The ‘untold’ revolutionaries: Identity series explores lesser-known Black social movements

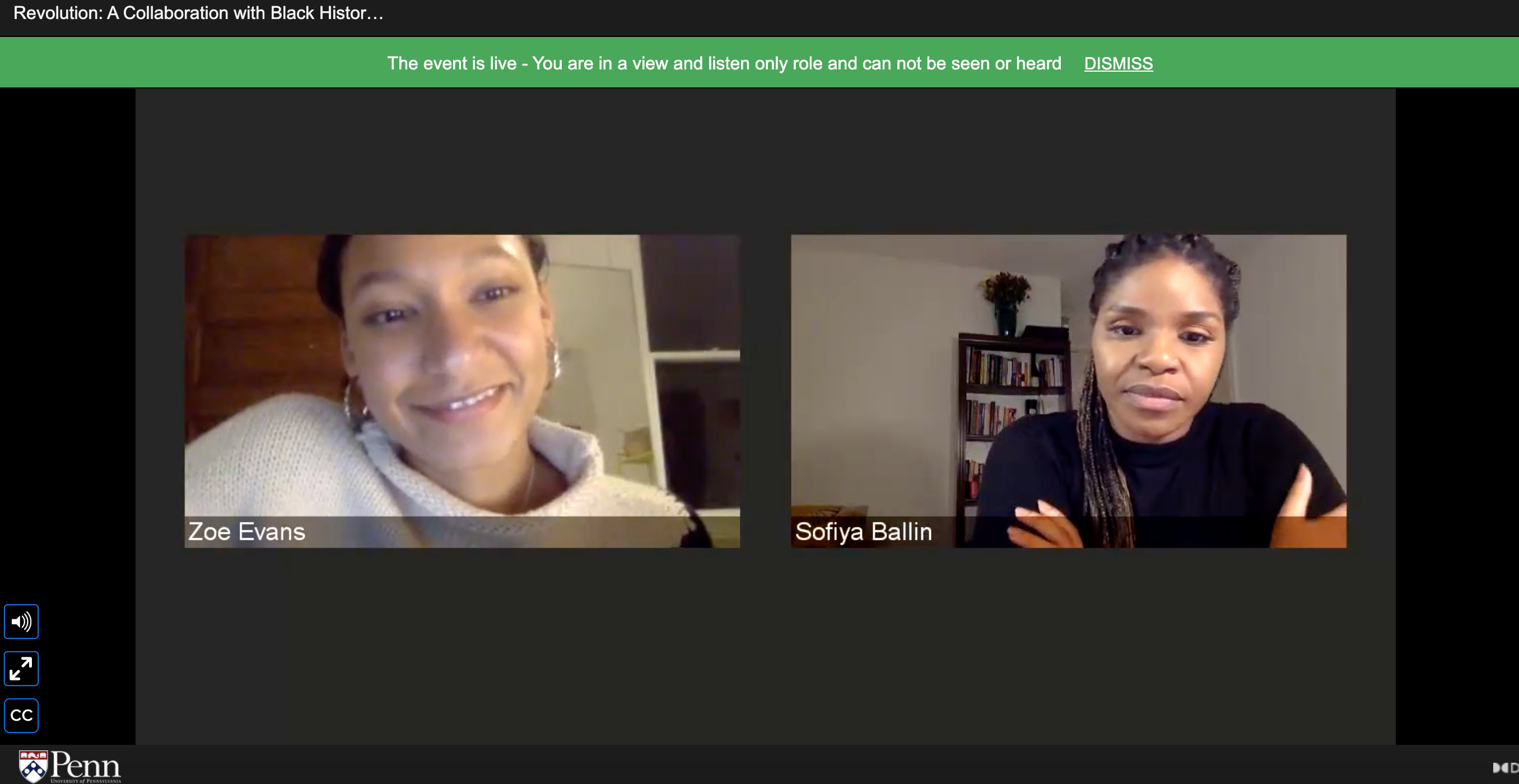

The most recent installment of Philadelphia journalist and storyteller Sofiya Ballin’s Black History Untold series explores the 'untold' histories of Black social movements.

Listen 4:59

In “Revolution," Jamira Burley explores lesser-known Black social movements. (Black History Untold)

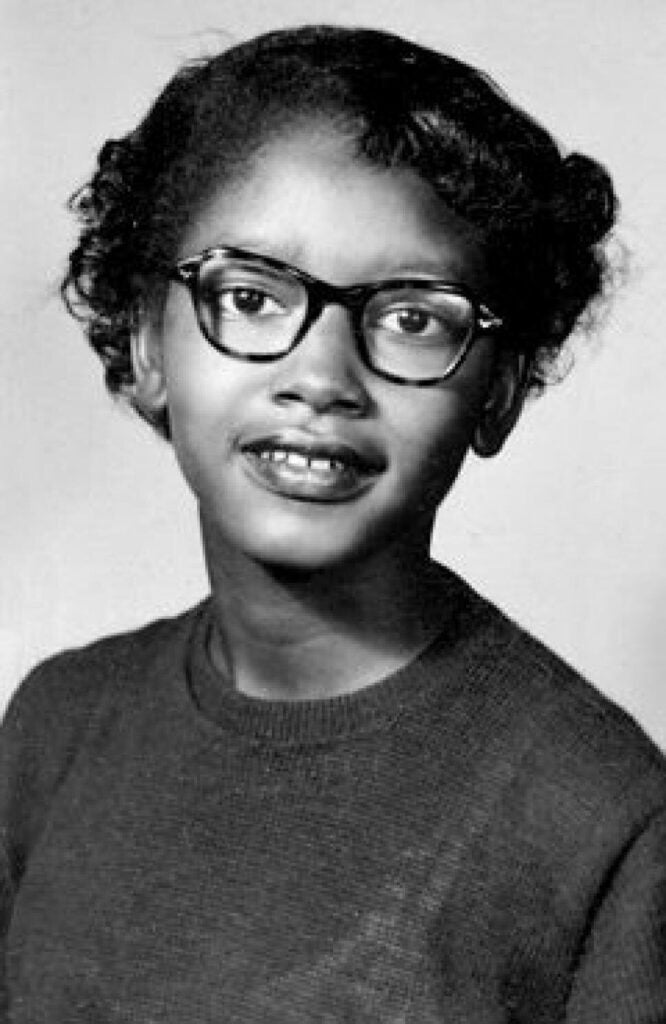

Almost exactly nine months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus — making her historically synonymous with the civil rights’ bus boycott movement — there was Claudette Colvin.

In March 1955, a 15-year-old Colvin was sitting on a completely full bus in Montgomery when the driver asked that she and her schoolmates move so that a white woman could sit there.

The classmates moved, but Colvin did not. She was then arrested, and forcibly removed from the bus by officers and taken to jail.

In the documentary short film “Revolution” — the most recent installment of Philadelphia journalist and storyteller Sofiya Ballin’s Black History Untold series — Jamira Burley discusses why she thinks Colvin’s story is rarely ever heard.

“The story was not elevated until very recently because let’s face it, she was a 15-year-old Black girl from Montgomery, Alabama, who was pregnant during the time of the civil rights movement and people didn’t see her as a perfect activist,” said Burley, a global youth advocate originally from Philadelphia.

In many ways, Burley could see her own story in Colvin’s. When Burley was 15, her brother Andre was shot and killed in Philadelphia. As a young high school student in West Philly, she became a gun violence and criminal justice reform advocate.

“I think as I’ve learned about, and shown up in spaces that were often not meant for me, I’m reminded of Claudette’s story because she reminds me that there’s no age requirement to change the world,” Burley says in the film as archival footage of her speaking in front of a microphone as a teen plays on the screen.

Ballin’s “Revolution” first premiered in February 2020 at a sold-out, in-person screening at the Museum of the American Revolution. One year later, the film screened virtually Wednesday night as part of the Penn Museum’s Black History Month programming.

In creating the film — a new venture from her background as a former reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer — Ballin said she wanted to fight against the inaccurate depiction that Black people throughout history were “docile and meek.”

“People were always plotting how they were going to free themselves, how they were going to fight back,” said Ballin after the virtual screening. “That’s one of the reasons why I really wanted to do this film, to show that we have always loved ourselves enough to do that, and also to inspire people today to do the same.”

Throughout the film, which runs around 30 minutes, you hear stories of Black revolutionaries throughout history, from the role Black women played in the Haitian Revolution, to the stories of Queen Nzinga of 17th-century Angola, and Yaa Asantewaa, the Ashanti queen mother of what’s now Ghana. Each story is told by a Black writer, educator, activist, artist, or poet — from diverse backgrounds both culturally and generationally — who resonated with that lesser-known, yet still influential historical figure.

Ballin said having these vignettes about movements for Black power and uprising throughout history told in such personal ways — rather than by an academic or researcher per se — allowed for the interviewees to take ownership of the stories.

“No one is more qualified to tell Black history than any other Black person,” Ballin said. “As long as it’s accurate, factual, and respectful and not offensive, you are qualified. And I think it’s important to make the work accessible for everyone, that everyone can see a bit of themselves in these interviews.”

Ballin’s identity series started in February 2016 on the pages of the Inquirer as “Black History: What I Wish I Knew,” spotlighting Black Philadelphians on what they learned, or didn’t learn, about Black history.

A child of Jamaican parents, Ballin grew up learning Black history in a global context: the histories of Black people in America, in the Caribbean, and on the continent of Africa.

It instilled pride and a love of Blackness in her, she said.

After first publishing the series, Black History Untold grew in popularity, garnering local and national journalism awards. Then right at the series’ peak in 2017, Ballin decided to take a leap of faith and leave the Inquirer, and pursue the project independently.

Since then, the project has explored different ideas, such as asking Black people to imagine their collective future, or Herstory, bringing the stories of Black women throughout history into the limelight.

Ballin said after screening “Revolution” for the first time last year, those involved in the film could never have anticipated the summer of 2020: a national moment of protest for racial justice after the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery.

The storyteller said over the summer, many people were going back to the film as a source of inspiration and education in what was a tense, difficult time.

“While watching this they were able to breathe and say, ‘We’ve been here before. We’ve been through worse before and we made it through. Here’s how they did it and here’s things we can do differently,’” Ballin said.

On what’s next for Black History Untold, the latest installment “Love,” a film exploring the healing power of Black Love, premieres Feb. 13. Upcoming screenings of that film can be found online.

Penn Museum is also hosting another screening of “Revolution” on Feb. 24, inviting students from Philly and beyond to watch. After the screening, Ballin and others will discuss how to find your voice in predominantly white spaces.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.