Ukrainian refugees in Philly step into the light to have their portraits painted

Dozens of artists at Studio Incamminati painted people displaced by the war in Ukraine. Sale of the portraits will directly support the families.

Listen 1:17

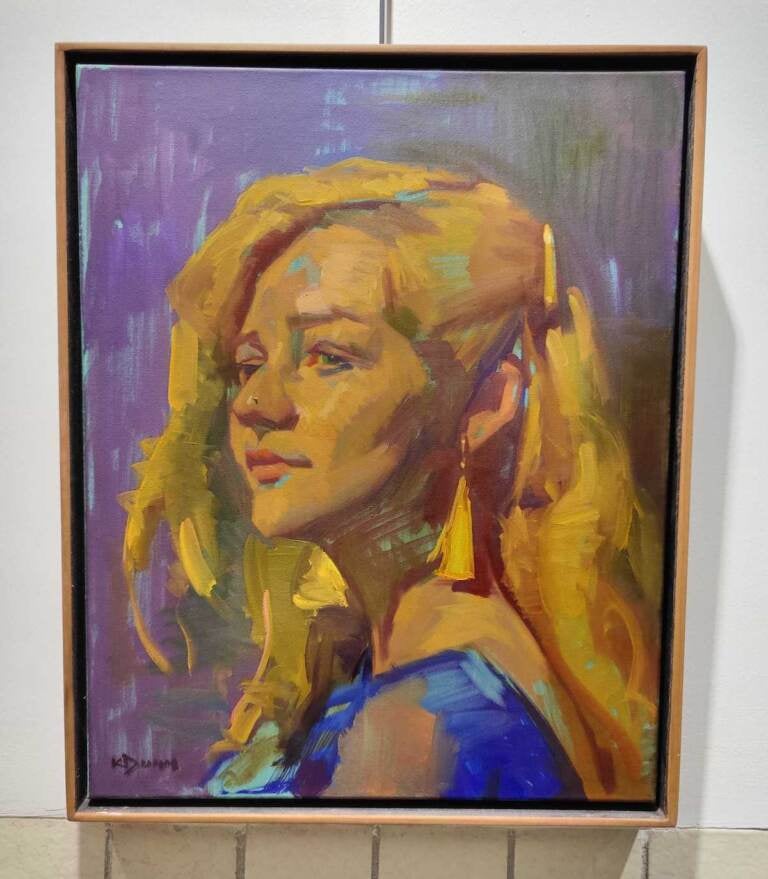

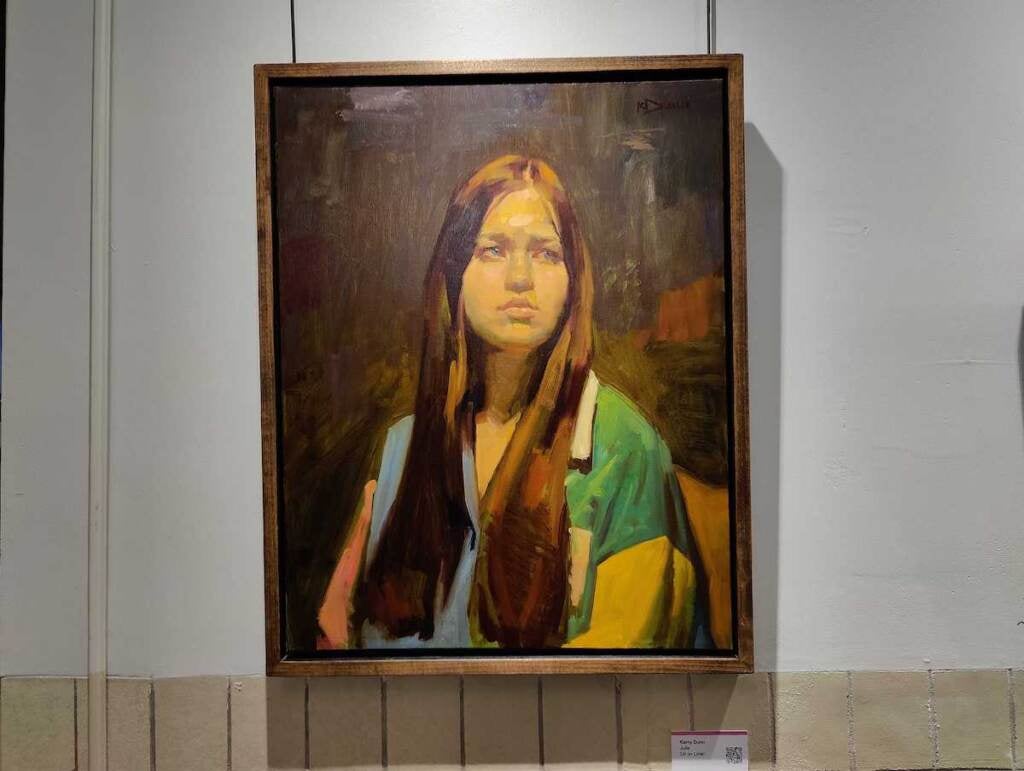

Portrait of Anna Bogdanyk, of Kyiv, painted by Kerry Dunn. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

In February 2022, Slava Levytskyi sent his two children away from Odessa, Ukraine, over concerns that the Russian troops that had been maneuvering nearby would ultimately invade. His fears proved correct.

His daughter Julie, 18, and son Slava Jr., 22, fled with few possessions and arrived in Bucks County. The parents arrived shortly after the invasion began.

Over the last 18 months, the family has been living in Southampton, Pa., trying to fit in. Julie, who missed out on going to prom with her friends in Ukraine, said it’s hard to make new friends here.

“People are so different,” she said. “I do not understand American people at all.”

Julie spoke in a video interview recorded last May at Studio Incamminati, a fine art school in the Bok Building in South Philadelphia, which trains artists in classic figurative portraiture. In May and June, the school invited five Ukrainian families displaced by the war to the school, to have their portraits painted.

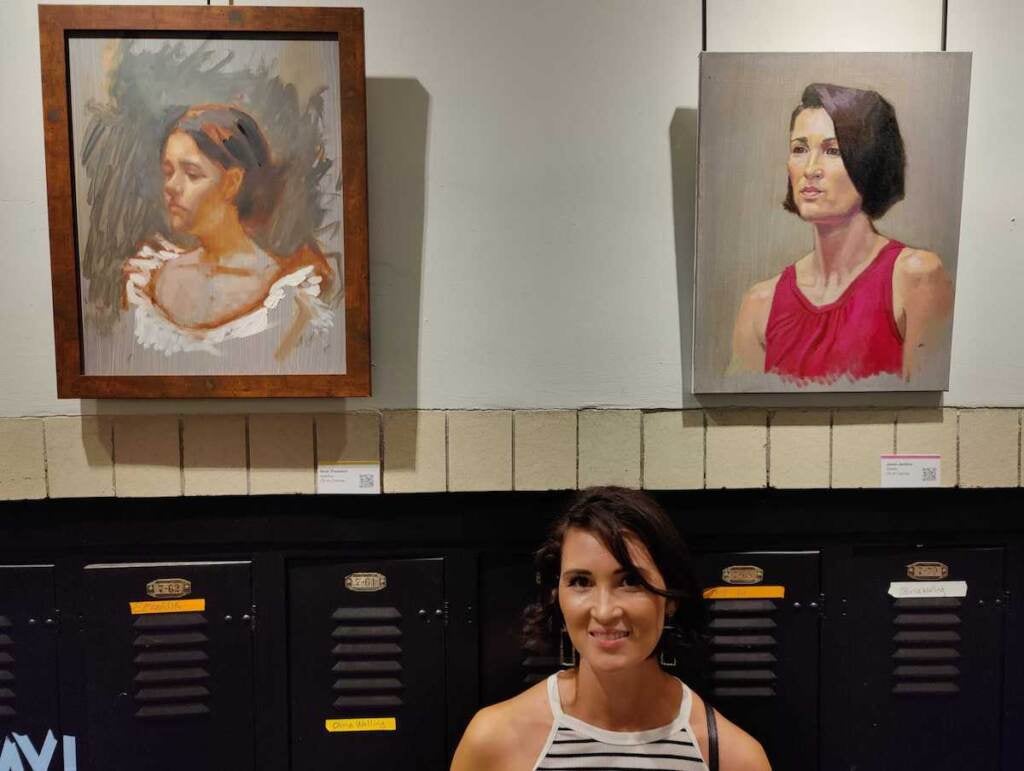

For two days, the Ukrainians came to the seventh floor of the Bok Building to sit for hours at a time (with breaks every 20 minutes) in a series of studios as 40 artists went to work. The resulting portraits — 65 in all — are hung in Studio Incamminati’s long hallway, available for purchase. The Ukrainian families will receive all money from sales.

Called “What We Face,” the portrait project started with Michael Ballezzi, a fourth-year student at Studio Incamminati, and his cousin Meg Burke, who works as a family refugee liaison in Bucks County. Burke learned of five families being supported by the Davisville Church in Southampton, and wanted to raise money for housing, education, and medical costs.

She also wanted to help the Ukrainians acclimate to their new home.

“Michael and I were shocked at how this spread,” Burke said. “We thought we’d get five artists and five families. We had almost 50 different people here. Even people that weren’t being painted came just to watch and be a part of it. It was a collaboration of art that really helped people be seen and heard and tell their stories.”

“It’s a little cliche, but the eyes are a window to the soul,” Ballezzi said. “It’s true for an artist. You’re looking for something to grab onto and capture. If there’s a story behind those eyes then, yeah, it comes out. I think it comes out in the paintings.”

The artists met Anna Bogdanyk, a mother of two and a teacher from Kyiv who visited Pennsylvania in January 2022, not knowing a war would keep her from returning home. She left behind a mother, who ultimately fled to Poland, and a brother who was trapped in Ukraine until a cancer diagnosis allowed him to relocate to Germany for chemotherapy treatment.

She also had to leave behind her dog, Oscar, a golden Yorkie. As soon as a restriction on importing dogs was lifted, Bogdanyk made a trip to Ukraine on a series of planes, trains, and buses through two countries to get into Kyiv and retrieve Oscar.

“I’m crazy,” she said. “I think if we have a pet, it’s like your baby. You can’t live without it.”

Bogdanyk does not plan to go back. She is putting down roots in Pennsylvania with her two passions: She is currently taking classes at Immaculata University to get her pre-K state teaching certificate, and she has already earned a teaching certificate for belly dancing.

“Now I can officially teach this kind of dance, and I also take part in competitions,” said Bogdanyk, who came to the portrait sitting wearing her belly dancing outfit. “I don’t perform in restaurants. I perform mostly in theaters, competitions. It’s my art.”

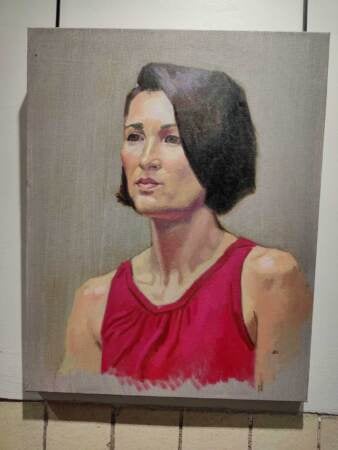

Giselle Minihulova came to Studio Incamminati with her daughter Adelina. Formerly a fitness trainer in Crimea and mother of three children, she was rendered several ways, from a photorealist graphite drawing to oil paintings that captured the vibrancy of her red dress.

“They show my character, my feelings, my passion,” she said. “It’s very cool.”

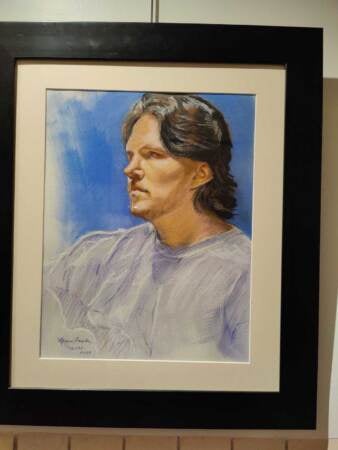

For his portrait, Slava Levytskyi made sure to wear a traditional Ukrainian shirt, a white vyshyvanka with ornate red embroidery. His son, Slava Jr., brought his guitar so he could give the artists music to paint by.

“This guitar became a part of me,” he said. “I wanted to be pictured with something that I see my life with.”

The artists were students, faculty, and professionals associated with Studio Incamminati. Because there were so many interested artists, they were assigned to studios with particular models. They did not get to choose who they painted.

Kerry Dunn, an instructor at Studio Incamminati, was assigned Julie Levytskyi. He was interested in her multi-colored jacket, and her eyes.

“She has this very youthful, innocent quality about her, just turning 18, so I definitely wanted to capture some of that,” he said. “In portrait painting, a lot of it is down to the eyes, down to the mouth, down to the hands. Her eyes, I knew, was going to be the moment if I was going to pull this painting off.”

Julie hesitated at first, believing it would be too awkward to sit in the middle of a room surrounded by strangers staring at her, painting her face. When she returned to Studio Incamminati last week to see the portrait exhibition and reunite with the artists, she said it was worth it.

“My brother convinced me to do this,” she said. “Now I see I’ve got a lot of friends out here. People are being so supportive and so nice.”

Most of the portrait subjects are allowed to be in the United States under the federal United for Ukraine program, wherein dislocated Ukrainians are granted a temporary, two-year parole period. As the war grinds on, that window of time is closing and families will have to figure out what to do next.

The Levytskyi family will likely not be returning to Ukraine anytime soon. Slava Sr. said if and when the Russian invasion ends, the country will still be too dangerous.

“A lot of mines left in our fields. A lot of bombs are left in the seaside, in the fields, in the forests,” he said. “We should stay here because I want to make a safe place for my family.”

As much as she misses Ukraine, Julie is determined to find her way in the states. She said it will be too painful to return to a country that has changed so much, so quickly.

“It’s going to make me really, really upset,” she said. “I want to go there as a tourist. I want to go back to my city, hang out and go to my favorite restaurants and cafes, because I really love the atmosphere and the vibe. I just love Ukraine and I loved the way it made me feel.”

“One day I’ll come back just to feel that life that I used to have.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.