The Rizzo reign is finally over. Thank Black Philadelphia.

For more than a decade, African Americans called for the removal of the Rizzo statue. Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney has finally heard them.

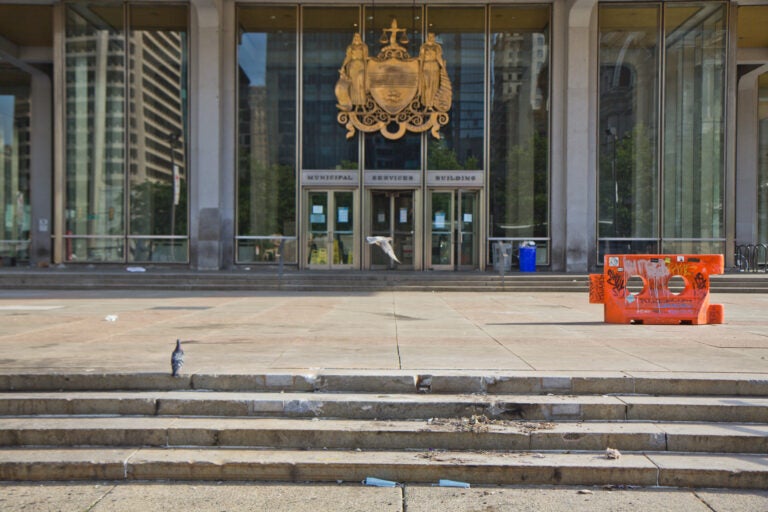

The statue of former Philadelphia mayor and chief of police Frank Rizzo was removed from the city’s Municipal Services Building early Wednesday morning amid civic unrest around the killings of unarmed Black men in the U.S. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

I walked by the Frank Rizzo monument hundreds of times without giving it a second thought. That changed after I began learning about Philadelphia’s jazz history. In the course of researching the lives of the city’s Black musicians, I heard stories about a high school dropout turned police commissioner who harassed jazz musicians and fraternized with Black Mafia nightclub owners on 52nd Street in West Philly, aka “The Strip.” I read about that man — Rizzo — who engaged in a pattern of police brutality that “shocks the conscience,” according to filings related to the U.S. Department of Justice lawsuit.

In Wednesday’s predawn hours, after days of protest, Rizzo’s 2,000-pound bronze likeness was removed from its throne in front of the Municipal Services Building. It should not have taken violent protests for Mayor Kenney to finally remove a statue that “represented bigotry, hatred, and oppression for too many people, for too long.” But as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “The time is always right to do what is right.”

The unceremonious removal came in response to days of protest and years of demands from people like me.

For more than a decade, African Americans called for the removal of the Rizzo statue. Organizations like The Philadelphia Coalition for Racial Economic and Legal Justice mobilized for years to get the statue removed. The calls grew louder in the wake of the protests in Charlottesville, Virginia. The public did not get an opportunity to weigh in on the Rizzo statue until 2017. In collaboration with the Pennsylvania State Chapter of the National Action Network, I hand-delivered to the Office of Arts, Culture and the Creative Economy more than 300 letters calling for the removal of the symbol of hate. In November 2017, Mayor Jim Kenney said the statue would be removed in six months. Nearly three years later, it was still there — until protesters forced Kenney to act.

Philadelphia police knew the statue was a flashpoint, so it was barricaded and guarded by a handful of officers before the Justice for George Floyd Rally began. The police were unprepared to stop the attempts to topple the statue. The demonstrators were whipped into a frenzy that was later unleashed on Walnut and Chestnut streets.

While elected officials asked volunteers to “bring a broom” to clean commercial corridors, the Rizzo statue was cleaned by city employees at the crack of dawn. The prioritization of Rizzo poured salt into the wound. The statue was now protected by a phalanx of security forces. Kevin D. Williamson, a correspondent for the conservative National Review, wrote that it’s the “definition of bad optics.” Williamson called Rizzo “the patron saint of police brutality.”

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

Kenney’s claim that it would take a “month or so” to remove the statue was baseless. After the September 11 terrorist attacks, I volunteered at Ground Zero from October until the last beam was removed in May 2002. The site was cleaned up in nine months.

As we now know, the statue was removed Wednesday in several hours with a small crew of workers.

The Frank Rizzo statue symbolized the worst of Philadelphia — police brutality, racial discrimination and exclusion, cronyism and unaccountability. Its continued presence at the gateway to municipal services undermined efforts to heal our divided and broken city.

Faye M. Anderson is director of All That Philly Jazz, a place-based public history project that is documenting and contextualizing Philadelphia’s golden age of jazz. Faye leads walking tours of Green Book sites in Center City and South Philly. She is included in Generocity’s list of 15 black nonprofit and community voices to listen to in Philadelphia.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.