‘We just want to be welcomed back’: The Lenape seek a return home

The legacy of this region’s Indigenous people is all around, in place names and colonial history. Yet the state does not officially acknowledge them.

Listen 4:17

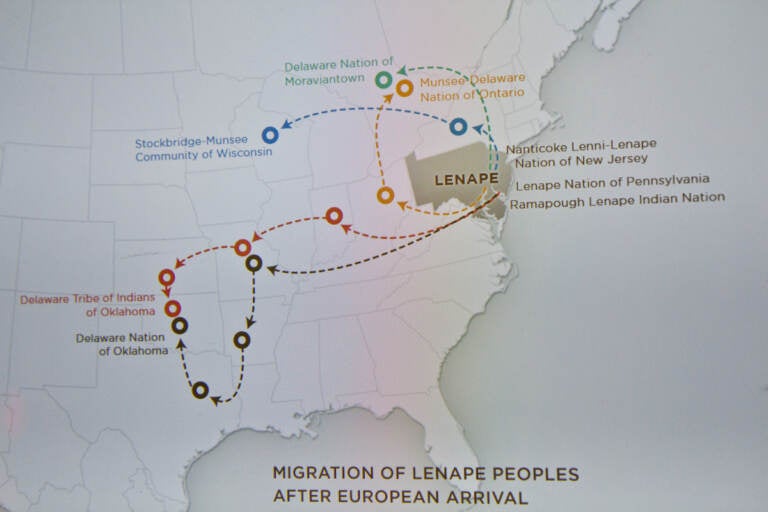

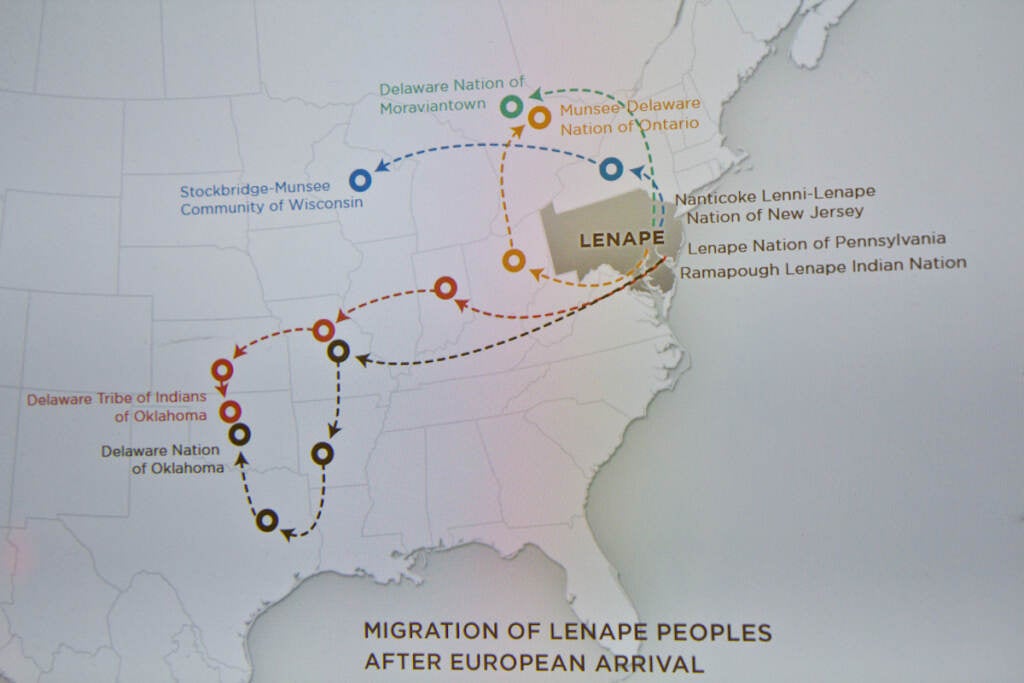

A map at the Penn Museum in Philadelphia shows the forced migration of members of the Lenape Nation. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

We wrote this story based on responses from readers and listeners like you. In Montgomery and Delaware counties, what do you wonder about the places, the people, and the culture that you want WHYY to investigate? Let us know here.

More than 1,000 miles from his ancestral homeland, Curtis Zunigha’s gravelly voice managed to drown out the incessant static of a phone line.

All the way from Bartlesville, Oklahoma, you could hear Zunigha’s passion for the countless stories he carries with him of his people, the Lenape.

“I’m preserving in a dynamic way our culture and our history and our traditions, so that I could pass that on to a younger generation and they can keep going, because that’s our obligation to the creator and to the ancestors, for the gift of our culture and our language and our knowledge of who we were and who we are,” he said.

Zunigha is an enrolled member and cultural director of the Delaware Tribe of Indians, one of three federally recognized tribes of the Lenape in the United States — none of which are currently located in their original homeland.

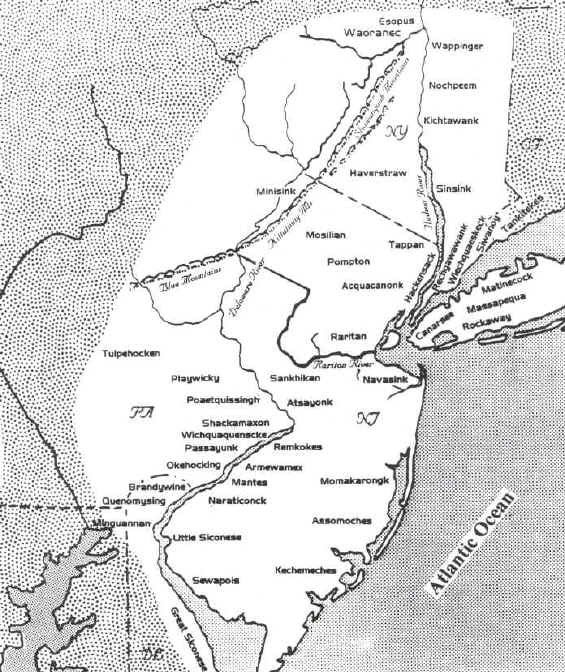

The Lenape, whose name means “the real people,” are indigenous to the Delaware Valley. From parts of New York and eastern Pennsylvania to New Jersey and the coast of Delaware, the Lenape lived in this region for thousands of years. Those relatively newer place names are products of the same colonization that violently uprooted the native people from the area once known as Lenapehoking.

How the Lenape ended up displaced from their homeland was no accident, Zunigha said.

“It is a history of deprivations, of swindles, of murders, of dishonorable behavior by the Dutch, by the British, and later by the Americans. We have been away from our homeland since that time, and yet we have persevered and managed to reorganize and reassemble ourselves,” he said.

A great deal of what is known about the Lenape pre-contact is a combination of written information dating back to the 17th century, oral storytelling, and archaeological record.

“We lived off of the bounty of the forest, the bounty of the rivers, and the bounty of the oceans. And it was a holistic lifestyle, in the sense that all things had a living spirit. And we were given a way of life, to live and balance in harmony with those spirits,” Zunigha said.

He acknowledged that he shouldn’t be sought out as the sole source for extremely detailed historical information, but Zunigha has worked with several institutions, including the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, to help pave a pathway for a Lenape return to the region. His is one of the voices in the museum’s Native American Voices exhibit.

Bill Wierzbowski is the keeper of collections for the American section of the Penn Museum. Over the years, Wierzbowski and Zunigha, and countless others, have formed a relationship that seeks to tell a more complete story of the Lenape.

For example, there are two dialects of the Lenape language.

“The people in the north, so the northern part of New Jersey and into that area of New York, were the Munsee-speaking people, and the people south of that, which included Philadelphia, and New Jersey, were the Unami speakers,” Wierzbowski said.

The languages were mutually intelligible, so speakers of the distinct dialects could still understand one another.

At that time, Lenape communities were only loosely connected, and they moved seasonally, according to Wierzbowski.

“This was a very rich area, in terms of being able to live off of the land, between what was available in the ocean and the rivers and also what was available in the forests [that] allowed the Lenape to have a very, very solid base in subsistence. So, life was good,” Wierzbowski said.

Hunting was done in the fall, and longhouse structures similar to those of the Iroquois people were built in the colder months to keep warm.

“Generally, those structures could have been anywhere up to 100 feet long, about 20 feet wide, and would include maybe six to eight family groupings. But then, with the seasonal change, people would move to river encampments during the summer,” Wierzbowski said.

When the Europeans arrived

First encounters with Europeans came in the 17th century, when the Dutch arrived in the area now known as New York, followed shortly after by the Swedes.

The addition of new groups of people brought tension to the region among neighboring tribes. Eventually, the Iroquois emerged as a prominent political force in the northern parts of New York, and the Lenape became a tributary tribe of the Iroquois.

Meanwhile, farther south, William Penn and other Quaker colonists had arrived in what would become Pennsylvania. But the colonists and the Lenape sought peace, so in 1682 Penn signed the Treaty of Shackamaxon in what is now Penn Treaty Park with Tamanend, a chief of a clan within the Lenape nation.

According to Zunigha, the agreement was to provide land for the Penn colony to take hold.

“Unfortunately, all of those colonial encounters that are in the history books ended tragically in the sense that the Lenape were ultimately run out of this prime land,” he said. “And during a period of over 100 years, many of the Europeans who first showed up and ostensibly were seeking goodwill, trade, commerce and peace and the idea of shared occupancy in the New World, their new world, that ended over a period of time with a series of land theft, swindles, and violent, oftentimes murderous actions by the colonists to run the natives out of their land.”

Zunigha said the colonists’ success in taking the land was largely because of their sheer numbers and firepower. He also pointed to disease that the colonists brought over, which decimated Indigenous populations along the East Coast.

Still, Zunigha acknowledged, the most frustrating part of the Lenape’s loss of land was how a large portion of it came from colonists intentionally misleading them in deals.

“The Lenape, historically, are known as the ones that were in some sort of a fantastic legend, myth out there called the Purchase of Manhattan. And supposedly, we sold the entire island of Manhattan for some trinkets and ax heads … but that is a myth. We did not understand the concept of selling land, having title to land, and those kinds of things,” Zunigha said.

In addition, the Penn family was not immune to “swindling,” according to Zunigha. After the death of William Penn in 1718, his sons, John and Thomas, did a complete 180 in their relationship with the Lenape. Though William Penn would purchase land from the Lenape to sell to colonists, his sons would often sell the land without the consent of the local tribes.

With more and more people coming into the region, the Penn brothers and Provincial Secretary James Logan found it necessary to obtain the upper Delaware and Lehigh River valleys from the native people.

And then came the Walking Purchase of 1737.

The Penn family produced an alleged treaty from 1686 that showed the Lenape had already agreed to sell the land. However, the Lenape claimed that the deal was a fraud.

According to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, “it is very likely that the reason for the Indians’ ignorance of the 1686 sale is that it never happened. Logan could not produce an original copy of the deed, nor does the sale appear in Pennsylvania’s provincial land records.”

Feeling duped, the Lenape refused to leave and sought the help of the Iroquois — to no avail. Eventually, the Lenape agreed to the purchase in 1737. However, the conditions stated that the land that was to be handed over would start near what is now Wrightstown, Bucks County, to as far “as a man could walk in a day and half.”

At the time, that typically would have been considered a fair unit of measurement. But the Penns hired three walkers. Though two were unable to keep up a fast pace, a third managed to make it all the way to what is now the Borough of Jim Thorpe because the Penns had previously hired scouting parties to clear a path.

The Lenape refused to leave, and eventually Pennsylvania colonial officials successfully called on the Iroquois to force them out in 1741.

After Pennsylvania

“There were stops in Pennsylvania on the way out. They’d actually moved to Indiana,” Wierzbowski said. “And after Indiana, they actually moved out a little bit further into Kansas, where there was a reservation. And post-Civil War, actually, groups began to move to what was then called Indian Country, which is now Oklahoma.”

The various battles and skirmishes of the 19th century further splintered the group, according to Zunigha.

In addition to the physical nature of a forced removal, Zunigha described a more psychological sabotage to destroy Lenape culture — the Indian Boarding Schools.

“That was a part of their effort … to, again, to break down their Indian identity, and forbid the speaking of the language, wearing of Indian clothes, long braids, and all of that stuff. All of that was, it was an attempt to get rid of that, and a pretty good success rate at getting rid of all of that, and rebuilding Indian children several generations into the image of little brown-skinned Christian white people. And so today, we are the modern-day vestiges of all of those different experiments over history,” Zunigha said.

The Lenape languages aren’t nearly as widely known as they once were. The Penn Museum estimates that there are fewer than 10 Munsee speakers alive — and no Unami speakers.

The Lenape’s ancient religion has suffered as well. Zunigha estimated that 95% of the Delaware Tribe of Indians practice Christianity. The last known ceremony of a Lenape religion within the tribe was in 1924.

“We’ve lost a lot. We’ve lost a lot of our traditional knowledge, but we’ve not yet lost our culture. Language is a part of that. And we have a very commendable and even robust language website, www.talk-lenape.org,” Zunigha said.

Today, the other two federally recognized Lenape tribes are the Delaware Nation, which also calls Oklahoma home, and the Stockbridge-Munsee Community in Wisconsin.

There also exist three recognized Canadian tribes in Ontario: the Munsee-Delaware Nation, the Moravian of the Thames First Nations, and the Delaware of Six Nations.

Outside of federal recognition, there are four communities that have received state recognition. In Delaware, there is the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware. Meanwhile in New Jersey, the other three are the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation, the Ramapough Lenape Nation, and the Powhatan Renape Nation.

There is one notable exclusion. Despite being a major hub for the Lenape people, Pennsylvania has no federally recognized tribes. In fact, Pennsylvania is one of only a few Eastern states that doesn’t recognize any native tribes — and that’s not because the Lenape have vanished entirely from the area.

Adam Waterbear DePaul is a tribal council member and story keeper for the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania. He currently resides in Brodheadsville, near the Poconos. Without recognition from the State of Pennsylvania, the group has been forced to operate as a nonprofit.

“Lenape history in this area has been incredibly erased, even more so than many other Native American tribes, with us being one of the first-contact nations out here on the East Coast,” DePaul said.

With all the federally recognized tribes in either Oklahoma or Wisconsin, DePaul said it is a popular misconception that the Lenape only exist in places where they have managed to be recognized by the government.

“What very few people realize is that many of us were able to stay here in our Indigenous homelands. And there were a number of reasons that could happen. But one of the main reasons is that colonial men took a liking to taking Lenape wives,” DePaul said.

DePaul added that marrying into colonial families came with extreme caveats, including the complete disavowal of Lenape culture. As a result, many Lenape descendants in Pennsylvania had to practice their culture in hiding.

Unlike many other tribes, however, the culture within this subset of the Lenape was passed down explicitly by word of mouth.

“We were quite successful in that endeavor of hiding, and identifying and passing ourselves off as white. We really did, for all intents and purposes, disappear from the radar. And aside from just that fact, of hiding, another thing that complicates our erasure here is the process of federal recognition,” DePaul said.

Though falling off the radar served its purpose in preserving oral traditions, it proved to be a double-edged sword. It has barred them from joining others in the diaspora with federal recognition, according to DePaul.

“Pennsylvania is the only state in our Indigenous homeland and one of the … minority of states in the country now that has never acknowledged the Native American people. We are trying to change that. We currently have a state recognition committee. I’m actually on the committee, and we are approaching the state right now and hoping that they will agree to acknowledge us,” DePaul said.

Federal recognition is an entirely different matter. The Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania simply doesn’t meet the requirements, DePaul said, but he believes state recognition is a step in the right direction.

In a statement to WHYY News, a spokesperson for Gov. Tom Wolf was noncommittal on whether he would throw his full support behind the possibility of the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania receiving state recognition.

“Gov. Wolf believes that diversity makes our state stronger and that all cultures should be respected and appreciated. The state legislature would need to pass legislation for the commonwealth to officially recognize a tribe, unless it is recognized by the federal government. If such a bill reaches the governor’s desk, he will give it serious consideration,” the spokesperson said.

Keeping the local legacy alive

In its outreach efforts, the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania has been active through several academic institutions in the region. Swarthmore College previously brought in tribe members to host language classes. Haverford and Bryn Mawr colleges have worked with the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania on an exhibit.

“Next year, we have a very large event, probably our biggest event that we do every four years, the Rising Nation River Journey,” DePaul said. “Basically, it’s a three- to four-week journey we take. We paddle out on the Delaware River. And we have treaty signings and hold events with community partners who are interested in acknowledging the Lenape.”

Take a five-minute drive in any direction in the Delaware Valley, and you might catch a glimpse of what was uprooted as a result of colonization — remnants of the land’s original people. All you have to do is pay attention.

Erika Fellman of Telford, a guidance secretary at Central Bucks West High School, sure has. When WHYY News asked its listeners and readers in Montgomery and Delaware counties what they wanted us to explore, Fellman immediately answered the call.

The Wissahickon, Perkiomen, and Pennypack creeks in Montgomery County are just a handful of the many places and landmarks in this region that draw their names from Lenape words. Fellman was well aware of that, but she feels as if it’s not common knowledge.

“It’s something that I feel is really interesting. And I feel like … more people should know about it,” Fellman said.

The last time Zunigha stepped foot into the city of Philadelphia was prior to the coronavirus pandemic. However, he believes that he is a part of a select few tribe members who have found a way home.

When he works with academic institutions to provide insight into exhibits, Zunigha said, he doesn’t do it for the acclaim. He wants the Lenape people to be seen — both in a literal and figurative sense.

“I want these institutions that I’m working with to help make a way for the people to return to their land, and take their rightful place in the community,” he said.

Turning on the television over the past several years, Zunigha said, he knows there is a connection that can be drawn from colonialism’s violent history and the problems facing society today.

“While we can learn lessons from what happened to us in the past, the effects of colonialism, and some of those lessons will inform your listeners now that colonialism brought a great deal of racism, and racism brought white, European, male-centric power and dominion over the lands of the people,” Zunigha said. “And the residual effects of some of that early colonialism are still felt today, when you wonder why people are having huge crowds filling the streets protesting things like police killing Black people in the streets or that kind of stuff.”

He said he wants the Lenape to have a seat at the table of community power once again in the region.

He also believes that the original people of the land may have the answers to climate change and other challenges.

“We know about pandemics before COVID, because we were dealing with smallpox and diphtheria and other kinds of pandemics that were brought to this continent by the Europeans. So we have a long memory, we have traditional knowledge of dealing with these things. And in spite of the better attempts, by some European colonial powers, to get rid of the land, and to wipe them off the face of the earth, it didn’t work.

“We are still here,” Zunigha said. “We have something valuable to bring to the table. We just want to be welcomed back.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.