Philadelphia health providers and patients seek a new treatment roadmap for sickle cell disease after drug recall

Voxelotor, which was sold under the brand name Oxbryta, was suddenly pulled from the market over safety concerns from clinical trials outside the U.S.

Listen 4:28

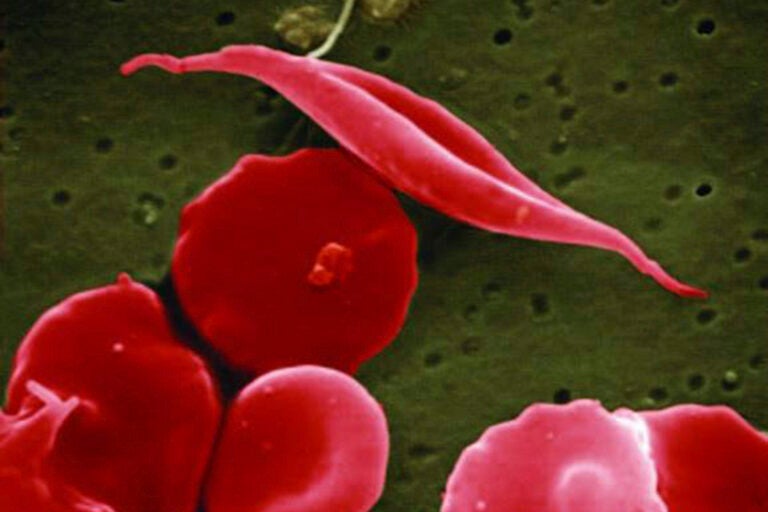

This electron microscope image provided by the National Institutes of Health in 2016 shows a blood cell altered by sickle cell disease, top. (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health via AP)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

About two weeks ago, Ediomi Utuk-Lowery got an unexpected email. It was about a medication called voxelotor, which she has been taking to help manage her sickle cell disease, an inherited blood disorder.

“I read the email, I was like, wait a minute, this can’t be real,” Utuk-Lowery said. “So I Googled it, and then I saw the articles, and I’m just like, no, this cannot be happening.”

The email explained that Pfizer, which manufactured and sold voxelotor under the brand name Oxbryta, voluntarily pulled the medication from shelves over the company’s safety concerns in ongoing clinical trials outside the United States.

The treatment drug has been on the market here since 2019, when it won approval from the Food and Drug Administration. Utuk-Lowery said it’s been working well for her, increasing hemoglobin and oxygen levels in her red blood cells, which makes the recall especially devastating.

“It took a couple days for me to even be able to understand what my doctor was suggesting my weaning protocol should be, because everybody was busy,” she said. “It was a shock to the community. Nobody was prepped.”

Philadelphia health providers and patients say the abrupt move has left them scrambling to find alternative plans for what is a rare disorder that already has few treatment options.

Now, they are banding together as a community to find a new way forward for people living with sickle cell disease, and to increase awareness among the general public about the need for more investment in research and therapies for this disease.

“Our community definitely feels the rub with this one, and it’s so important that we don’t lose the long-term goal of a cure, right?” said Utuk-Lowery, who is also the co-founder of the Crescent Foundation in Philly. “This is the opportunity where you either stay focused or you get off track, and I want our community to stay focused.”

People born with sickle cell inherit the genetic condition from both parents, who either have the disease themselves or carry the genetic trait. There are four subtypes of the disease, each with varying levels of severity and health complications.

An estimated 100,000 people in the U.S. are living with sickle cell, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 90% of patients are Black or of African descent. Other patients are typically from Central and South America, or are of Middle Eastern, Asian, Indian, and Mediterranean descent.

The disease affects red blood cells, which contain the protein hemoglobin, which carries oxygen to the body’s organs and tissue. Sickle cell disease impairs red blood cells’ ability to hold onto oxygen, causing anemia and organ damage. Blood cells can also become rigid and warped into the shape of the letter C, so when they travel through small blood vessels, they can get painfully stuck.

“And this pain, when you talk to patients, is nearly indescribable,” said Dr. Alexis Thompson, chief of the Division of Hematology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “And unfortunately also, even with new treatments, it is still a condition that is associated with a shortened lifespan.”

Stem cell transplants can cure the disease, but the high-risk procedure is performed on few patients and has several short- and long-term health consequences. Newer gene therapies also hold hope for long-term benefits, but they are not yet broadly accessible.

Most treatments for sickle cell manage the everyday complications of the disease, like anemia and pain. Voxelotor was approved because it showed that it could improve hemoglobin and oxygen levels in red blood cells.

It was often prescribed alongside hydroxyurea, a first-line medication used for a majority of patients. Experts say about 5 to 10% of patients in local treatment programs were taking voxelotor, which comes in a daily oral pill.

Following Pfizer’s announcement on Sept. 25 to pull the drug from pharmacy and store shelves, health providers in the area quickly moved to notify patients and families of the change.

“We do not want families to be left with any more uncertainty than they have already,” Thompson said. “We don’t have as much information as we hope to obtain in the coming days to weeks, but the recommendation clearly is to discontinue this medication now.”

There is no exact drug replacement for voxelotor, said Dr. Sophie Lanzkron, director of the Division of Hematology at Thomas Jefferson University’s Sidney Kimmel Medical College. That leaves patients relying on blood transfusions or one of three other medications approved to treat the disease.

Lanzkron said some of these patients have already exhausted those other options in the past, with limited improvements.

“There are some people on voxelotor in which finding an alternative is going to be really, really hard and that breaks my heart,” she said. “Like, what are we going to offer these patients?”

Without an exact roadmap for moving forward after the drug recall, Lanzkron said treatment providers in the area are collaborating to draft action plans and treatment guidance as they seek more answers from Pfizer about voxelotor.

Meanwhile, providers and patient advocates point out that if there were more treatment options to begin with, then people would not struggle so much when one medication leaves the market.

Sickle cell disease was first identified in the early 1900s, but most treatment medications were developed only in the last 30 years.

“I think it speaks to how important this is to do right by our sickle cell community and continue to understand how sickle cell works and what the next best steps are for developing new and innovative therapies that are both safe and effective,” Dr. Scott Peslak, gene therapy lead at Penn Medicine’s Comprehensive Sickle Cell Disease Program and Comprehensive Adult Thalassemia Program.

Peslak said the overall goal is always to keep patients safe while providing care, even if it means recalling a drug that has been on the market for several years now to investigate safety concerns and prevent potential harm.

While many patients may view this as a setback and may be feeling disappointment and anger, Utuk-Lowery said she still has high hopes for the future and encourages people to advocate for themselves and their loved ones living with this disease.

Both she and her sister live with sickle cell disease and have been participating in clinical trials for new treatments since they were kids.

“I think it’s so important to remember that living with sickle cell disease should be a badge of honor. We are heroes, we are warriors,” she said. “So, keep your head up, keep shining. And keep ensuring that you stand up for yourself and your community to the best of your ability.”

Providers advise that patients who are or were taking voxelotor should reach out to their health care providers immediately if they have not already been contacted about the medication’s recall.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.