Russian director reimagines classic Russian play ‘The Cherry Orchard’ for the Wilma Theater

The Wilma Theater brought Dmitry Krymov over from Moscow to direct the classic Russian play “The Cherry Orchard” as the Russian war in Ukraine continues.

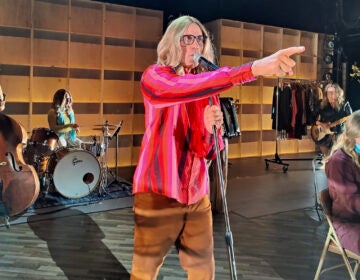

A new volleyball scene is featured in the Wilma Theater's production of Anton Chekhov's famous play, "The Cherry Orchard." (Peter Crimmins/WHYY News)

The Wilma Theater has brought a celebrated experimental theater director from Moscow to reimagine a classic Russian play, “The Cherry Orchard.”

The team departed from Anton Chekhov’s 1903 script about the internal struggles of a formerly wealthy aristocratic family facing the loss of its estate and beloved cherry trees, leaning into the playfulness of the original script’s farce as well as giving an indirect nod to Russia’s current war in Ukraine.

Director Dmitry Krymov and the Wilma had been planning this production for a few years, and Krymov says it is not a response to the fighting in Ukraine.

“I’m not a director who speaks out politically from the stage,” he said backstage at the Wilma, through an interpreter. “I have very specific ideas and I know what I support, but it’s not my style to do political theater.”

Krymov has publicly denounced the Russian invasion of Ukraine by signing a letter alongside other Russian artists, but denies that those convictions informed his approach to Chekhov.

Nevertheless, he praised Chekhov for designing a script with universal human struggles about home and family — about clinging to a glorious but deteriorating past while being blind to an inevitable future — that “The Cherry Orchard” can be interpreted freshly for any age.

“To have this horrible situation that we find ourselves in, and the characters on stage find themselves in a horrible situation. I want the audience and everybody around us to feel compassion,” Krymov said. “When you feel compassion, you attach your feelings towards the people that you are feeling compassion to. All of a sudden you are touched, and you feel their pain.”

“At that point a lot of people think, ‘Oh my God, it’s about me,’” he continued. “That is the most important thing.”

Krymov has said he is uncertain if he will return to Moscow after the play ends in Philadelphia on May 1. Other Russian performance artists have abandoned their country over the war in Ukraine.

Krymov’s production is marked by chaos. Almost immediately in the opening scene a housemaid carrying a bowl of cherries trips and falls center stage, spilling a viscous mess of fruit and cherry juice across the stage. The rest of the scene involves characters comically sliding in the muck while delivering their lines.

Later, the family members attempt to resolve their bickering differences by playing a game of volleyball on stage. An audience member is selected to join them.

Of course, none of this is in the original script. Krymov worked closely with the Wilma’s company of actors — the Hothouse — to develop a play that is inspired by Chekhov, rather than faithful to him. During the development process the actors were free to invent their own lines.

“We had a script supervisor sitting in the theater during the entire rehearsal period,” said managing director Leigh Goldenberg. “They were there capturing exactly what the actors were saying, to then put the script together.”

The actors often break character to address the audience directly. They occasionally shout for lighting and sound cues. Much of the time the stage is lit like a warehouse so audiences can see not just the action on stage but the backstage areas and the props that will be brought out later. The nuts and bolts of dramaturgy are on display.

The production literally puts the play in the audience’s lap: When the family matriarch Madame Ranevskaya arrives at the estate by train from Paris, actress Krista Apple enters from the back of the auditorium. She makes her way to the stage by crossing through the audience, forcing an entire row of seated ticket holders to stand up to let her squeeze past their knees with her travel entourage.

After the Wilma spent much of the last two years experimenting with forms of theater that are digital and distant, Goldenberg says this aggressively in-person production is “theater with a capital T.”

“All the beauty of what makes theater, theater: The aliveness, the needing to be in a space together,” she said. “We knew that if we were still in a digital theatrical space it wasn’t going to work the same way as some of our other work might have translated. It really demands being here in the theater together and relying on all of these surprises.”

That need to be in the same place together is where the play most directly dovetails with the situation in Ukraine. During the volleyball scene, one of the actors, Lindsay Smiling, steps out of character to address the audience directly with a brief, improvised monologue.

He talks about one of the bedrocks of theater: the effect of people sitting together to share a singular experience, inside a safe physical space. Pointing out Krymov seated in front, Smiling explained how people in Ukraine are not as fortunate right now to have such a space.

“It just makes me value this time so much that we can commune together and engage our imagination, so that we know why we’re fighting that other dragon that’s outside,” he said.

That monologue happened during a preview performance of “The Cherry Orchard.” It may or may not happen again — or at least not the same way — during the three-week run of the play. Krymov has designed the production with moments which allow the actors to express themselves as themselves in that moment.

“The Cherry Orchard” runs at the Wilma Theater until May 1.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.