The ‘beautiful chaos’ of Modern Times at Philly Art Museum

Philadelphia Museum of Art dives deep into its Modernist collection for its 'Modern Times' summer exhibition

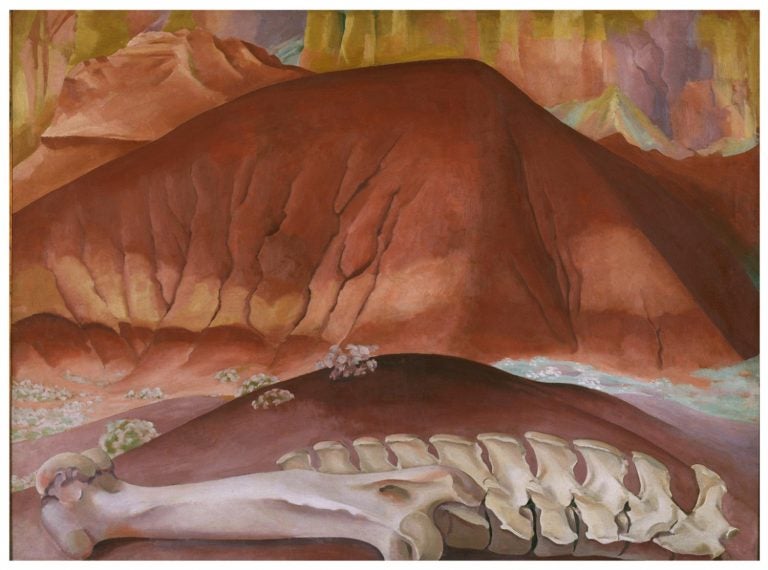

"Red Hills and Bones" (1941) by Georgia O'Keefe; part of the "Modern Times" exhibition at the Philadelphia Art Museum (Provided)

“Modernism” is an almost too-large term that catches many art movements in its 20th-century net — impressionism, cubism, fauvism, expressionism — which didn’t all see eye to eye.

If modernism had a power couple, it might be photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who thrived in his gallery in Manhattan, and his wife, Georgia O’Keeffe, who found inspiration in the deserts of New Mexico.

“There was a moment where people celebrated the machine, celebrated technology and innovation as a completely positive force. Other artists were leery of that,” said Jessica Todd Smith, curator of Modern Times: Modern Art 1910 – 1950.

“There was a group of modernists who really took solace and inspiration in the natural environment and weren’t interested in the geometry of the city,” she said. “Others went the other way, who found cities energizing and exciting places.”

Smith included not just O’Keeffe and Steiglitz, but furniture Wharton Esherick crafted in his secluded forest studio in Malvern. She placed that next to a leather and chrome lounge chair made for the PSFS building in Philadelphia, the first U.S. skyscraper in the International style.

There are also works by John Sloan, an artist trained in Philadelphia who documented street life in New York in sketches and paintings; and Horace Pippin, an untrained African-American artist who painted his life in West Chester, Pennsylvania, in a folk style.

To curate this show, Smith drew entirely from the museum’s deep collection of modern art (including works from a private collection promised to the museum). She selected 156 pieces, much of it falling into pretty standard categories: landscapes, portraits, still lives. But all them evidence an artist kicking against tradition, trying to shuffle off realism in search of something more nuanced.

The narrative of modernism typically draws a straight line from the figurative work of the 19th century to the abstract expressionism of the mid-20th century, where artists were completely untethered from anything recognizable. Smith deliberately selected work with one foot in the real world. Instead of a Jackson Pollock drip painting, for example, she chose his “Male and Female” (1942), which is far from figurative — but at least he left behind clues to the titular characters.

Even works that appear to be straightforward realism — including those of Andrew Wyeth and Edward Hopper — have a deep reservoir of subjectivity that is deliberately buried in the image.

Hopper’s “Road and Trees” (1962) is just what the title says it is, but seems to be more than that.

“Hopper, I find, is an artist who is difficult to talk about because the power of the work is the evocative qualities of the work,” said Smith. “There are questions that the work doesn’t easily answer.”

One of the things that binds all these disparate artists is their ambition to push art into the turmoil of its time, what Smith calls “the beautiful chaos of innovation.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.