Two rural museums outside Philadelphia partner to present the work of Wharton Esherick

The Brandywine and Wharton Esherick museums — both tucked into the woods 30 miles apart — exhibit the work of the master craftsman, together.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The Wharton Esherick Museum, hiding in a remote wooded area in Chester County near Malvern, Pennsylvania, is a single-artist museum where the famed wood artist and studio craft furniture maker built his own studio and home in a uniquely expressive design.

The Brandywine Museum, about 30 miles away in Delaware County, occupies a former gristmill hugging the bucolic Brandywine Creek. While presenting many kinds of art, it effectively operates as the museum of Andrew Wyeth and his artistic family.

Together, they are collaborating on the first solo museum exhibition of Esherick’s work since 1958. The Esherick Museum sent about 80 works to the Brandywine Museum as “The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick.” Many of the works on view at the Brandywine have not left Esherick’s studio since he died in 1970.

“Everybody calls it a hidden gem, so we’d like to make it a little less hidden,” said Amanda Burdan, Brandywine senior curator. “Just 30 miles away we have another artist who is so closely connected and so contemporary to the Wyeths and yet working in such a different style. It gives a fuller picture of suburban and rural Pennsylvania.”

Next year, “The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick” will go to the Chazen Museum of Art in Madison, Wisconsin, and then the Taft Museum of Art in Cincinnati, Ohio.

The Esherick Museum offers guided tours by appointment only and is only able to accommodate about 5,000 visitors a year. However, the three-city tour is expected to attract about 120,000 visitors.

Esherick and illustrator N.C. Wyeth, the father of Andrew Wyeth, were contemporaries. Their works were sometimes exhibited together, and they were both involved with the Chester County Art Association — Wyeth as a co-founder, Esherick as an early board member — but it is not known if they personally knew each other.

Today, both studios are open to visitors at the Brandywine and Wharton Esherick museums, respectively.

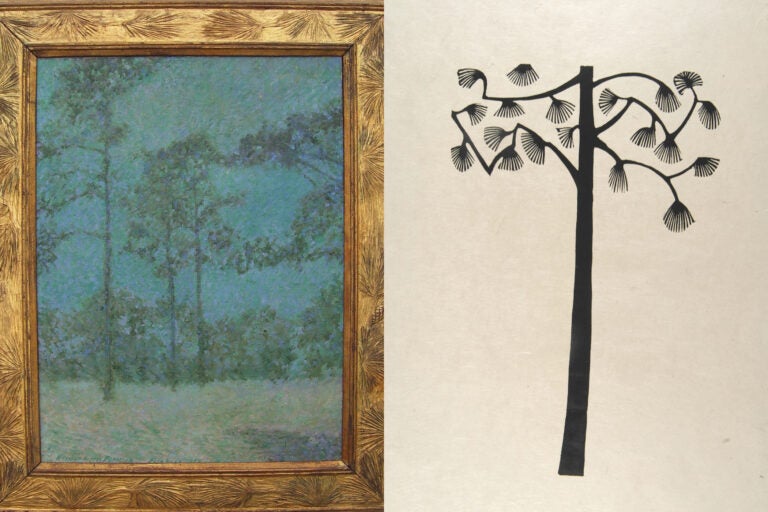

Known as the father of the studio craft movement of the early 20th century, Esherick’s sculptural furniture and architecture elements are notable for their organic curves and expressive abstract decoration. Much of his work has an abhorrence for a straight line and a 90-degree angle, reveling in a sensuous bend wherever possible.

The house and studio he built for himself are no different. Visitors of the WEM are often dazzled by the building itself as much or even more so than the artwork and furnishings inside it.

It has thousands of woodblock prints made by Esherick, but little wall space to hang them. What prints the museum is able to show must compete against the furniture for attention.

Executive Director Julie Siglin said she is appreciating objects she has seen almost daily for the last 11 years in new ways. She pointed to a music stand Esherick made for Herbert and Ethel Koslow, both of whom played flute, crafted from walnut and bent cherry arched like a dancer bending backward. It is presented on a riser in the Brandywine’s white-walled gallery.

“While [curator Emily Zilber] was doing a docent training, I was not paying attention for three full minutes because I’m looking at the double music stand,” she said. “The curvature of the legs on this double music stand really didn’t feel known to me until today.”

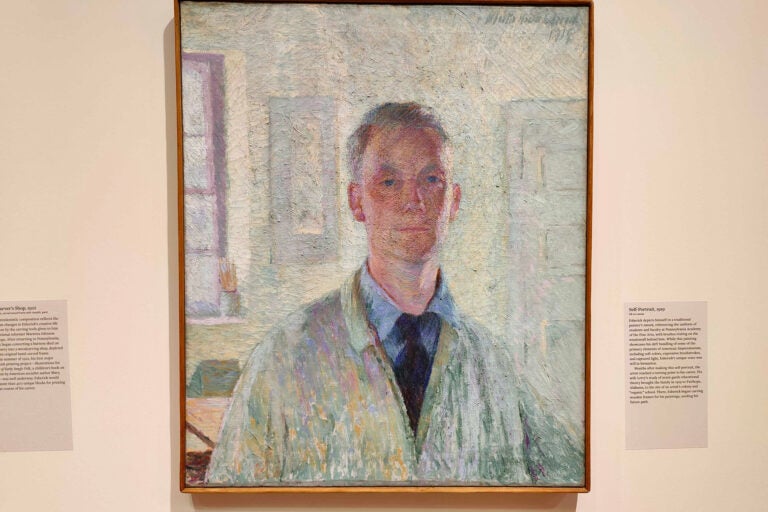

Esherick was born in Philadelphia, where he studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. At age 36, he retreated from the city, moving with his wife Leticia Nofer to a farmhouse near Malvern, where he would later build his studio with a towering concrete silo.

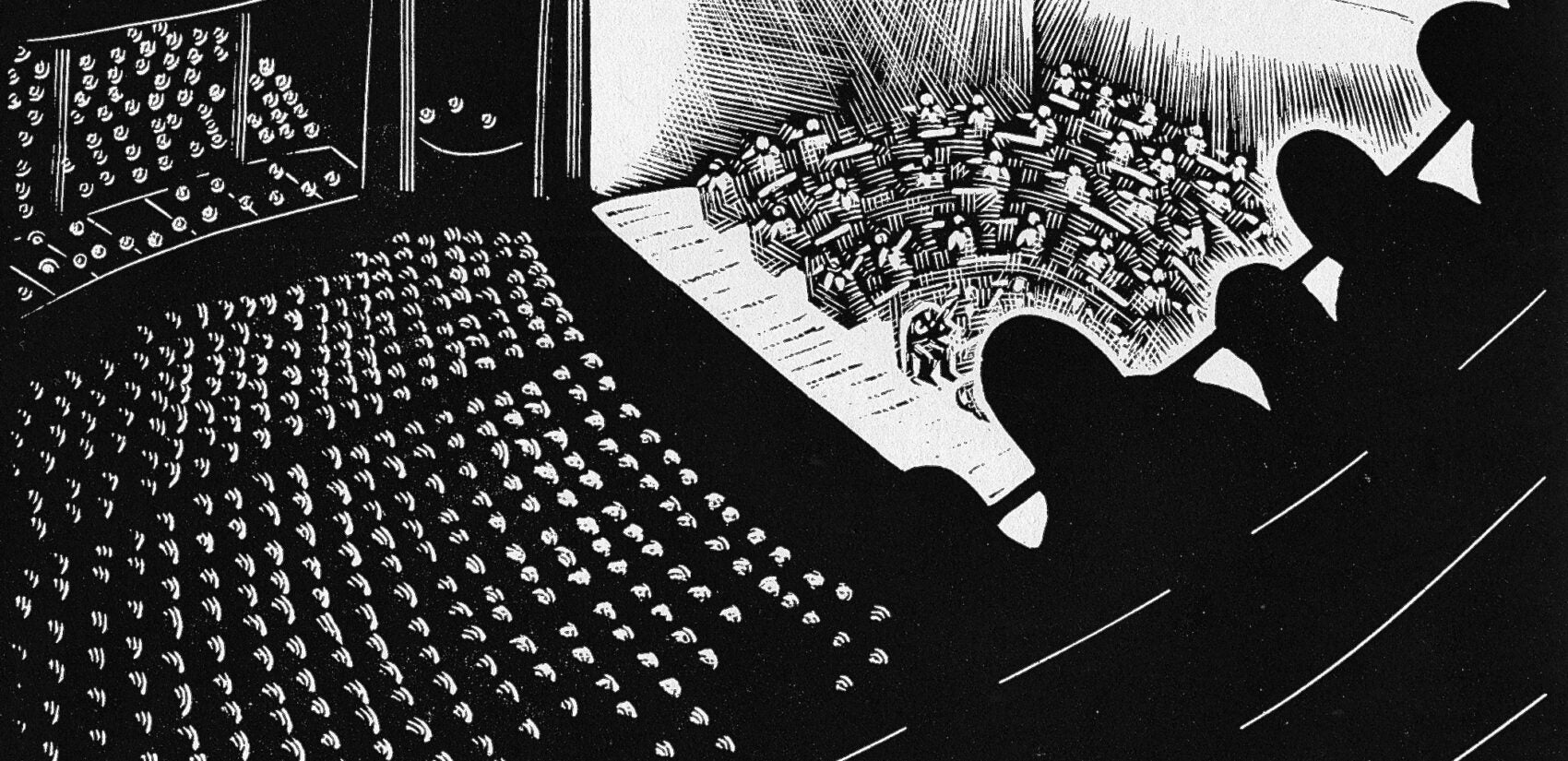

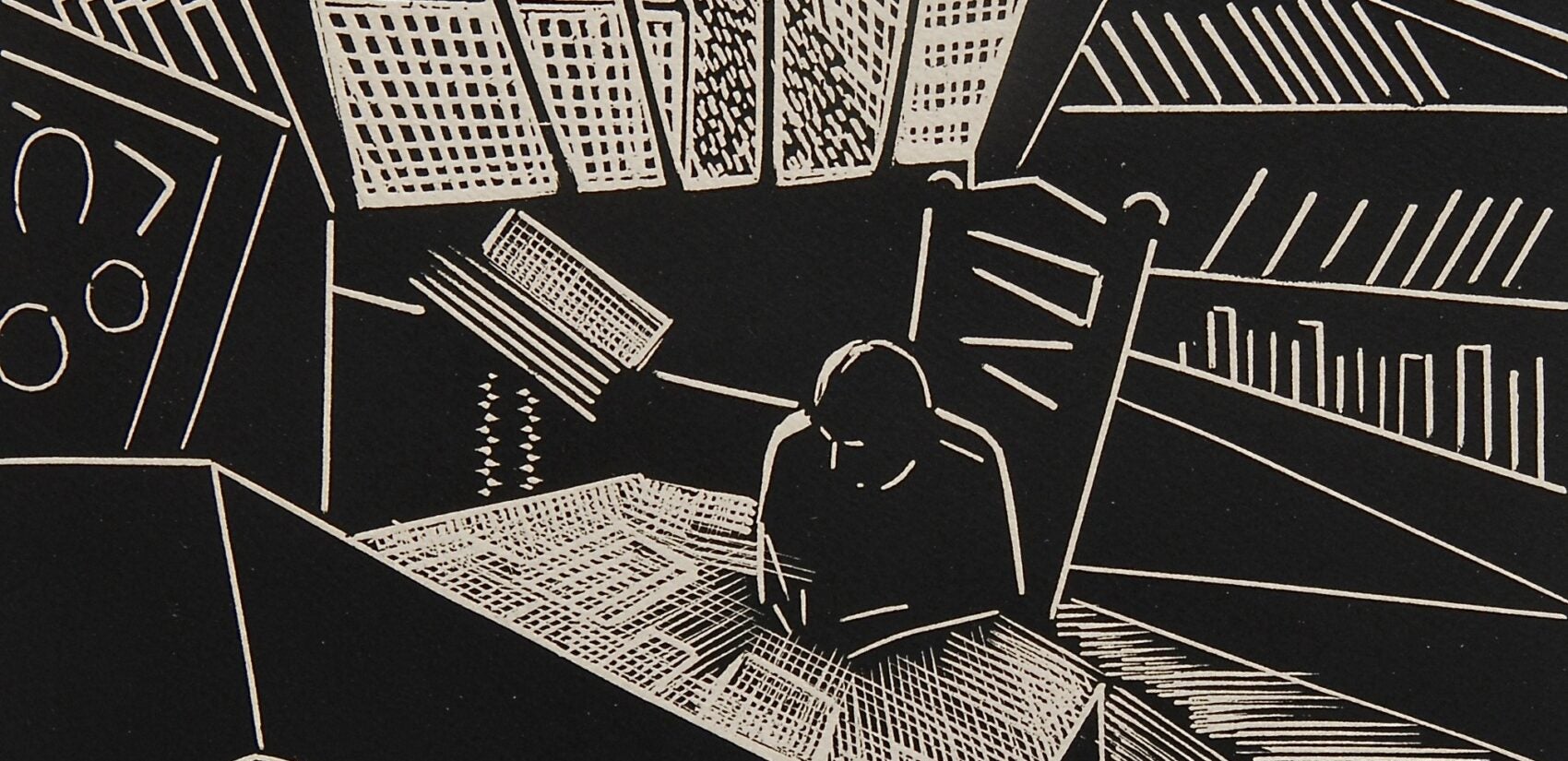

But Esherick did not isolate himself in the woods. “Crafted World” shows the artist engaging in cosmopolitan culture, including “The Concert Meister” (1937), a woodblock print of himself attending a concert of the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Academy of Music; and “Of a Great City” (1928), a woodblock portrait of author Theodore Dreiser in his Manhattan apartment with the New York skyline outside the window.

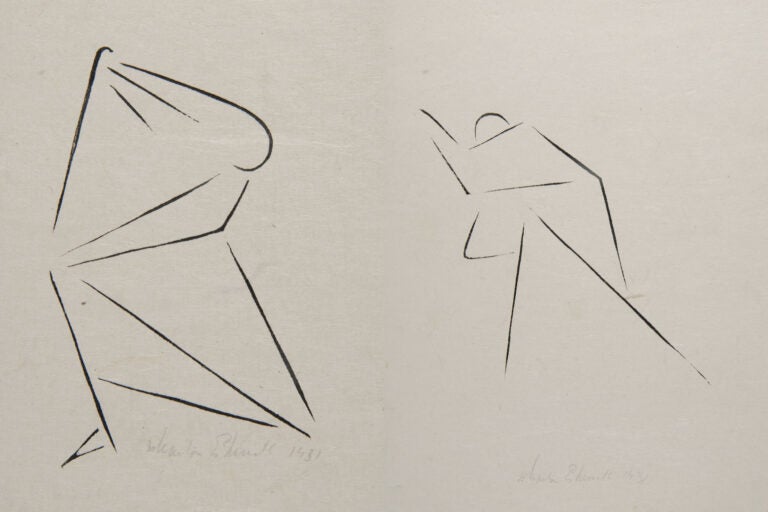

Esherick collaborated widely, such as making furniture and posters for the Hedgerow Theater in Media and illustrating books for Centaur Press in Philadelphia. The figures he designed for the Gardner Doing Dance Camp in the Adirondacks of upstate New York, “Angular Dance” I and II (1931), show Esherick evolving into modernist abstraction: His dancers are almost unrecognizable as figures; instead are sparse lines of gesture and motion.

“He was a master of refinement,” Burdan said. “We talked about this with Andrew Wyeth: You remove and you remove and you remove.”

The Wharton Esherick Museum has a vision of developing its campus to make it more accessible and expand its exhibition spaces, making it able to accommodate more visitors. Siglin said she is in the preliminary phase of designing a capital campaign to actualize that plan.

“The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick” will be on view until Jan. 19.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.