Trains made the Main Line. Why are we designing its future around cars?

The Main Line exists because of the railroad. It’s time we change the zoning code to allow people to take advantage of transit.

The Paoli Local railroad station as seen in an archival photograph.

For the string of communities stretching from Overbook to Malvern, the Paoli/Thorndale Line is an extraordinary asset. Running at speeds of up to 90 mph over Amtrak’s Keystone Corridor, it has a passenger capacity more than twice that of the Schuylkill Expressway. It’s the reason we call this place the Main Line. But despite the region’s railroad roots, the car-centric zoning that surrounds stations means the vast majority of trips here are made by car, reducing this mass transit corridor to a limited service for trips to Philadelphia. This transportation pattern comes with serious consequences. There’s a way we can fix it, but first, we need to understand how we got here.

Most 19th-century railroad suburbs were not built like the Main Line. Satellite towns have always orbited large cities like Philly, but they really came into their own with the advent of the railroad, which allowed quick transport throughout a region. Providing a small-town environment, but keeping big city amenities in reach, dense walkable urban cores filled the walking radii of railroads. Conshohocken and Norristown. Lansdowne and Media. These communities all have average population densities between 7,000 and 10,000 people per square mile. Compact, but not claustrophobic. Compare that to the four census blocks that touch the Wayne train station, with a density of 2,896 per square mile. Why the difference? Large estates occupied most of the land on the Main Line until they were subdivided, starting in the 1930s and continuing through the post-war housing boom. Auto-oriented sprawl was then all the rage, so that’s what got built. But that’s not the whole story. Decades later, cultural preferences and climate concerns have shifted, yet this pattern of development remains frozen in amber, not because of market forces, but rather due to a lattice of zoning laws that prevents densification around stations.

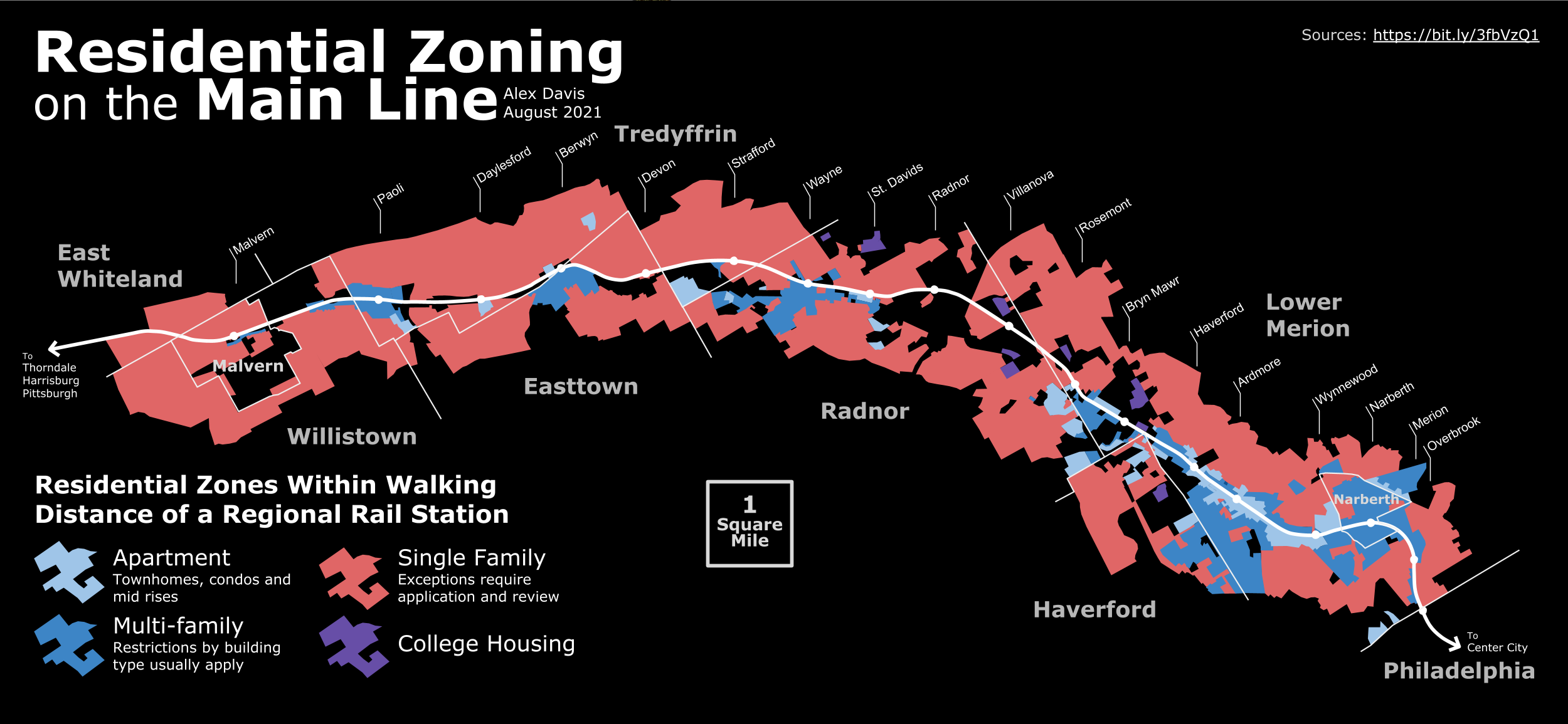

Over the course of two days, I traced zoning maps of the nine municipalities from Overbrook to Malvern to create the map you see above. (If there was an easier way, please don’t tell me.) As you can see, Lower Merion is the only township on this map that is making anywhere near optimal use of the railroad. The islands of multifamily zoning in Paoli, Berwyn, and Wayne might look somewhat reasonable, until you discover that Tredyffrin, Easttown and Radnor all have rules restricting second dwelling units to the upper floor of businesses, leaving all houses effectively limited to use by single families able to shoulder the full cost of the property. And at some stations like Strafford and Devon, the entire station is encased in single-family red.

The problem is that this pattern of development forces people to drive and, even with electric cars, our country cannot continue to cough up the enormous amounts of land, energy, and infrastructure required to support the auto-oriented sprawl that now covers the United States. On top of this, the climate crisis has moved transportation efficiency from a smart economic policy to a global humanitarian imperative. The bad news is that after a lifetime of car-centric planning policies, the United States has the least energy-efficient transportation system of any country in the world.

The Main Line is no exception. Before the pandemic, only 10% of commutes across the nine municipalities were made on transit, and that number has since fallen steeply. And with low frequencies and terrible weekend and evening service, commuting is about the only thing you can do on SEPTA. Every time I stand waiting for SEPTA’s 106 bus, which provides hourly six-day service along Lancaster Ave, I marvel at the relentless river of metal rolling past me. Pre-pandemic, this bus attracted a total of 876 trips on a typical weekday, but daily two-way vehicle counters on Lancaster Avenue usually hit around 22,000. This is at one location, and thus below the actual number of trips along the route, but using it as a conservative proxy, it would mean Lancaster Avenue hosts 35,200 passenger trips if we assume the standard 1.6 passengers per car. That means if just 7.5% of these drivers became riders, the bus would quadruple its ridership and could run every 15 minutes. A couple more percentage points, and SEPTA could justify shelters at every stop. But instead, these people all chose to drive simply because the built landscape was designed for drivers.

The good news is that we don’t need another 70 years to dig ourselves out of this hole. Thanks to our railroad, we are inordinately well suited to retrofit the Main Line into a string of transit-oriented, walkable communities, connected to destinations north and south of the train by frequent bus service. But now that the land has been developed, how do we do it? Do we level Devon in some kind of tyrannical suburban renewal project? Definitely not.

The first target for densification should be large parking lots. In Main Line commercial districts — the black gaps on the map like Wayne and Strafford — almost half of this valuable land is relegated to car storage.

In contrast, the business districts of a more sustainable Main Line would be walkable. And they could be, if this land were occupied by rowhouses or mid-rise buildings. And I’m sure even the business owners, who might be initially opposed to the loss of customer parking, would welcome the new steady supply of customers within walking distance.

Earlier this month, I was thrilled to find out that Lower Merion recently approved a five-story mixed-use building to be constructed on the parking lot next to the IHOP in Ardmore. This is exactly what we need to be doing. Think of it as rezoning for people rather than cars. Instead of mandating space for cars, let’s demand landowners make room for humans.

Would you miss a parking lot?

I grew up in a single-family house 1,000 feet from a train station. (Ironic, I know.) If, hypothetically, my home township of Radnor decided to use eminent domain to knock down my family’s house to build an apartment block, I might even get a little upset. But the question I pose at every block party is: Why aren’t we getting equally upset that we can’t choose to knock down our own houses and build, for instance, an unassuming quadplex. If that’s a bit extreme for you, perhaps you and your next door neighbor might want to build a house in between. If you’re an empty nester, maybe you want to rent out your top floor. If you live near a bus or train station, these are all fantastic ideas. But if you also live in the red area on the map, these non-destructive methods of densification are all made difficult or downright illegal by a litigious litany of zoning restrictions.

Every time a new apartment is planned, I always hear the same set of objections. What I find so maddening is that the vast majority of concerns center around cars. “Tenants will try to park on the street.” “There will be too much traffic.” If these people hate cars so much, then why are they fighting against the very kind of dense housing that would allow people to drive less? If we truly want to solve car-related problems, then let’s build housing that provides people with alternatives to driving.

In 2015, when Villanova University wanted to replace a 6.5-acre parking lot with transit-oriented dorms, I distinctly remember the wave of local opposition on my street. But six years later, I can’t find a single neighbor waxing nostalgic for the days of the giant parking lot, and I saw a noticeable uptick in students on the station platform.

Don’t get me wrong. There are legitimate reasons to oppose construction projects, especially ones located far from transit corridors. But the knee-jerk NIMBYism that repeats itself every time denser housing is planned anywhere is a pattern we have to break. And when we do, there truly is something in it for everyone.

If you’re a business owner, pedestrian patrons won’t leave you for the mall. If you’re a young parent, your children deserve to grow up in a town where they can get around safely without being driven, and develop a sense of independence.

If you’re an environmentalist who wants to save our earth from climate disaster, you can’t do it without getting people out of cars. And if you want to save the last local parcels of forest from the chainsaws, then space-efficient homes are exactly what the housing market needs. If you’re someone who wants to break down the barriers of racial and economic segregation in the Philly region, then you should support legalizing inexpensive apartments on the Main Line that welcome people who can’t afford the expense of driving. If you’re a board member of a local township, borough, or zoning board, and you want your community to be able to survive on a finite earth for decades to come, now is the time to use your position to advocate for change. And to all residents of the Main Line, the next time some townhomes are planned along Lancaster Ave, don’t fight it. Fight for more of it. March to your local planning meeting and demand it.

Leaders will make excuses. But when they tell you that change is impossible, remember this: Before the first Model T rolled off the assembly line, most people weren’t deprived of transportation. Everything they needed on a daily basis was within walking distance and everything else was just a train or trolley ride away. Kids walked to school and played in the street without getting flattened. Few died in car accidents and no one needed to destabilize the earth’s climate just to buy groceries. Today, many other countries are still largely like this. The United States can have this again and the Main Line can do it within a generation. We already have the train. We already have the land. The only thing stopping us is ourselves.

Alex Davis is a local transit advocate and an urban planning student at West Chester University and a graduate of WHYY’s Summer Journalist program.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.