on Girard, but no one enforces that.

DVRPC’s 2007 “Speeding Up SEPTA” report explains the history:

Between January 2002 and February 2003, Transit First improvements were implemented along the Route 15 corridor in conjunction with that route’s conversion from bus service to restored trolley service. The portions of this restoration that fell under the Transit First umbrella were enhanced platform areas, TSP (extended green) functionality on board the restored PCC trolley vehicles, and the replacement of 36 signal control boxes with an interconnected system that would accommodate the vehicles’ signal priority. The total cost of the Route 15 Transit First project was just over $6 million. Notably, an extended portion of the Route 15 project’s core service area (Girard Avenue between 13th and 33rd streets) did not have TSP installed, partly due to concerns about greater impacts on general traffic.

According to both SEPTA and city staff, the chief impediment to maximizing the benefits of the Route 15 project has been frequent right-of-way interference, due both to incidents (such as accidents) and routine use of the trolley lane by general traffic. Unlike buses or trackless trolleys, trolleys cannot change lanes or detour around accidents, double-parked vehicles, or traffic delays. Accordingly, any disruption to the right of way will result in severe delays, often requiring substitution of bus service until the right of way has been cleared. Most of Route 15’s Girard Avenue portion has a median right of way, with a mix of nearside and far-side stops (with near-side stops being more typical). This right of way is legally restricted to trolleys and left-turning vehicles at certain intersections, but it is not physically protected in any way.

The restoration of the Route 15 trolley service was even delayed by a year because the late ward leader Carol Campbell led a political revolt to protect about a dozen illegal parking spaces, and then-City Councilman Michael Nutter didn’t want to push the envelope.

There are signs that the politics are slowly changing, but for the foreseeable future, private cars seem likely to hang on tenaciously to their privileged status at the top of the Pyramid.

The key to winning more supporters (especially among people of color) according to the Building Equity report, lies in acknowledging the usefulness of cars while at the same time rethinking their place in their pecking order.

“Like most other Americans, most people of color see cars as useful, culturally important tools,” they write, “but in interview after interview, the same theme showed up: Cars don’t belong everywhere. They belong in their place.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.