‘Figure things out’: How Philly experts, scientists say unhoused children can beat the odds and overcome homelessness

A Philadelphia study finds that almost 25% of youth who experience homelessness find a way out, which researchers call resilience.

Listen 4:28

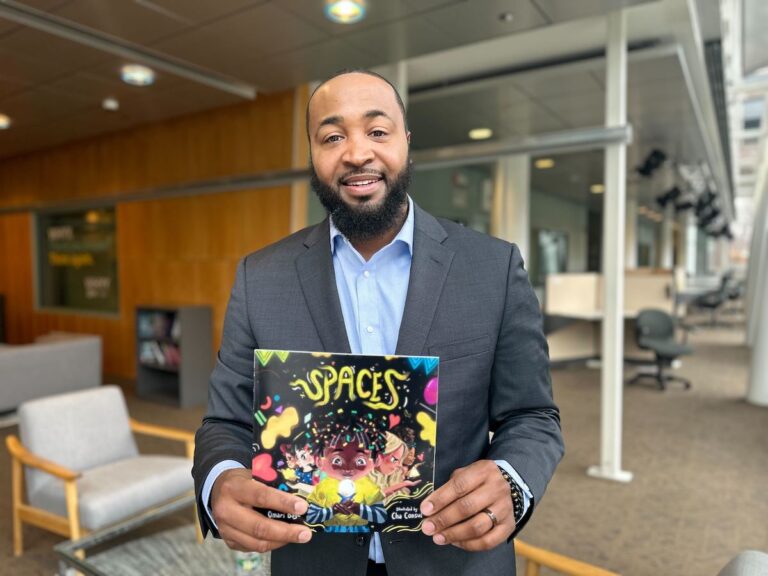

Omari Baye holds a book he authored called “Spaces,” which details the different ways children react to their surroundings, how they overcome and where they find belonging. He said the illustrator used psychology to inform each color and scribble, to represent different moods and childhood experiences.(Vicky Diaz-Camacho/WHYY News)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

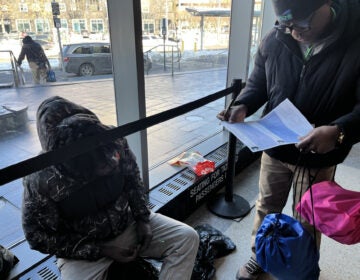

Almost 500 Philadelphia households, adults and children experienced homelessness in 2023.

The figure was determined by the Philadelphia Office of Homeless Services’ latest Point-in-Time count (PIT) taken one night in February 2023. But as housing insecurity and homelessness among children and youth continues to expand, experts are searching for solutions to minimize the traumatic effects over time.

Child development experts, researchers and psychologists in the region like Omari Baye may have found a factor to determine how some youth manage to find their way to stability.

Baye is a psychologist, author and the manager of HopePHL’s Building Early Links to Learning (BELL) Project, which serves children and youth experiencing homelessness. Nemours Children’s Health and HopePHL’s BELL project identified “resiliency” as a tool that could curb poor outcomes for an unhoused child’s future.

Baye has worked in education, homeless shelters and as a family therapist. At each job he says he has observed and seen first-hand what can help children thrive. He described these youths as “nimble.”

“We’re talking about children who have found a way to cope with delayed gratification and figure things out,” Baye said.

“Resilience is really the ability to adapt and not allow yourself to become stuck in place. Because the road isn’t clear, you find a way to clear it. But you also are willing to take a chance on yourself,” he added.

In other words, some children raised in insecure environments find ways to pivot around barriers rather than remaining stuck behind them.

In their research, nearly 25% of youth are considered “resilient” despite the adversity they faced, the BELL study states. Adversity can be defined as “deep poverty” — a family and two children with an annual income of less than $14,000 — or homelessness.

Harvard University’s childhood development department said this function can be built over time.

Harvard used the analogy of a seesaw.

“Protective experiences and coping skills on one side counterbalance significant adversity on the other. Resilience is evident when a child’s health and development tips toward positive outcomes — even when a heavy load of factors is stacked on the negative outcome side,” the report read.

Take earlier interventions, for instance, such as Head Start programs for young children.

Roslyn Edwards, managing director of early childhood programs at HopePHL, believes places like Head Start can serve as a safe space to build children’s coping skills. In her time working with Head Start programs around Philadelphia, she recalls some children calling their teachers “Mommy.”

“For that moment, that early childhood provider is providing that for that kid so that they feel so much love and care,” she said.

Edwards’ career focus has been on early childhood, having worked for federal and local Head Start programs. In her 25 years, she learned that some children thrive despite adverse conditions simply because of the community around them, which becomes a protective barrier.

“It depends on the community that surrounds that child, not so much the conditions but the love of the family and the access that the family [or] the caretaker provides for that child,” she said. “Resilience is such a big word and it’s on a continuum.”

Experts say a stronger network of support across local shelters, agencies and federal organizations will help more children and youth get out of homelessness. BELL’s research is a sort of template of how to implement the strategy more broadly.

J.J. Cutuli, one of the BELL study’s co-authors and a Nemours scientist, agreed.

“There’s many different pathways to and through homelessness,” Cutuli said. “Even within that very strong risk factor of homelessness … resilience is happening.”

Pathways out of homelessness

There are long-term benefits to building resilience.

Unhoused children who are connected with social and emotional support or therapy and education fare better, said professor of child development Anna Masten in an Institute for Education Sciences blog.

Giving more children the tools to build “resilience” could also reduce anxiety, depression or behavioral problems later in life, according to the American Psychological Association. Mental health treatments for childhood trauma decrease risks of adult homelessness, substance use or worsening mental health.

Nurturing resilience among youth experiencing homelessness helps reduce mental health issues and improves their sense of belonging, according to Homeless Hub. It can also reduce traumatic stress, which can have a negative effect on a young person’s ability to cope or regulate their emotions with unexpected life changes as well as their physical health, according to National Health Care for the Homeless Council.

“There is rarely a service that’s truly comprehensive in and of itself,” Nemours scientist Cutuli said. “Children who experience risk, particularly multiple risk factors or multiple adversities, usually need more than one service and more than one agency. … We need to make sure shelter systems’ policies, Health and Human Services systems, know about [childhood] development.”

The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s 2023 report echoed those findings.

And Philadelphia’s at-risk youth are in dire need of these support networks.

Philadelphia County has the second-highest rate of children and youth served by housing programs in Pennsylvania, according to Nemours Children’s Health. Sister Mary Scullion of Project HOME and Office of Homeless Services interim executive director Dave Holloman confirmed that is true in Philadelphia.

Nemours Children’s Health and HopePHL say their plan to triangulate supports should be replicated across the region to help more young people find stability at younger ages.

Having access to a strong community may provide such children an advantage. Studies show that the single most important factor that builds resilience is at least “one stable and committed relationship with a supportive parent, caregiver, or other adult,” according to Harvard.

Some communal living shelters allow children to build their own safe friend groups.

Other strategies focus on transition periods where youth might be most vulnerable, such as high school graduation, said Jordyn Roark at SchoolHouse Connection, a national nonprofit on early care and education for youth experiencing homelessness.

Roark said the most vulnerable times for children are where resources dwindle. This most often happens when a child graduates from high school. SchoolHouse Connection aims to reduce the distress caused by homelessness, whether that be through partnerships with city agencies or college scholarship programs.

The program begins with identifying unhoused high schoolers to support them from the college application process all the way through to college graduation.

“My number one of what I see [is] the make or break of perseverance for the students that persevere the furthest all have the common factor of self-compassion. And that’s nurtured by the caring people in their lives,” Roark said.

“When our young people have access to mental and physical health care, basic needs and a strong and supportive community, they then can often find the space to process their experiences.”

Roark said it is critical that youth feel a continuity of support.

Stories of resilience

Baye, the BELL project manager, recalls one particular family during his time working in the shelter system as a program compliance director.

An 18-year-old with a child and her mom who struggled with substance abuse entered the shelter system. While the grandparent typically becomes a caregiver for the child of a teenage parent, this mom was unable to because of heroin addiction.

So the young mom and her kid were given what Baye called “wraparound supports.” That included case management, child care and help to apply for school aid. Experts say this can change the trajectory for a young person, like it did for the young mom.

“Ultimately she graduated and became a nurse,” Baye said.

This is one example of resilience that leveraged agencies to connect the family to education resources. But, he added, “resilience does not end.”

It ebbs and flows.

Baye says the experience of Jamie Roundtree, 22, is another example.

Roundtree not only experienced homelessness as a family, “flip-flopping from different people’s houses” in West and North Philadelphia, but also on their own as a teen when their family disagreed with their trans identity.

“If I could describe a physical feeling [of being unhoused it] felt like someone putting a cheese grater to my heart,” they added.

Compounding that pain were run-ins with social and case workers who they said discriminated against them and lacked empathy.

“Colorism plays a big part in [it,]” Roundtree said.

Still, as a 10-year-old, Roundtree pulled together resources for themselves and their siblings. Explaining that no place and no person felt welcoming, they wandered from aunts’ homes, to friends’ couches, uprooting from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C. and back to Philadelphia again.

When they were 21, they tapped into networks to get themselves out of unsafe situations, finding support from the LGBTQ+ social services group Pride out of Valley Youth House. After almost 10 years of sleeping on the pavement or anywhere they could find, five months ago they moved into their own apartment.

“I am between acceptance and being numb,” they said. “All I’m really just hoping for is to … keep progressing on this path towards healing. Working on my art, working on myself.”

They are still getting used to the calmness of their new life and home.

“When I close my eyes I still see certain places, I smell certain things. I wish for youth there was like [an] aftercare of some sort … because being houseless is very traumatic.”

“Of course when you’re housed, mentally and physically you’re going to feel better but … that level of vigilance sometimes never leaves,” Roundtree explained. “I’m still just kind of unpacking and trying to heal.”

Ultimately, they want people to have compassion and understand the long-lasting effects instability has on a child in young adulthood.

Their reality now is a new apartment, a job as a barista and a space of their own to make their art.

Baye had a message for Roundtree:

“There’s probably some things that you’re still going to have to process later about the way that they really impacted you but instead of focusing on what’s wrong, you said, ‘How can I create balance? How can I make this right for me?’”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.